A Practice of Thankfulness

The virtue of making a habit of counting your blessings.

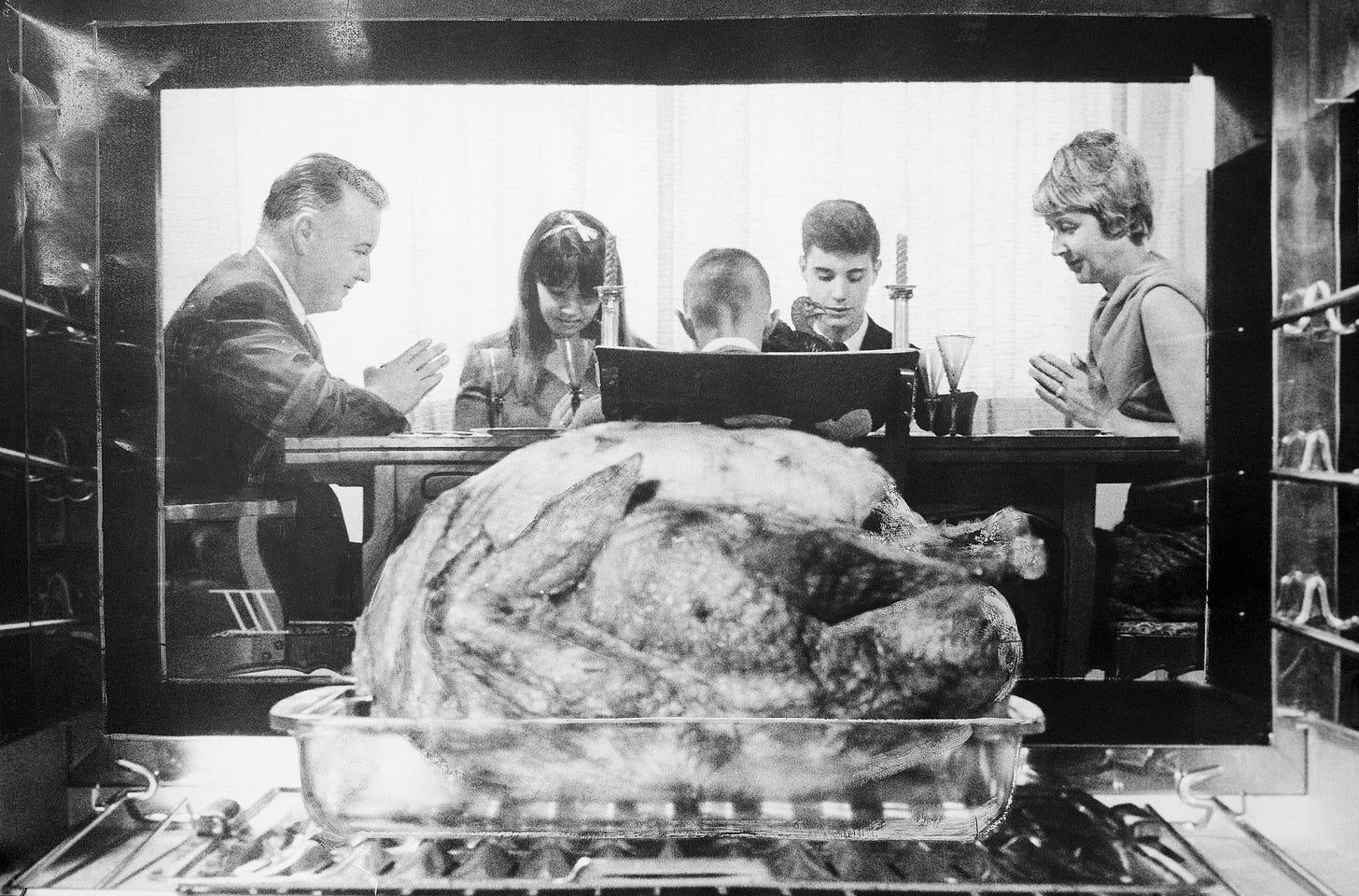

FOR THIS YEAR’S THANKSGIVING PRAYER, a theory: Gratitude is not just a virtue that serves an important social role, but it may just be the most underappreciated and underused tool for personal wellbeing.

We talk plenty about honesty, compassion, generosity, and openmindedness—all essential. But gratitude rarely gets equal billing, even though it’s the emotion that, more than any other, makes happiness possible.

If you want to avoid sinking into a pit of resentful disappointed despair, it’s vital to be grateful mindfully and actively and every day, not just on Thanksgiving.

Unfortunately, unlike sadness or anger or joy, the experience of gratitude is largely cerebral; it requires active consideration and reflection, and in our busy lives, may be difficult to find the time to attend to. Different faith traditions have different practices, including prayer, to encourage such thoughtful gratitude. Sometimes people invent practices of gratitude of their own. For my part, I have found it essential to have a routine I practice multiple times a day that helps me not drop all the wonder and appreciation between the cracks of everyday hubbub. For example, every time I notice Trump in the news (read: constantly), I have trained myself to think of my son who lives in Portugal and whom I don’t get to see nearly enough, thus using this pervasive irritant as a handy mnemonic for something positive.

Some time ago I heard about another example of such a practice, one that I am awed by. I have an acquaintance named Yisrael. He was originally named Chris and raised as a practicing Christian in a devout family in Philadelphia—but one day in adulthood he up and converted to Jewish orthodoxy, changed his name, and relocated to the nation which he’s now named after.

Yisrael is a good-natured fellow and also a standup comedian, which means he’s got a fairly thick skin, so on the occasion of our first meeting I broached the 800-pound kosher giraffe1 in the room: “What were you thinking? Why would you make such a choice? For that matter, do you even believe in God?”

(That was the gist, anyway; I may have been more politely delicate about it.)

Yisrael answered that growing up in his particular Christian denomination felt like “one long apology. Every prayer, every ritual, every moment of contact was me begging forgiveness for something I’d done wrong.” It left him feeling like “a perpetual failure in God’s eyes.” Most importantly it was missing what he needed most, which was a routine that prompted him toward constant recognition of and appreciation for the bounty that God had bestowed upon him. He didn’t want to apologize, he wanted to say Thank you!

Yisrael was quite surprised that it was in Judaism where he found such a routine—one that guided him into an endless cavalcade of expressions of gratitude.

It’s built into the mechanics of the faith. You wake up—you say thanks. You drink water—you say thanks. You eat bread, you say thanks. You drink wine—you say thanks, You prepare for sleep—you say thanks. Go to the bathroom? Thanks! Wash your hands? Merci! See a rainbow? Gracias! Hear good news? Arigatō! See a bird you’ve never seen (or anything else that’s a personal first?), תוֹדָה (toda)... and on and on and on—nonstop—all day—every day from morning to night—doesn’t matter how you’re feeling or what else is going on—you have to say thank you.

And when you make a habit of saying it, you’ll feel it. Even if 70 percent of those expressions of gratitude become so routine that you’re not even hearing yourself saying them, you’ll still notice the other 30 percent.

I’m not exaggerating when I say I felt chills. But what Yisrael discovered in Judaism contains a kind of universal secret. He wasn’t describing religion per se; he was describing a practice of constant, conscious thankfulness.

My own practice of gratitude looks different, but it’s what makes me love this holiday more than any other. Because the secret to contentment—real, lasting, deep contentment—runs straight through gratitude. You can’t feel blessed without it.

And the beauty is: You don’t need faith, or metaphysics, or a theology degree to experience it. This mechanism is available to everyone regardless of ideology. The focus of your grace can quite paradoxically be the feedback of satisfaction that you get from the grace itself. All you have to do is breathe.

Inhale deeply. Maybe the air carries a whiff of something tasty cooking, or the smell of damp leaves after an autumn thunderstorm, or that faint aroma of your grandmother’s kitchen magic when you were little. The air is full of these things. Or maybe you can just enjoy a deep breath and the sensation of your lungs filling up, the sensation of aliveness. And in that moment—what can you feel but blissful gratitude?

Happy Thanksgiving!

In fact-checking this piece, I found that elephants and gorillas, normally the subjects of the expression “in the room,” are not kosher but giraffes (technically) are. Make of that information what you will, but probably don’t use it to reconfigure your Thanksgiving dinner plans.