The Democratic Party Is Collapsing. Just Like the Republican Party Did.

And it will all end in tears.

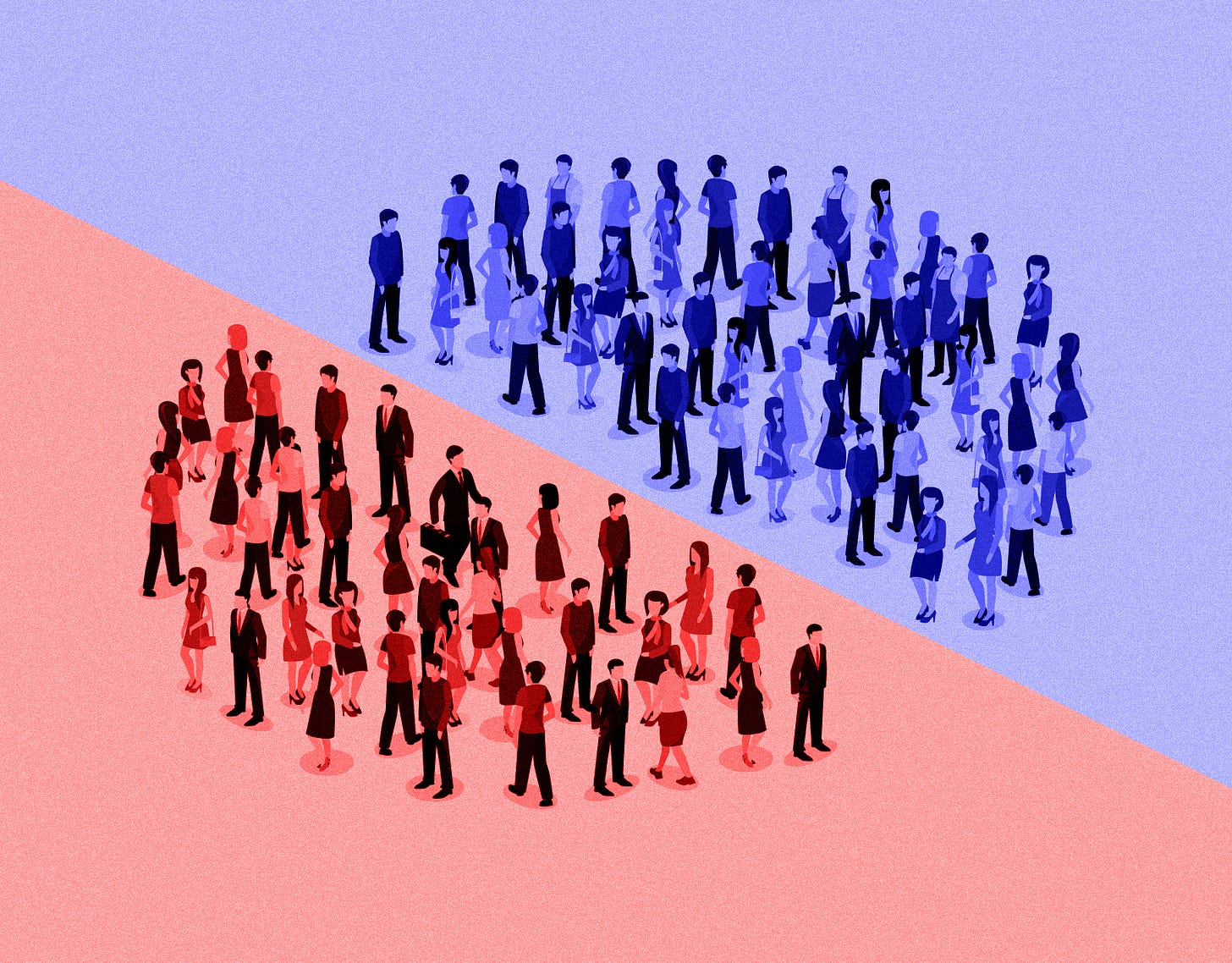

America’s two major political parties have collapsed.

The triumph of Donald Trump in 2016 was a sign of many things, but first and foremost it was a rejection of the Republican party by Republican voters. Democratic voters are poised to perform the same exorcism today using Bernie Sanders as their vehicle.

It is difficult to understate how radical these departures are.

The nomination of Trump in 2016 and the potential nomination of Sanders in 2020 would mean that both political parties turned their backs on their most recent two-term presidents. It would mean a wholesale rejection of everything each party had stood for as recently as a few years ago.

This is not normal.

Ronald Reagan is understood as having transformed the Republican party, but in the summer of 1980, he was actively discussing the possibility of having former president Gerald Ford join his ticket as the vice president. (Ford would go on to speak at the 1988 and 1992 Republican conventions.)

When George H.W. Bush ran for president in 1988, Reagan loomed over the entire affair as a promise to America that Bush would continue his legacy. Indeed, Reagan, H.W. Bush, and Ford remained beloved figures in Republican politics: Every four years the party would genuflect before their images at the national convention.

Once in a while a former nominee or president would hang in the background, or participate only by video, or appear as part of a B-roll package. But even when they skipped the convention, as George W. Bush did in 2012, they weren’t banished. The party embraced every former Republican president and nominee—Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney. Right up until 2016.

In 2016 the only living former Republican presidential nominee willing to support Donald Trump was Dole. And Trump clearly wanted no part of them. Republican voters, asked to take sides in this divorce, threw in their lot with Trump. As a matter of style, ideology, and history, it was a complete rejection of Republicanism as it had existed as recently as eight—or even four—years prior. At a primary debate in South Carolina, Trump suggested he was willing to see George W. Bush impeached for the Iraq war—and Republican voters sided with the Bad Orange Man.

To take it a step further: It is unlikely that any of the three former Republican presidential nominees alive today will ever be welcomed to speak at another Republican National Convention. Because the party has not just moved on from them—it has turned its back.

This state of affairs would merely be an object lesson about the power of demagogues and the fragility of institutions—except that it’s happening again.

Four years ago, Barack Obama was universally beloved by Democrats. He was finishing an eight-year administration that was regarded by the party as hugely successful. There had been no wars; the economy had been steadily improving for nearly the entirety of his term; Obama’s term had been decidedly liberal, if not overtly progressive.

Then Obama’s hand-picked successor, Hillary Clinton, lost the 2016 election. His vice president’s candidacy in the 2020 election is in deep trouble. And the favorite to win the nomination is a democratic-socialist who didn’t even belong to the party until he decided to run against Hillary Clinton and whose campaign is fixed around an explicit rejection of the Obama era.

This is not normal, either.

Take Jimmy Carter. By just about every measure, he was a failed president. Yet the Democratic party never cast him out. Just four years after losing to Reagan, Carter was addressing the DNC from the podium in Chicago. He was welcomed back in 1988 and given a prime-time speaking slot in 1992 even as Bill Clinton was consciously transitioning the party away from Carter’s brand of ’70s liberalism.

Bill Clinton was impeached and disgraced when his vice president, Al Gore, ran for the White House in 2000. Clinton was frustrated that Gore didn’t use him more on the campaign trail, but it wasn’t like the almost-former president was being disavowed: He delivered a major address at the 2000 convention in Los Angeles, to rapturous applause from the crowd. Then he was back at the 2004 convention. And 2008. And 2012. And 2016. Always the belle of the ball.

Historically, the Democrats have been less worshipful of their losers—no one ever asked for Fritz Mondale or Mike Dukakis to come in for curtain calls. But in 2008, John Kerry was up on stage in Denver helping to put Obama over.

And Obama, obviously, did everything he could to help Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Yet here we are, four years later, and Democratic voters are moving toward a candidate who complains that no matter who is elected president, things always stay the same. Who complains about the party on whose ticket he is running. Who promises a “revolution.”

A serious question: If Bernie Sanders is the nominee, will Obama, or the Clintons, or any former Democratic presidential nominee attend the convention and speak on his behalf? Would Sanders even want them to?

After all, Bernie’s revolution is, explicitly, a revolution against them and the Democratic party they built.

Having one political party hijacked by an outsider with no ties to the party—who turns every living presidential nominee into a persona non grata—would be strange.

Having two of them hijacked in that manner would be indicative of something quite important.

Having these hijackings occur over a single four-year period should terrify us.

Political parties are mediating institutions. They temper passions within the electorate because they have entrenched, legacy structures of personnel and tradition and ideology. They are, in a sense, part of the democracy of the dead—one of the mechanisms by which we give over parts of our agency in the present to the vast numbers of people who came before us, won triumphs, made mistakes, and learned lessons.

The story of our age—if I had a nickel for every time I’ve written this—is the failure of our institutions.

But our political parties haven’t just failed. They’ve collapsed. Almost simultaneously.

That’s not good. But what’s really bad is that the parties didn’t just implode and disappear, leaving room for new institutions to flower and replace them.

No.

What has happened is that the parties have become zombie institutions, retaining the support personnel and dumb-pipe logistical power they once had, but without any connection to the traditions and ideologies that once anchored them.

Neither the Republican nor the Democratic party is really even a party anymore. They’re both ghost ships, floating in the fog, waiting for some new pirate to come aboard and take control every four years so that they can use its abandoned cannons to go marauding.

If America were Sweden, none of this would really matter. But we are a country of 330 million souls, with the most dynamic economy on earth and the most disproportionate military advantage humanity has ever seen.

And we are in the process of knowingly destroying the political parties that make governing this leviathan in a responsible manner marginally possible.

The reason we should be terrified—and I wish I had a nickel for this, too—is not because of Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders. They are only symptoms.

All they did was ask their fellow Americans whether or not they’d like to destroy their political institutions. It’s The People who said yes.

The problem is us. Always.