Every week I highlight three newsletters.

If you find value in this project, do two things for me: (1) Hit the Like button, and (2) Share this with someone.

Most of what we do in Bulwark+ is only for our members, but this email will always be free for everyone. Sign up to get it now. (Just select the “free” option at the bottom.)

1. YIMBY BABY

The more I look around the more I’m convinced that housing is the key to just about everything.

Want to increase economic efficiency by maximizing the labor market’s access to high concentrations of jobs?

Build more housing.

Want to encourage family formation and stable households?

Build more housing.

Want to eliminate homelessness and all of the attendant social problems that come with it—including crime, addiction, and abuse?

Build more housing.

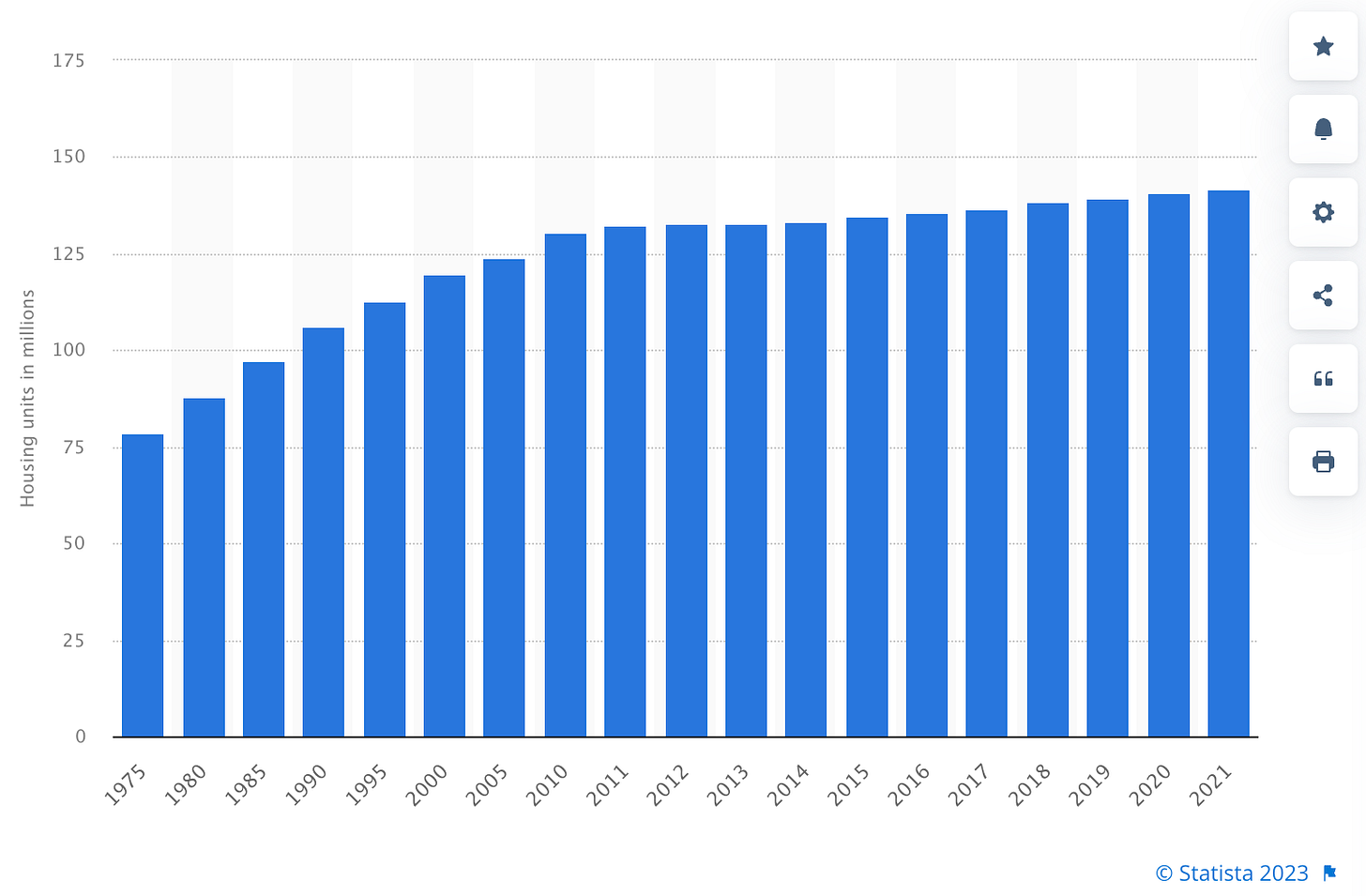

And recently we have not been building much housing. Look at the total inventory over the last 40 years:

Remember the great economic expansion of the 1980s? That just happened to coincide with an expansion in the number of housing units.

Now look at how flat the number of units has been since 2010. And guess what that’s done?

Prices went to the moon. Probably not a coincidence?

In a way, it makes sense that economic stagnation correlates to slow housing growth and large increases in housing correlates to robust economic growth. This has been going on for a century:

Housing starts, which peaked at 940,000 in 1925, had fallen by nine-tenths by 1933, to 93,000.25 The number of new houses started did not surpass the 1925 level until after World War II. Home ownership by non-farm families declined from 47 percent in 1930 to 41 percent by 1940.

Then came the end of WWII:

Marriage rates saw an immediate and dramatic rise at the end of World War II, with the discharge of several million soldiers from the military. More than 2.8 million new households were formed during the first two years after the war. High rates of new household formation continued into the 1950s, with the number of marriages in the United States peaking at 4.3 million in 1957. The birthrate also increased during this period, from 2.2 births per woman in the 1930s to 3.5 by the late 1950s. All of these returning veterans and newly married couples needed housing, which was in desperately short supply. Housing construction had been in a severely depressed state since the stock market crash of 1929.

Government officials estimated an immediate need for five million housing units after the war and more than 12 million over the following ten years. During the first several years after the war, millions of young adults and families had no choice but to double up with relatives, making the best of crowded conditions until more housing became available. Others lived in barns, garages, disused busses and streetcars, and anything else that could be pressed into service as shelter. The postwar housing crisis was alleviated over the course of several years by the building industry’s application of mass-production techniques to the construction of houses, and by the construction of housing tracts of unprecedented scale.

Again: That boom in the number of housing units coincides with the greatest sustained economic growth in American history. Good times.

This is all windup to Aaron Carr’s1 long post arguing that if you want to solve homelessness, you’re really talking about building more housing:

A failure or unwillingness to carefully look at the data has led countless people to believe that the primary drivers of homelessness are drugs, mental health, poverty, the weather, progressive policies, or virtually anything and everything that isn’t housing. And while some, but not all, of the aforementioned factors are indeed factors in homelessness, none of them, not a single one of them, are primary factors. Because if you want to understand homelessness, you have to follow the rent. And if you follow the rent, you will come to realize that homelessness is primarily a housing problem.

You can read Carr’s explanations as to why drug use and mental health aren’t the big drivers for homelessness. The key takeaway is this: Mississippi has a terrible healthcare system which does very little for people with mental illness. Mississippi also has one of the highest rates of drug use in the country.

And yet Mississippi has the lowest homelessness rate in America.

Why? Lots of cheap housing.

Carr gives a lot of data and then explains the not-at-all-counterintuitive truth:

[T]he places that have the highest housing costs, and the least housing supply, have the largest homeless populations.

Duh. Or take this, from the Economist:

The best evidence suggests that a 10% rise in housing costs in a pricey city prompts an 8% jump in homelessness.

Back to Carr:

If the primary problem of homelessness is housing, then the primary solution to homelessness is housing. And housing is indeed the solution:

Atlanta reduced homelessness by 40% through housing

Houston reduced homelessness by 63% through housing

Finland reduced homelessness by 75% through housing

Tokyo reduced homelessness by 80% through housing

But as important as housing supply is to reducing homelessness, places like Houston also demonstrate the importance of going beyond it.

Houston has always had a significantly lower rate of homelessness than other large cities, like New York City and Los Angeles, because unlike those cities, Houston builds a lot of housing.

Look: You can’t force developers to build housing. But you can make it easier for them by killing anti-housing NIMBY regulations. And you can undo the perverse incentives that lead some developers to treat real estate like NFTs.

And these changes will ultimately be good not just for the homeless, but for everybody.

2. Gone with the Wind

The Oscars are Sunday and the Ankler is so awesome that they’re now publishing the kind of long-form essays that I’d usually hope to find in the New Yorker.

David Vincent Kimel is a historian who’s obsessed with Gone with the Wind. How obsessed? He paid $15,000 for one of the movie’s last surviving shooting scripts. (Producer David O. Selznick had ordered all shooting scripts to be destroyed.)

Working through this script and comparing it with other historical documents, Kimel has pieced together the story of how Selznick grappled with the movie’s depiction of slavery. And this isn’t some woke, modern conversation. Gone with the Wind was filmed in the late 1930s and even at the time the story’s depiction of slavery was a contentious subject among the writers, producers, and studio.

But before we get into that, Kimel reminds us that the past isn’t even past:

At the Atlanta premiere of Gone With the Wind on December 15, 1939, the 10-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. was dressed as a slave. It was the second night of an official three-day holiday proclaimed by the mayor of Atlanta and the governor of Georgia. King’s choir was serenading a white audience, directed to croon spirituals to evoke an ambiance of moonlight and magnolias for the benefit of the movie’s famous producer, David O. Selznick.

Holy crap.

But let’s move on to the real story:

As Selznick watched King and the Ebenezer Baptist Church choir sing, and white Atlanta swirl around in giddy celebration of his epic movie, the producer harbored a shocking secret never revealed until today: a civil war that had roiled the production internally over the issue of slavery, with one group of screenwriters insisting on depicting the brutality of that institution, and another faction, which included F. Scott Fitzgerald, trying to wash it away. Selznick’s struggles over the exclusion of the KKK and the n-word from the script and his negotiations with the NAACP and his Black cast are the stuff of legend. But the producer’s decision to entertain scenes showcasing the horrors of slavery before deciding to cut them has never been told . . .

I discovered this untold history of Gone With the Wind after I stumbled on an antique shooting script for sale at an online bookstore three years ago. I knew immediately the screenplay was an amazing find since, according to the auction at which it originally sold, Selznick had ordered all shooting scripts destroyed. This was one of the last surviving “Rainbow Scripts”, named for the multi-color pages inserted to reflect the famously obsessive producer’s revisions, which continued to pour in even until the final days of the production. I saw that the 301-page script was authenticated for the previous owner by Bonhams, one of the most prestigious auction houses in the world, so I bought it . . .

When I started reading the Rainbow Script, I found it even more incredible than I could have imagined. It was full of lost scenes cut from the movie between February 27, 1939, when the first inserts were added, and some time after June 25, 1939, when the last of them were dated. Some of these scenes were known to me by legend and research, but most of them were never described anywhere else before.

On-set photographs depict some of these lost scenes, confirming that several of them were actually shot. If this material were ever exhibited, it would have been in Riverside, Calif., on Sept. 9, 1939, when Selznick tested the unfinished film in front of a rapturous audience after literally locking them into the Fox Theater and unexpectedly commandeering a double showing of Hawaiian Nights and Beau Geste.

If you love movies and/or care about their cultural impact, then you simply have to read this piece. It’s amazing.

And subscribe to the Ankler while you’re at it. Journalism like this ought to be supported.

3. Woke Studies

Steward Beckham writes about how “woke” became the new “liberal.”

The term “woke” has become a weapon for conservatives to attack Democrats and left-leaning Americans as cultural authoritarians. In actuality, “woke” became popular again in the late-2000s with an Erykah Badu song . . .

But “woke” was becoming a mainstay in popular culture and politics by the mid-2010s, despite the term being much older. For example, there was a popular song by the artist Childish Gambino also known as Donald Glover, the talented creator of the series Atlanta . . .

Woke became a popular term used by young people to describe an act of gaining enhanced knowledge about deep-seated national failures regarding racial identity and demographic inclusion. It is also characterized as a general openness to acknowledging and stating the ways in which white supremacy has mired America’s ability to live up to its democratic potential. The awakening coincides with the fallout of America’s unwarranted invasion of Iraq, a radicalized Republican Party squeezing the middle class while openly harming minority Americans through unequal economic distribution and voter suppression, as well as revelations regarding how women have been sexually abused and attacked in the workplace by powerful actors. . . .

In recent years, conservatives have jumped on “woke” to paint their political opposition as obsessed with condescending attempts to socially engineer people’s behaviors and customs. They are intrinsically speaking to older Americans (and less educated ones), who shed anti-Black attitudes, antisemitism, homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia, and other forms of hate and willed separation.

In sum, Beckham argues that “bad faith conservatives did to ‘Woke’ what Baby Boomers did to Facebook.” And that there’s historical precedent for this sort of thing.

Read the whole thing and subscribe.

And if you find this newsletter valuable, please hit the like button and share it with a friend. And if you want to get the Newsletter of Newsletters every week, sign up below. It’s free.

But if you’d like to get everything from Bulwark+ and be part of the conversation, too, you can do the paid version.

I originally said the housing post was written by “Aaron Blake.” That’s wrong—it’s “Aaron Carr.” The error has been fixed throughout. Deepest apologies—no excuse for that sort of mistake.

If you want to explode your head, come walk around my n Arlington neighborhood and see the BLM signs side by side with signs opposing a county proposal for *very limited* rezoning to allow some multi fam housing in our exclusively SFH neighborhood. Smh. Separately, I think converting all these empty office buildings into apartments is a good idea, although I’ve been told it’s not so easy to do structurally.

I feel like today's Triad was custom picked for me. I'm getting a seat on my town's planning commission so I'm trying to read up on everything housing/urban planning related.

But I'm also a huge (its like a shameful secret) Gone With the Wind fan. I know stupid amounts of useless trivia about the film, had the movie poster hanging in my dorm room closet, and have revised and re-revised my opinion of the film as I've grown up, but I still think it's really important to the American legacy of film, and I love a good nuanced take on the film. You had me at rainbow script.

I have less of an issue with the fact that GWTW exists as a depiction of the civil war, and more of an issue with the fact that Hattie McDaniels and Butterfly McQueen couldn't get better roles after the movie ended. Or that it took decades and decades to make a movie like 12 Years a Slave or Harriet or Emancipation.

Ultimately I think the script accomplished what it set out to do: tell the story of the civil war from the standpoint of white slave owners. The problem is that viewers weren't interested in the other perspectives. But its white slave owners are awful. We root for Scarlett, but she's a selfish and morally bankrupt person, Ashley is a wimp who argues in favor of consanguinity, Rhett is a rapist, Melanie is naïve to the point of idiocy (A dynamic delightfully skewered in Carol Burnett's retelling of GWTW. A must watch for any fan. Or anyone who hates the movie. It's funny either way). I've always gotten the impression that the confederate apologists who defend the movie never actually sat through all 4 hours of it. I mean by the time it ends Scarlett's first 2 husbands and child are dead, her current husband is leaving her, and her lover is mourning his dead cousin/wife. I think it's pretty hard to say Gone with the Wind is a ringing endorsement of any of it's characters beliefs or behaviors...