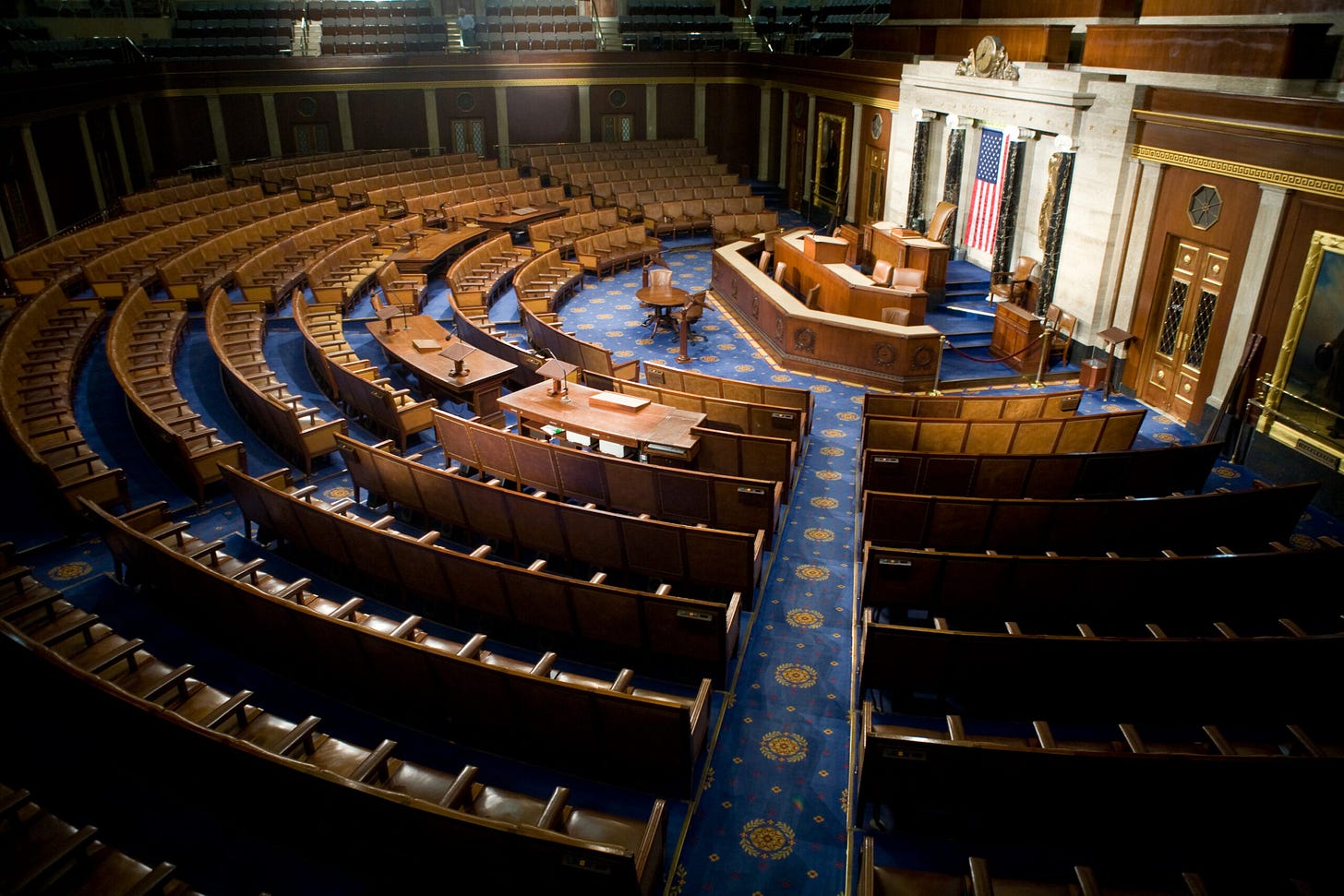

Americans Deserve a House of Representatives That Better Represents Them

A right-wing minority has outsized power in the House today. With proportional representation, that problem would be much less likely.

This month, the world was treated to the spectacle of the U.S. House of Representatives paralyzed for four days as Kevin McCarthy failed, ballot after ballot, to win the speaker’s gavel. He reportedly secured his victory by striking a Faustian bargain with the right wing of his conference, giving it a remarkable degree of power—to block and advance legislation, to sow chaos by pushing for a debt default, to run extremist candidates without opposition, and even to remove McCarthy from power on a snap vote. These concessions all but ensure the 118th Congress will be a microcosm of our political era. Expect bitter rifts, both within and between two dominant parties, one of which has been captured and held hostage by an authoritarian faction hostile to democracy itself; government divided on slim margins; and farcical political theater.

Yet away from Washington, something very different has happened. In Ohio, Alaska, and Pennsylvania, state legislative chambers all faced similar potential leadership impasses because of narrow margins, extremist factions, or both. But in all three states, groups within both parties united behind a consensus candidate or coalition.

This contrast between the far right setting the terms of governance in Washington and quiet cross-party coalitions coalescing in some state legislatures is not just surprising, it also helps reveal both the causes of dysfunction and the potential solutions in American politics.

Indeed, each of the three state examples reads like a fanciful alternative history to the House speakership charade. In Ohio, all 32 Democratic members of the House joined 22 moderate Republicans to box out the far-right candidate and elect a GOP state representative, Jason Stephens, as speaker. Stephens reportedly pledged to lead from the center and block far-right policies. In Alaska, the State Senate will be led by a bipartisan caucus of 17 Republicans and Democrats, with leadership positions divided across the parties. And in the Pennsylvania House, Democrats won more seats in November, but vacancies gave Republicans a slight advantage. After party leaders on both sides made competing claims that each controlled the chamber, a group of Republicans joined Democrats in officially electing as House speaker Mark Rozzi, a longtime Democratic state representative who promised to lead as an independent staffed by aides from both parties. Rozzi stressed that the speaker should be a “nonpartisan—and I want to repeat that, nonpartisan—officer of the House, entrusted with maintaining the integrity of the House.”

In other countries, these sorts of arrangements are common. Multiparty coalition building is the governing lubricant that keeps the lights on in most democracies. In Canada, Liberal Party Prime Minister Justin Trudeau holds office thanks to the support of Green Party and New Democratic Party members. Germany is led by a center-left coalition of Social Democrats, Greens, and Free Democratic (i.e., free-market) liberals. And it’s not just parliamentary democracies that are led by coalitions. France’s legislature is controlled by a coalition of six parties ranging from center-left to center-right. Most legislatures in Latin America, from Argentina and Brazil to Mexico, are controlled by coalitions of different parties. By our count, over sixty different countries are currently led by coalition governments.

So in a sense, the real question is not why cross-party coalitions are appearing in state legislatures, but rather, why they aren’t more common—and why a gridlocked House of Representatives refused to elect a consensus speaker backed by a majority drawn from both parties, instead caving to the demands of a small handful of extremist legislators.

The answer is that our system makes coalition building grueling, if not impossible. Over the last several decades, the trend toward nationalized politics and the increasing brightness of the media spotlight have made it more difficult for legislators to collaborate privately and negotiate in good faith, especially at the national level. Moreover, as legal scholar Richard Pildes notes, social media combined with a rise in small-dollar campaign donations allows “individual members of Congress to function, even thrive, as free agents.” It is difficult to imagine the Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Alaska outcomes happening under the glare of cable news or with social media provocateurs like Matt Gaetz and Lauren Boebert.

The United States is not alone in facing these trends, but the effects are aggravated by our winner-take-all electoral system, where each district elects a single, plurality-winner representative. This system strongly incentivizes politicians to coalesce into two vast, directly competing parties, leading to intra-party factions instead of several distinct parties. For a host of reasons, the two main parties have each become more ideologically distinct over the last few decades. This polarization is then exacerbated by primary elections: Any legislator who attempts to build a cross-party coalition—even in an exceptional situation like the current U.S. House—risks being shunned by his or her own party’s base in the next election. A wide range of research has found that primary elections disincentivize compromise in precisely this way.

This is true not just for the GOP, but also for Democrats, who could have offered Republicans an offramp during the speakership impasse earlier this month but had no incentive to do so. As unlikely as Kevin McCarthy was to reach across the aisle to cut a deal, he was just as unlikely to find a warm reception there, even among those inclined towards the possibility. Instead, the 212 House Democrats seemingly relished the theater (some literally bringing popcorn) and repeatedly voted against adjournment in hopes of keeping the embarrassing show going.

The good news is, these rules and incentives can be changed. Instead of electing our representatives through primaries followed by winner-take-all elections, we could instead transition to proportional representation, which avoids the harmful incentives of both.

With primaries and winner-take-all elections, voters choose from candidates who have been selected by a small portion of partisan voters. Each voter is then represented by a single person from a single party in each district. Under proportional representation, we would instead be represented by multiple officials, typically from different parties, who win seats in proportion to their votes. Political groups would secure seats not by winning individual districts outright, but by winning a sufficiently large bloc of support. That is, if a group—say, moderate pro-democracy conservatives—commands a fifth of the vote, it should expect to win roughly a fifth of the seats. Proportional representation therefore tends to create space for more parties, including centrist or moderate groups able to win elections without any allegiance to the extremes.

This shift to proportional representation could happen in a variety of ways, all of which involve expanding congressional districts to elect more than one member each, and allocating those seats under one of a number of different possible proportional formulas. One option can be found in Rep. Don Beyer’s Fair Representation Act, which uses a ranked-choice voting-based system (known to election scholars as “single transferable vote”), although most democracies opt for simpler systems where voters choose from lists of candidates put forward by different parties. Congress could also get out of the way and encourage states to experiment with different options.

In practice, our current system obscures, buries, and constrains the underlying multidimensional nature of our politics. Proportional and multi-party representation would surface that texture. As political scientist Lee Drutman writes, multi-partyism would transform Congress, since “no party would have a majority of seats. Instead, party leaders would need to work out a governing agreement.” And accordingly, “a far-right or far-left faction would have very little leverage, because a potential House speaker would have different possible coalitions to choose from.”

This ability to marginalize extremists is part of why so many eminent political scientists have called for the House of Representatives to move towards proportional representation. It also explains why most democracies around the world—many of which have studied the 250-year American experiment in representative government—use proportional systems instead of winner-take-all.

To be sure, most opponents of proportional representation also look to comparative cases, above all Israel, where multiple parties have come hand-in-hand with political instability. But, first, Israel is a clear global outlier—if the United States is the narrowest party system in the world, Israel is arguably the most expansive. Its formula for party representation is so over-inclusive that it generally produces a staggering ten to fifteen parties in the legislature. The answer is not to swing from the most restrictive party system to the least, but rather to pursue a goldilocks middle ground that encourages something like four to six parties, a balance found in most other advanced democracies.

Second, and more importantly, the supposed “stability” of the U.S. two-party system is in itself an illusion. Instead, our winner-take-all elections, which systematically advantage extremists, are imposing all of the costs of a fragmented political spectrum and none of the benefits of multiple parties and shifting coalitions. Indeed, the House Freedom Caucus is already acting like a third party, having secured a “European-style coalition government,” according to far-right activist Ed Corrigan. The rest of our political system’s failure to respond accordingly—by exploring other coalitional possibilities—is what gives the insurgents so much power.

No other peer democracy (again, most of which use proportional representation) has seen an insurgent autocratic faction capture both a dominant political party and the executive office. Even Israel, with recurrent elections and ever-shifting coalitions, has no problem keeping the government funded or not defaulting on its debt—both now permanent risks in the United States. In other words, we arguably are already among the least stable of democracies. By leaning into the shifting complexity of our politics, instead of ignoring it, proportional representation is likely to lead to more stability, not less. As political scientist Morris P. Fiorina argues, American voters (unlike Israelis) are surprisingly less polarized than most of us assume and “party sorting—not polarization—is the key to understanding our current political turbulence.”

Two other common concerns about proportional representation are likewise illusory. First, the fear that a reform of this magnitude is impossibly audacious. True, the effects would be sweeping, and most Americans today are unfamiliar with the concept. But multi-member districts were a common feature in the United States until 1967 (although they were still winner-take-all, without proportionality, and therefore were used to suppress rather than encourage representation). Legally speaking, implementing proportional representation is no more difficult for Congress than reforming the Electoral Count Act (which it did on a bipartisan basis several weeks ago), and a much easier political lift than abolishing the Electoral College, reforming the Senate, or ending Citizens United. Congress could embrace it tomorrow without amending the Constitution.

Second, there is the belief that proportional representation is politically impossible because it would break the two-party monopoly on power, so neither party would allow it to happen. Yet while it may theoretically go against the interests of the two parties, it is potentially very much in the interests of the politicians who make up those parties. Indeed, two prominent Democratic party leaders, Joe Neguse and Jamie Raskin, are cosponsors of the Fair Representation Act. And Kevin McCarthy’s life would likely be far easier negotiating with a centrist, free-market party than with the Freedom Caucus. The very fact that cross-party coalitions are emerging in state legislatures, even under winner-take-all rules, implies that current elected officials, all the way down, could thrive in a multi-party system. Proportional representation would free them to govern as they would prefer, to build more flexible alliances, and to run for office with party labels and platforms that more closely represent their constituencies. Politicians in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Alaska are already doing so, even when trapped in the rigidity of two parties.

The truth is that American politics already are a diverse network of interests that do not fit cleanly into two camps. In 2020, there were more Trump voters in California than any other state, and more Biden voters in Texas than in New York. As political scientist Steven Taylor says, “the institutions that shape our politics into only two parties [are] actually forcing a multiparty system into two boxes.” It is past time to free the diverse coalitions and complex dynamics of American politics from these cages, and to make the pragmatic coalition building we’ve seen in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Alaska the norm, not the exception.

Proportional representation for the House would not guarantee that the speaker’s gavel would always be held by a consensus-building leader. But it would make that outcome much more likely. And it would make less likely our present quagmire—where, as a result of the perverse incentives produced by a rigid two-party system, a small handful of the most politically extreme, authoritarian legislators will hold the entire House of Representatives hostage for the next two years.