Three Errors About Trump (and An Encouraging Truth)

Plus, why Biden should embrace political heterodoxy and not demand ideological purity.

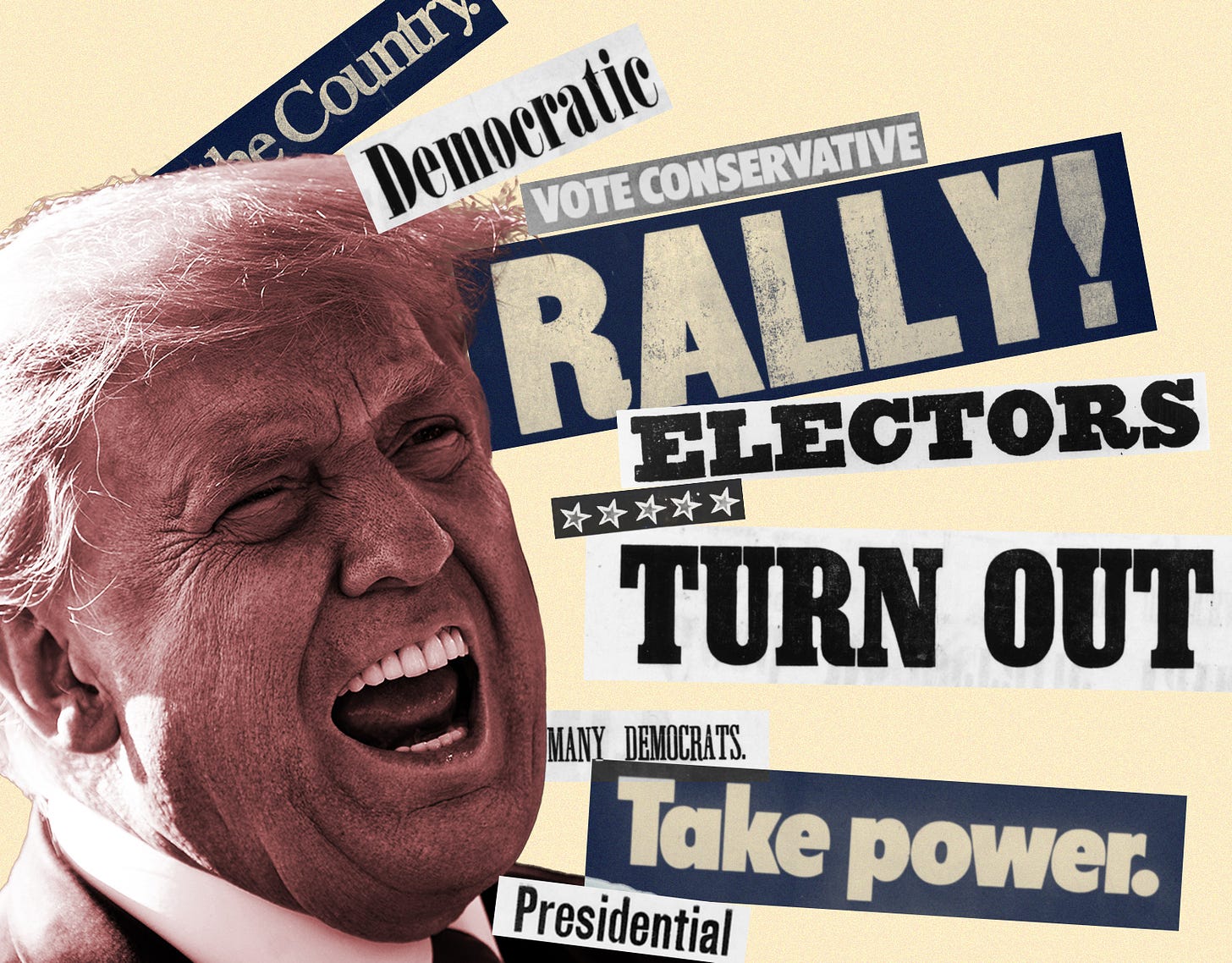

President Trump’s enduring appeal to millions of Americans continues to baffle and bother the learned commentariat, and has given rise to at least three comforting—but flawed—narratives.

First, Trump, we are told, has warped the minds of impressionable voters, brainwashing them into supporting him.

Second, contributing to his success, apparently, is an unprecedented disregard for the truth.

Third, happily, it seems, we can console ourselves in the knowledge that Trump’s effusive exercise of power surely will be the implement of his own undoing, while inevitably tainting and diminishing any results he manages to achieve.

None of this is true.

Trump’s genius, like that of so many other demagogues, isn’t persuasion but perception, his uncanny ability to recognize and amplify the often inchoate views and emotions of others. And shame on those who clutch their pearls and declares themselves shocked by Trump’s abject indifference to facts and truth; Trump’s ability to maliciously contrive and successfully amplify false narratives for electoral gain would impress no one involved with (for example) LBJ’s 1948 Senate campaign. Finally, Trump’s enthusiastic embrace and display of raw power has likely only enhanced both his power and his appeal; it’s a feature, not a bug.

And yet, all is not lost. Our greatest source of hope is our remarkable, glorious heterogeneity, our nuances and our inconsistencies, our stubborn resistance to facile ideological reduction.

Despite the widespread belief—especially in the most refined circles—that “the mass of people” are “hopelessly gullible,” the evidence suggests that actually we “don’t credulously accept whatever we’re told.” So explains cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier in his captivating book Not Born Yesterday. Evolution would have killed us off long ago, Mercier argues, if we didn’t have well-developed “vigilance mechanisms” to critically evaluate new information and carefully assess whether to believe it.

Consequently, he argues, and subsequently demonstrates, “most attempts at mass persuasion . . . from the most banal—advertising, proselytizing—to the most extreme—brainwashing, subliminal influence” turn out to be “miserably unsuccessful.”

Yet demagogues clearly exist, reappearing again and again in history, from Cleon in ancient Greece to Hitler in Nazi Germany. Cleon, a demagogue said to have nearly destroyed Athenian democracy 2,500 years ago, possessed “the true demagogue’s tact of catching the feeling of the people.” As Mercier explains, “By and large, Cleon’s powerful voice reflected, rather than guided, the people’s will.”

Similarly, Hitler’s rise to power and electoral success in 1933 was possible, according to historian Ian Kershaw (cited by Mercier), because Hitler “embodied an already well-established, extensive, ideological consensus”—in particular, anti-Marxism (not anti-Semitism). Early on, Mercier says, “Hitler downplayed his own anti-Semitism, barely mentioning it in public speeches, refusing to sign the appeal for a boycott of Jewish shops.” Hitler “had to preach messages that ran against his [own, anti-Semitic] worldview” and “played on people’s existing opinions”—at first, more consistently anti-Marxist than anti-Semitic.

This pattern is also seen, Mercier argues, in “the long line of American populists, from William Jennings Bryan to Huey Long,” who “relied on the same strategy, gaining political power not by manipulating crowds but my championing opinions that were already popular but not well represented by political leaders.”

Which brings us to Trump. New Yorker writer Evan Osnos recounts a little-known early milestone on Trump’s road to the White House: In 2012, Connecticut businessman and major GOP donor Lee Hanley commissioned pollster Patrick Caddell to “investigate why conventional Republican candidates were underperforming.” The data revealed, in the words of Caddell, that the “level of discontent in this country was beyond anything measurable.”

Hanley discussed these results with several key players in the conservative movement—including Steve Bannon and billionaire Robert Mercer—and identified, as Osnos puts it, an “appetite for a populist challenger who could run as an outsider, exposing corruption and rapacity.” They started to hunt for such a candidate, dubbing the mission “the Candidate Smith project,” after the classic Jimmy Stewart movie, and eventually “concluded that Trump was the closest thing they would find to a Candidate Smith.” Mercer was persuaded to invest in Trump, and the rest, of course, is history.

Trump, in other words, didn’t brainwash a nation of previously content citizens; rather, he was identified as the figure most likely to appeal to this large, and largely underappreciated, group of disaffected Americans—while also presumably willing to play ball with the ultra-affluent of U.S. business and finance.

Trump has been effective at both roles. But he’s also hardly the first American political leader to play them.

When Lyndon Baines Johnson was running for the Senate in 1948, he appeared to be nearing the end of his political career, a journey that had started with brilliant promise, according to Robert Caro’s magisterial, multi-volume biography, when against all expectation Johnson rose from humble roots in the rural Texas Hill Country to become one of the nation’s youngest members of Congress, winning a special election at the age of 28, running as FDR’s most ardent Texas supporter: FDR+LBJ. Yet Johnson had essentially no legislative accomplishments to speak of; he ran for the Senate in 1941 and lost; and after Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Johnson’s influence in the White House diminished to virtually nothing.

Johnson calculated that his last, best chance for political advancement was election to the Senate in 1948. Standing in his way was an almost unimaginably popular figure, Coke Stevenson, a John Wayne-like figure, a self-made, self-sufficient man, the “living personification of frontier individualism” in Caro’s words.

Stevenson had taught himself law and become a highly respected attorney, earning a reputation for civility and fairness. While evincing little interest in politics (he seemed happiest on his ranch), he was eventually persuaded to run for office, first for the Texas House of Representatives, where he was elected in 1929 and elevated to speaker in 1935). He won statewide election for lieutenant governor in 1938, won a special election for governor in 1941 (when the sitting governor, Pappy O’Daniel, decamped for the Senate after defeating Johnson), won a full term as governor in 1942 (taking 69 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary—the only relevant contest in what was effectively a one-party state at the time), and was re-elected in 1944 by an even larger margin, winning the primary in every one of the state’s 254 counties.

Adding to the legend: Stevenson disdained traditional campaigning and preferred to amble from town to town, getting to know the people in an understated fashion.

When Stevenson entered the 1948 Senate race, he was considered the easy favorite, perhaps even a shoo-in; yet when the 81st Congress was sworn in on January 3, 1949, it was Johnson, not Stevenson, taking the oath of office. Johnson would go on to become the Senate majority leader, and ultimately, the 36th president of the United States.

While Caro’s account of the campaign is perhaps best known for revealing how Johnson quite literally stole the election, falsifying votes at the level of individual ballot boxes, the story is also remarkable for revealing how the Johnson campaign closed a seemingly impossible gap, making the final outcome close enough to make the final theft even possible.

Johnson initially attracted attention with a gimmick—a helicopter, dubbed a “flying windmill,” and unfamiliar to most Texans at the time—that attracted curious residents to his rallies and allowed him to campaign efficiently across the expansive, mostly rural state. He also had access to considerable resources, due to close relationships with some deep-pocketed donors invested in Johnson’s continued support of their interests. But even so, he entered the last month of the pivotal campaign significantly behind, and needing to pick up the votes of conservative Democrats—a constituency inclined to support Stevenson, a “symbol of conservatism.”

Johnson was an early adopter of modern polling methods; in 1948, “no politician in Texas had ever used polls as Johnson wanted to use them,” Caro writes. While most politicians might obtain polls monthly, “three or four during a campaign at most,” Johnson wanted polls done weekly, by multiple firms. He wanted not only a more granular understanding of how he was doing, but also a deeper appreciation of the depth of voter preferences, and a better understanding of what issues were important to them.

Explains Caro, in words with a contemporary resonance,

Issues, to Johnson, had never been anything more than campaign fodder; caring about none himself, he had, in every campaign he had run, simply tested, and discarded, one issue after another until he found one which, in his word, “touched”—influenced—voters. (“We didn’t care if the argument was true or not,” recalls one of his college allies. “We just kept trying to find one that touched.”)

Guided by the detailed polling data his money enabled him to acquire, as well as his instinctive understanding of both his audience and his adversary, Johnson hit upon a promising ploy: to falsely assert that Stevenson opposed anti-union legislation that Johnson (like most voters in Texas) strongly supported. Johnson knew Stevenson would likely not deign to dignify the allegation, enabling Johnson to claim Stevenson was dodging the issue.

Johnson persuaded friendly Washington, D.C.-based reporters to challenge Stevenson on this alleged position, and capitalized, as planned, on Stevenson’s initial lack of response.

Johnson’s campaign quickly expanded upon their allegations—wasn’t Stevenson acting like a stooge of the unions? Perhaps, they said, he was even an agent of the Communists. Johnson also employed an army of locals to reinforce this messaging with a seemingly grassroots whisper campaign, tailored to different ethnic groups.

Critical to Johnson’s strategy was the repetition of allegations, through both free and paid media. “Johnson,” writes Caro, “seemed to think he could make Texans—at least rural Texans—swallow even so ridiculous a charge [i.e., the assertion that Stevenson was a Communist] if it was repeated often enough.”

As Johnson’s speechwriter Paul Bolton explained to Caro years later, the idea was simple:

Repeat the same thing over and over and over—jumping on Coke Stevenson’s having secret dealings with labor. You knew it was a damned lie [but] you just repeated it and repeated it and repeated it. Repetition—that was the thing.

Even when the Stevenson campaign finally responded, their response was drowned out by Johnson’s media saturation.

Johnson’s campaign also evolved a strategy of immediately echoing the Stevenson campaign, likely aided by insider access. When Stevenson would use certain language in a speech, Johnson would deliver a speech the same day using nearly identical language, offsetting the impact. And when Stevenson would level an (often accurate) accusation at the Johnson’s campaign, Johnson would immediately direct the same accusation back at Stevenson, a counterpunching style so familiar today.

Caro describes the predictable result:

Who could blame voters, even those who were conscientiously attempting to follow the campaign, for being confused—and, in a sea of identical charges by both candidates, for being convinced by the candidate who could, thanks to the power of money, make the charge so much more frequently than his opponent?

Far too late, Stevenson would recognize that, in Caro’s words:

Johnson’s attacks were working, that Texans were coming to believe that he [Stevenson] was a Communist front, a “do-nothing” Governor who had accomplished nothing for the state, and an opportunistic politician without firm principles or beliefs who would trim his sails to the prevailing wind.

A reasonably apt description, to be sure, though of the wrong candidate.

Johnson’s ability to reframe narratives for political advantage would memorably resurface less than ten years later, when he helped to recast the 1957 launch of Sputnik, which President Eisenhower had downplayed, as the harbinger of a major potential threat. Johnson’s aide George Reedy proposed the strategy in a memo, assuring LBJ that the plan, “if properly followed, would blast the Republicans out of the water, unify the Democratic Party, and elect you President.” Johnson’s opportunistic political maneuvering did much to shape the public’s subsequent understanding of Sputnik as a national security failure; “Sputnik moment” became shorthand for the belated recognition of dangerously overlooked threat.

The example of Johnson is informative in two important ways.

First, in Johnson, we can view a remarkable spectrum of by-now familiar traits: adaptable beliefs, indifference to truth, affection for alternative narratives, and a penchant for reflexive counterpunching—all directed relentlessly toward the acquisition and expansion of power. These are all characteristic of Donald Trump’s political style as well.

And from Johnson—congressional aide, head of the Texas National Youth Administration, representative, senator, majority leader, vice president, and ultimately president—we learn something else about this approach: It can work.

Following his election in 2016, Trump immediately demonstrated his enthusiasm for using the power at his disposal—all of it, whether the privileges of the presidency or the reach of his Twitter—to punish antagonists and reward allies, and to do so conspicuously. It was comforting to assume, as many initially did, that this approach would offer at best only short-term gain, and would ultimately lead to Trump’s undoing. To many, an ever-expanding enemies list and an ever more disgusted public hardly seemed like a recipe for enduring success.

And yet.

The unpleasant truth is that, since embarking on this strategy, Trump’s power has only increased. As Politico’s Tim Alberta recently reported, there is effectively no opposition to Trump within the Republican party—he is the party, and the party is Trump. Meanwhile, public support for Trump has remained remarkably steady; his approval numbers clock in at around 43 percent.

One researcher who is definitely not surprised is Jeffrey Pfeffer, who has spent decades at Stanford studying power and teaching about it. His next book on the subject, he has said, is called The 7 Rules of Power. Notably, he tells me, “Rule 6 is ‘use your power,’ because the more you use it, the more you have.” Rule 7? “Once you are in power, how you got there will be forgotten, forgiven, or both.”

Rule 7, it seems, also informed George H.W. Bush’s decision to run the notorious, Lee Atwater-designed “Willie Horton” ad against Michael Dukakis in 1988 (three years later, a dying Atwater offered a partial apology to Dukakis).

As Bush’s biographer Jon Meacham wrote in the New York Times in 2018, shortly after Bush died,

To serve he had to succeed; to preside he had to prevail. For Mr. Bush the impulses to do in his opponents and to do good were inextricably bound. At the end of the 1988 campaign he mused to himself [in a tape-recorded diary entry], “The country gets over these things fast. I have no apologies, no regrets, and if I had let the press keep defining me as a wimp, a loser, I wouldn’t be where I am today: threatening, close, and who knows, maybe winning.” [Emphasis added.]

At the most basic level, “people want power” explains Pfeffer. “It’s all about self-preservation and being close to power.” This is why “once the Republicans could see that Trump could/would win [in 2016], they came over.”

More interesting, perhaps, is how so many justify their association with the powerful, especially when the object of their affections exhibits seemingly reprehensible traits—such as, say, trashing the appearance of a competitor’s wife, or suggesting the father of the same competitor may have been involved in the Kennedy assassination. Or boasting, on tape, that “when you’re a star . . . you can do anything. . . . Grab ’em by the pussy.”

Americus Reed and colleagues at Wharton, in a classic paper published in 2012, studied this exact question, examining how we “selectively dissociate judgments of morality from judgments of performance,” which, in turn, allows us to “support an immoral actor without being subject to self-reproach.”

Bill Clinton, the authors remind us, was impeached in 1998, admitted to improper conduct, yet “went on to complete his presidency with a 66% approval rating, the highest exit rating since the end of World War II.” Other examples cited include director Roman Polanski receiving an Academy Award after being convicted of statutory rape. Also: Martha Stewart was convicted of insider trading and sentenced to prison in 2004, yet her company’s stock would more than triple in value that year.

As a psychological matter, we primarily manage such conflicts, Reed and colleagues argue, not through rationalization—“construing an immoral action as less immoral”—but rather through what they call “moral decoupling,” allowing us to support morally tarnished products and people by “separating or compartmentalizing the immoral action from the performance of the immoral actor.”

It’s moral decoupling that allows us to separate with surprising ease what our heart tells us we want to do and what our brain may tell us we should do. Moral decoupling allows us to serve both masters, and represents a profoundly underestimated capability that Trump, instinctively, seems to understand and to leverage.

We have arrived at a particularly troubling place. A skilled demagogue has figured out how to channel powerful endogenous emotions that seem to exist beneath the radar of so many political observers. He’s willing to do whatever it takes to win, confident that the ends will justify the means, and will enable him to accrue still more power.

Trump evokes Caro’s description of Johnson, a politician whose “pattern of pragmatism, cynicism and ruthlessness . . . was marked by a lack of any discernible limits. Pragmatism shaded into the morality of the ballot box, a morality in which any maneuver is justified by the end of victory—into a morality that is amorality.”

Yet before we despair, we should remember, as Mercier constantly reminds us, that most people are less gullible and more critical than we tend to believe. In many cases, faith in a particular leader is far less strong than our comments (often voiced strategically, to advance our social aims)—might suggest.

Most demagogues, assures Mercier, hold less sway than we think. Cleon was ridiculed by the playwright Aristophanes, for example, and “when Cleon raised trumped-up charges against Aristophanes,” Mercier reminds us, “a popular jury sided with the playwright.”

Similarly, “Hitler’s appeal waxed and waned with economic and military vicissitudes,” Mercier writes, adding that after the Germans were defeated at Stalingrad, “support for Hitler disintegrated. People stopped seeing him as an inspirational leader, and vicious rumors started to circulate.”

Yet our greatest hope may be our own heterogeneity, the pastiche of views so many of us hold. As political scientist David Shor explained this summer in New York magazine, “there’s a big constellation of issues. The single biggest way that highly educated people who follow politics closely are different from everyone else is that we have much more ideological coherence in our views.”

He continues, “while voters may have more left-wing views than Joe Biden on a few issues, they don’t have the same consistency across their views. There are like tons of pro-life people who want higher taxes, etc.”

Another example Shor cites: “Non-college-educated whites, on average, have very conservative views on immigration, and generally conservative racial attitudes. But they have center-left views on economics; they support universal health care and minimum-wage increases.”

“Moderate” voters, Shor says, citing a famous political science paper from a few years ago, “don’t have moderate views, just ideologically inconsistent ones.” Consequently, “there’s a big mass of voters who agree with us on some issues, and disagree with us on others.”

What emerges, Shor notes, is a “complex optimization problem” that politicians face every time they speak, since “what you say gains you some voters and loses you other voters. But this is actually cool because campaigns have a lot of control over what issues they talk about.”

As important, it also means that even in the age of Trump, the die is not cast, voters are not irreversibly under his control and command, and some of his apparent supporters may ultimately, even now, find greater resonance with Biden. And if Trump starts to lose power, it will likely recede in the familiar pattern: slowly at first, then all at once.

It also means that those hoping to defeat Trump must resist demands for ideological purity, and embrace a more heterodox view. As Mercier tells me, “even (some? most?) Trump supporters hold values that other politicians might better speak to.”

Mercier’s advice echoes a core teaching of business school negotiation classes—try to avoid reductive assumptions about the other party, such as assuming you fully understand their priorities and motivations, and instead seek out opportunities to expand the scope of discussions.

“Adding issues to a negotiation is an important tactic for value creation,” write Harvard Business School professors Deepak Malhotra and Max Bazerman in their 2007 book Negotiation Genius. Why? Because of “a simple formula: more issues=more currency. The more issues you have to play with, the easier it will be to find opportunities” for trade-offs.

Trump may view himself as the Great Negotiator, but Biden, by authentically and persistently searching out opportunities to connect with citizens of diverse views and conflicted loyalties, may ultimately be able to close the deal with the American people.

The key, as Mercier says, is to recognize that “not only does any country contain multitudes, but . . . we all do.”