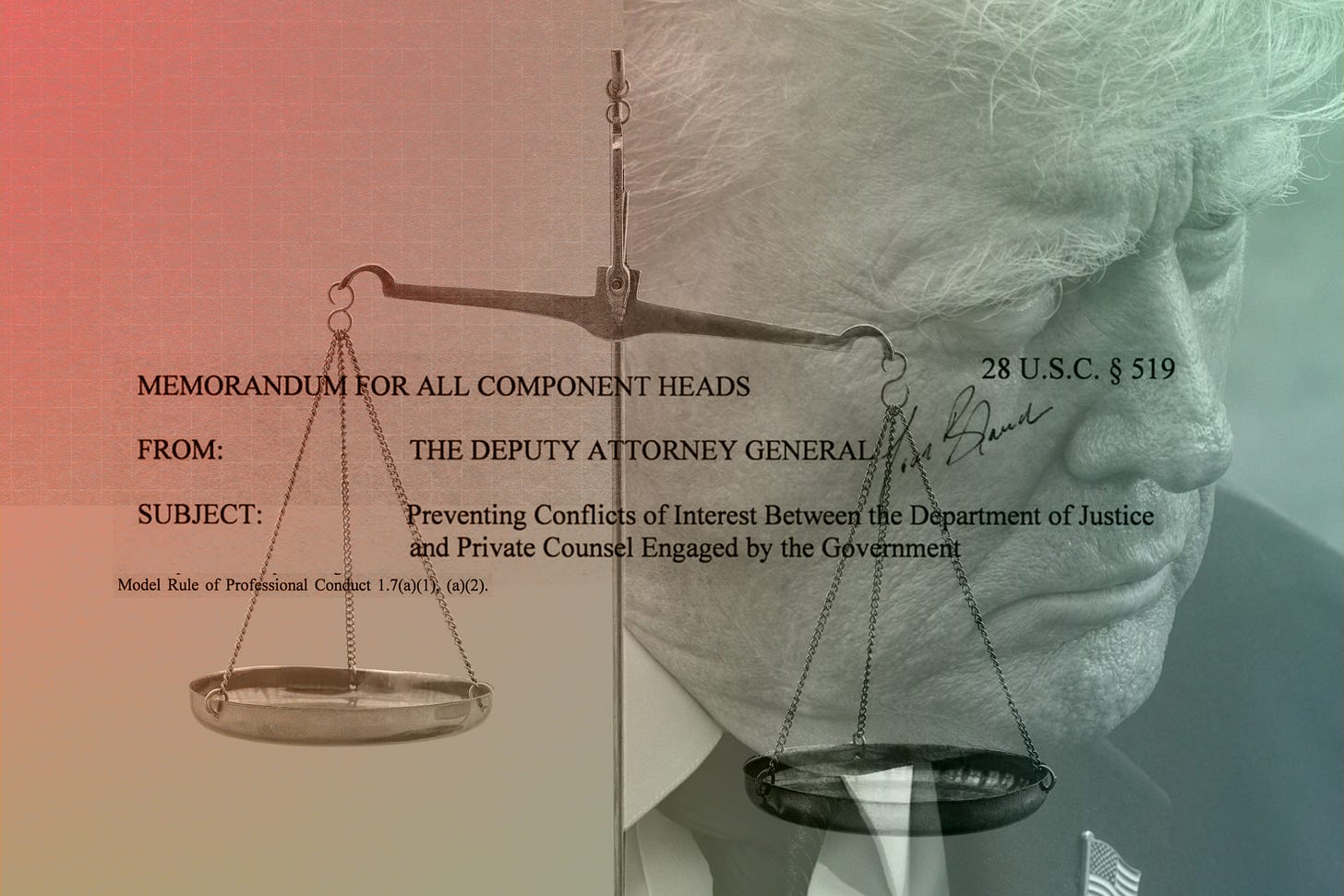

Big Law’s Big Choice

A D.C. Bar opinion shows why it would be ethical for the nine Big Law firms to rescind their settlement agreements with Trump. But to do so would invite his wrath.

CHICKENS, MEET ROOST.

When nine Big Law firms settled with Donald Trump (or, perhaps more accurately, cravenly “caved” to him), they probably thought that discretion was the better part of valor. Why fight with the big dog when the fight will only hurt, and when there is no apparent downside to surrender?

The downside has now become apparent. As reported in the New York Times, the District of Columbia Bar Legal Ethics Committee recently issued an opinion calling into grave question the ethical appropriateness of Big Law’s settlements with Trump.

Though the opinion does not mention Trump by name, the upshot of the opinion is that the big law firms that settled with him have to address significant ethical questions. Taken seriously, this opinion is a quiet earthquake that might shake the foundations of several law firms both because it says that what the law firms have done may have violated the Rules of Professional Conduct and because it also suggests that their violations cannot be cured without rescinding their agreements with Trump.

To see why, it’s worth backing up a bit to set the groundwork.

The D.C. Bar, like most other legal bars around the country, is a self-regulating entity that polices the conduct of lawyers who have their licenses from Washington, D.C. Part of that policing involves the creation and the enforcement of Rules of Professional Conduct (sometimes called rules of legal ethics, though that is a bit of a misnomer). These rules govern aspects of lawyers’ activities as they relate to clients—for example, they detail when and how lawyers create a lawyer-client relationship, when they may take fees, and when they must create escrow accounts.

To help educate lawyers about their obligations under these rules, the D.C. Bar has created an ethics committee that issues advisory opinions interpreting the rule’s provisions. Though the committee’s opinions are not binding law, they are authoritative guidance about questions of professional conduct for lawyers licensed in D.C. The opinions are often cited in formal disciplinary proceedings and, most notably, lawyers who follow the advice of the ethics committee get a measure of protection if they are ever sued for malpractice—they can, in effect, plead “I was following the advice I got from the committee.” Conversely, lawyers who ignore the opinions of the committee do so at their own peril.

One of the most important aspects of the Rules of Professional Conduct is a prohibition against conflicts of interest. For example, a conflict of interest might arise when one lawyer in a large law firm is representing a client (let’s call him Client A) and another potential client (Client B) wants to sue Client A. As a general matter, a lawyer cannot represent one client in a suit against another existing client—at least not without the consent of both of the clients.

But conflicts of interest do not arise exclusively between clients. A lawyer’s own financial or personal interests also may create a conflict between her clients and her. And so, the rules provide that: “a lawyer shall not represent a client with respect to a matter if . . . the lawyer’s professional judgment on behalf of the client will be or reasonably may be adversely affected by . . . the lawyer’s own financial, business, property, or personal interests.”

And this is where the Trump settlement agreements come in—the question is whether the law firms’ agreements with Trump create personal or financial interests for the law firms that may conflict with the interests of their clients—particularly when those clients are in turn suing the United States. Put bluntly, can a law firm really represent a client zealously against the Trump’s administration when, at the same time, it is seeking to stay on Trump’s good side through an settlement agreement?

The answer, as should have been obvious to the big law firms, is clearly “no.”

To be sure, the exact scope of the conflict is not publicly known. The settlement agreements between Trump and the firms are private. And so, we don’t know what promises the firms have made to Trump. We don’t even know whether the agreements are in writing or whether and how Trump can change the terms of the agreements (at his seeming whim). As one court said: “the publicized deals appear only to forestall, rather than eliminate, the threat of being targeted in an Executive Order.”

At a minimum, it seems clear that the Trump settlements will require the law firms to provide pro bono services support the president’s agenda. More insidiously, the settlement agreements also seem to require that, under threat of further sanction, the law firms will have to refrain from challenging Trump in other contexts. As one court put it, the agreements are a:

forward-looking censorship scheme [that] threatens not only the First Amendment but also the right to counsel’s promise of a conflict-free attorney devoted solely to the interests of his client. A firm fearing . . . an order like [the Orders] feels pressure to avoid arguments and clients the administration disdains in the hope of escaping government-imposed disabilities. Meanwhile, a firm that has acceded to the administration’s demands by cutting a deal feels the same pressure to retain the President’s ongoing approval. Either way, the [challenged] order pits firms’ loyalty to client interests against a competing interest in pleasing the President.1

In other words, what Trump is doing is an “attempt[] to deter law firms from offering their services to disfavored clients and from making disfavored arguments.” Any client whose legal position is adverse to Trump has to be wary of this possibility.

IN LIGHT OF THIS CONFLICT of interest, the D.C. Bar ethics committee made three important points. First, the committee said that the law firms need to disclose the substance of their agreements with Trump to their clients. Though it seems unlikely that any of the major Big Law clients don’t know about the agreements in the first instance, it is surely the case that they don’t know the details of those agreements—exactly what commitments their lawyers have made. Transparency is the first, and most important hallmark of dealing with a conflict. You can’t evaluate what you don’t know.

The identification and disclosure of a conflict of interest is not, however, all that is necessary. As the ethics committee put it:

A lawyer may proceed despite the existence of a such a conflict only if two conditions are satisfied: First, the lawyer must “reasonably believe” that she can “provide competent and diligent representation to each affected client.” . . . Second, the lawyer must “disclose the possible conflict to his client” and receive the client’s “informed consent” to the conflict “after full disclosure of the existence and nature of the possible conflict and the possible adverse consequences of such representation.

In other words, because the legal system values the idea of client control and their ability to pick the lawyers they want, most conflicts (not all, but most) can be waived. Client A can say “I know you are also representing Client B, but that doesn’t matter to me. I trust you, and I want you as my lawyer.”

In the context of a law firm’s agreements with Trump, that sort of waiver is not implausible. A big client (perhaps, a major company with a longstanding relationship with a large law firm) might reasonably say to itself: “We value our ties to the law firm. They know us and they know our business. We want to stay with them even though we know it is possible they may pull their punches. We trust them not to and we are willing to take that risk.”

And so, the D.C. Bar committee’s second point is that after disclosing the existence of a potential conflict of interest, the law firms in question must seek informed waivers of the potential conflict of interest from their clients. Thus, at a minimum, the law firm must get each client on record as acknowledging the potential for a conflict and affirmatively agreeing to go forward with the representation anyway.

One may be forgiven for suspecting that the Big Law firms don’t want to have to do that and that they may have been reluctant to do so in the past, for fear of losing revenue. But in the abstract, this kind of knowing and informed waiver from a big institutional client is quite plausible. Indeed, as most firms will tell you, the practice is relatively common, even if it is a bit of a pain.

The real sting of the ethics opinion, and the real source of a significant problem for the law firms that have settled with Trump, is that the indefinite nature of their commitments may make a waiver impossible to obtain. As the rule says, and the opinion makes clear, waivers must come from a client’s informed consent—that is, only after “full disclosure” of the nature of the possible conflict and the possible adverse consequences of a waiver.

But full disclosure cannot be made when the one party to the settlement is someone as mercurial as Trump. In the somewhat antiseptic language of the ethics committee:

As for the waiver option, if a law firm does not know what actions on their part might trigger adverse government action, the firm may be unable to provide the requisite “full disclosure of the existence and nature of the possible conflict and the possible adverse consequences of such representation.” That would mean, in turn, that clients could not provide the informed consent that is a prerequisite to a valid waiver. Similarly, if the precise nature and breadth of the commitments made by a law firm are unclear or are subject to change unilaterally by the government, the firm cannot be confident of its ability to remove the cause of the conflict because the conflict may reignite with little or no notice.

There are only three ways to eliminate a conflict—get an informed waiver from the client, drop the client, or remove the conflict. The D.C. Bar opinion makes clear that the waiver option may not be realistic. The firms may not in fact be capable of securing knowing waivers from their clients since the indefinite nature of their commitments to Trump render any disclosure almost by definition incomplete. And no firm wants to drop a big institutional paying client. But none of them are any happier following this analysis to its logical conclusion—that the only foolproof way to remove the conflict is by withdrawing from the agreement with Trump.

WHAT COMES NEXT is anyone’s guess. If the firms don’t seek waivers, they are violating the advice of the ethics committee and opening themselves up to malpractice claims in the inevitable circumstance that a case for one of the clients goes south. So, the firms will probably seek waivers from their clients. Their clients may even give them. But when, again, the case of any client goes south, that client will still have a claim that they were not fully informed about the nature of the firm’s conflict—and the D.C. disciplinary system might agree.

But if the firm does the “right thing” and drops the Trump settlements, then they will be subject to his wrath. That wrath might not be so threatening these days: Four non-settling, targeted law firms have succeeded in blocking Trump’s orders against them as unconstitutional. Still, Trump’s retributive nature is well known.

It is hard to feel any sympathy for the Big Law firms who settled. They are caught between Scylla and Charybdis—but it is a dilemma of their own making. But there’s an opportunity here, too: The firms should view the D.C. Bar Legal Ethics Committee’s opinion not only as a challenge to their past practice but as a chance to free themselves from subservience to Trump.

Some internal quotation marks have been omitted from this paragraph.