Living in a Home that Breathes

Windows, box fans, and the complications of technological progress.

My wife and I have been—dejectedly, half-heartedly—shopping for a house in Northern Virginia. I hardly have to explain why it’s not an encouraging endeavor. (If you’re not familiar, just input any locality in Fairfax County into Zillow and filter by “lowest price first.”)

Yet market travails aside, one of the most curious things I’ve noticed during open-house visits around here is that the windows in these expensive, very nice homes frequently do not work.

Sometimes they’re old and have never been replaced; sometimes they’ve been painted shut; some look fine but are so stiff they’ve likely not been opened for years; some are brand new but are so cheap that the plastic in the locking mechanisms warps under pressure so that the window cannot latch shut. Some don’t even have intact screens. (That can sometimes be explained by a realtor trick: Removing the screens lets in more light. In these cases, the screens are stowed in the garage or basement.)

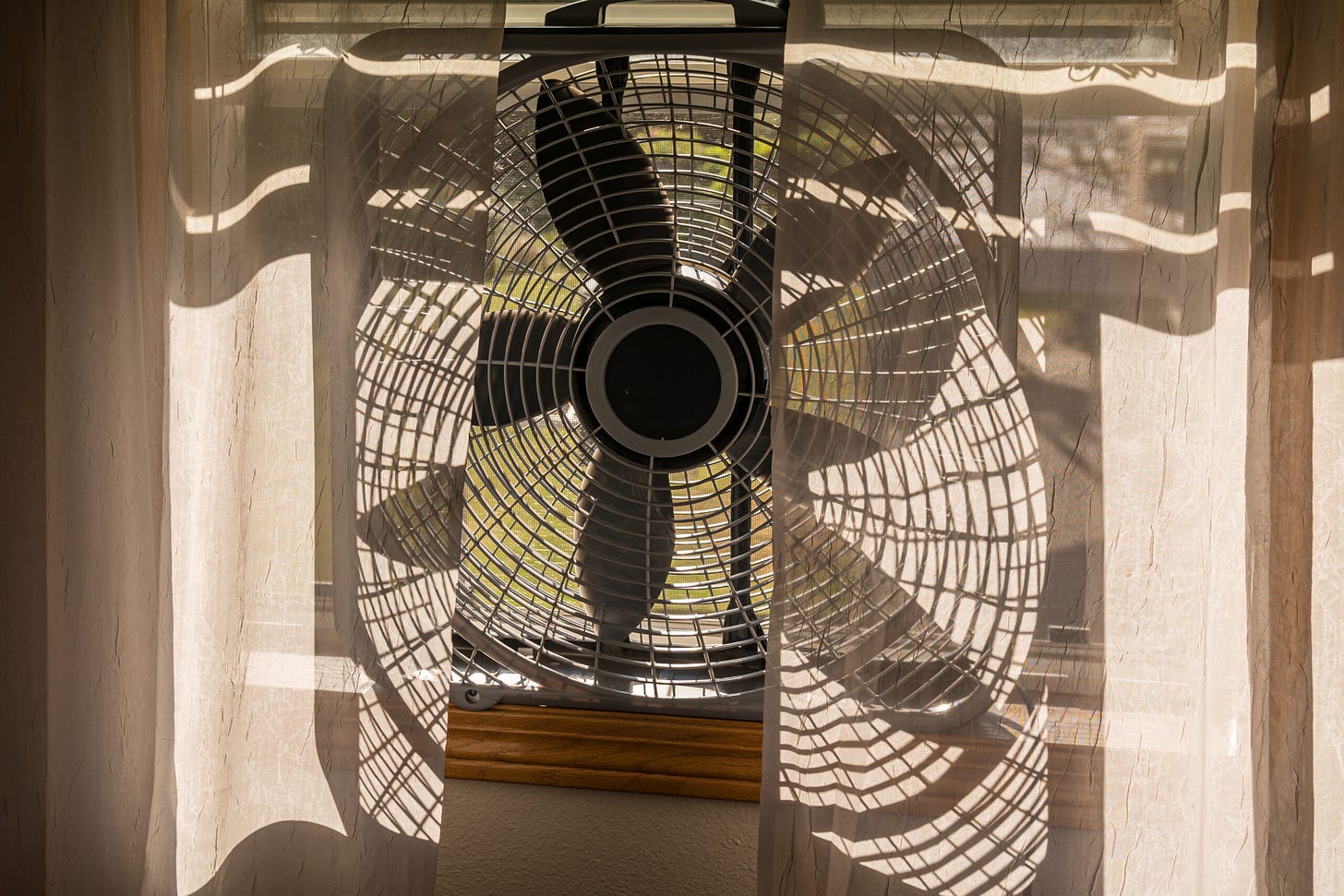

But functional windows are one of the most obvious things to look for in a house, aren’t they? My late-summer plans depend on them: I can’t wait to take advantage of cool nights by getting a box fan running. (Our little condo has sliding windows that don’t accommodate a box fan, which I regret almost as much as the prohibition on barbecue grills.) How can it be that working windows aren’t a priority for affluent homeowners in Northern Virginia? I have to think it’s because they don’t use them: They just flick on the air conditioner instead.

If you’re looking to cool off while saving some energy by using a box fan, you might have to wade through some bad advice before getting a handle on its proper use; the practice is apparently outdated enough to have become foreign to many online. For example, as one site explains,

Box fans operate as any ordinary fan and are helpful for direct purposes, such as drying or cooling off individuals, rather than cooling an entire room.

Window fans operate in pairs, one blowing air in and the other blowing it out. The two fans work to remove the hot air and replace it with cool air.

If placed correctly, window fans can bring the temperature of a room down, while box fans only create a cooling effect.

True as far as it goes, but any experienced box fan user knows that you should open doors and windows to create a cross-breeze and ventilation in concert with the fan. Heck, buy two of them and place them in windows on opposite sides of the home, with one blowing in and one blowing out. Box fans are intended not just for a “cooling effect,” but for recirculating the air. Isn’t that obvious? Maybe not.

Beyond its energy efficiency, cooling a house with fans is, at least for me, the sort of “tactile” or “ritual” activity—like putting on a record, starting a wood fire, or setting an actual alarm clock—that is largely absent from life today. Doing it properly requires being attuned to the weather in a way you don’t need to be with A/C. Is it cool enough to open the windows? Is it too humid? Are the mosquitoes so bad that some fraction of them will get in through the screen? Considerations weighed, you throw the windows open, put the fan up, open doors and other windows to get airflow through the whole space—and you wait. Soon, the house comes to smell like the fresh air outside; the insects, which during cicada season you can probably hear over the fan motor, fill the house with their sounds. It’s almost like you’re out camping, except you're still comfortably ensconced at home.

Because our reliance has shifted to other tools for cooling indoor spaces, current versions of the box fan aren’t manufactured to the robust standards that were common when fans were the best option. It’s easy to look at the flimsy white plastic model sold at Walmart during the summer ($16 when I last checked; maybe it’s $20 now) and wonder how anybody survived the heat before air conditioning. People embraced the easy relief offered by the new home-cooling system when it was introduced, and they gladly threw out, donated, or consigned to garage sales their old box fans, which had lost their primary use case. Many vintage models of the old fans are now rare, collectible, and very expensive as a result.

But as media theorist Marshall McLuhan understood, technological progress has complicated and mixed effects. Even as we gain new conveniences or abilities through new products, we often come to miss the old way. We get rid of yesterday’s tech when it becomes obsolete, but we want it back when it takes on that aura of antiqueness, becomes a historical curiosity, or even starts to convey intimations of forgotten wisdom. Consider things like surviving typewriters, cathode-ray tube televisions, and mechanical push mowers. Of course, nobody would have viewed these recently outdated things in such a rich way just as they were going out of fashion, and so there’s always something anachronistic about this way of assessing them. It might even represent its own kind of boutique consumerism. And it’s easy to romanticize a more difficult past from a comfortable present; innovation is good, and, given the option, most people outside small communities of enthusiasts would prefer not to return to these products over their successors.

But, sentimental projections aside, here’s how cooling the house worked in the heyday of electric fans. Growing up, my father had a General Electric all-metal, three-speed, electrically reversible box fan; it could change directions with the turn of a knob, and could turn a hallway in his childhood house into a wind tunnel. Today that GE fan would be worth over $200. My grandmother gave it away years ago when a nosy handyman working on her HVAC asked if he could have it. That’s more or less what everyone did with them.

But if you compare that fan to the current models, today’s fans look perfunctory, if not vestigial. The sharply angled steel blades of the classic model have become almost flat, thin plastic. These cheap blades produce less airflow, which can be generated by a much cheaper, lighter-weight motor, which in turn allows a thinner, flimsier frame. If you put my dad’s GE fan and the $16 Walmart fan side by side, the difference in size and heft would be astonishing.

Today’s box fans are a commercial afterthought, purchased as backups for a day when the air conditioning breaks down, or for use in old-fashioned college dorms that never got central air. Many sliding windows, like my own, can’t even physically accommodate a box fan, and the window fans they might be able to hold are similarly shrunken and lightweight compared to their predecessors.

What’s interesting in this is the way progress—and there’s no need to put it in scare quotes; air conditioning really does represent an important step forward—can end up disadvantaging the people most in need, putting them in a relatively worse position vis-a-vis everyone else. When widespread computer ownership and high-speed internet access make remote schooling feasible, it’s the people without reliable or recent computers, or without high-speed access, who suffer. When land use becomes oriented around the car, anyone who can’t afford a car is left stranded. And when the widespread adoption of air conditioning kills the profit in heavy, high-performance box fans, it’s the people stuck in buildings with broken or poorly-performing air conditioning systems who are forced to rely on the diminished fans that are still produced. Being at the mercy of a teacher in the classroom, or your own two feet, or the weather, has a natural leveling effect. By obviating these conditions for a few, technological progress can increase inequality for those who are stuck with them.

Now you’d be right to point out that poor families in the 1950s or 1960s weren’t sitting in the breeze of an electrically reversible top-of-the-line GE. More likely, they had a smaller fan, or a lesser name-brand, or a discount model from K-Mart or Sears. But even those units were designed with metal blades and heavy motors. They moved air in large volumes because they had to.

These days, I’m not opening my window and firing up my fan out of solidarity with those who don’t have better options. Some days this summer, I’ve practically gotten on my knees and thanked the Lord for air conditioning. But the vaguely counter-cultural allure of the good old-fashioned box fan calls out to me—as does the lower cooling bill, the freshly scented breeze, the pulsing late-summer trills of the insects, and seeing out the season by letting a little bit of the world in.