Committing to Democracy

Lessons from the life of Lincoln—a review of Allen C. Guelzo’s ‘Our Ancient Faith.’

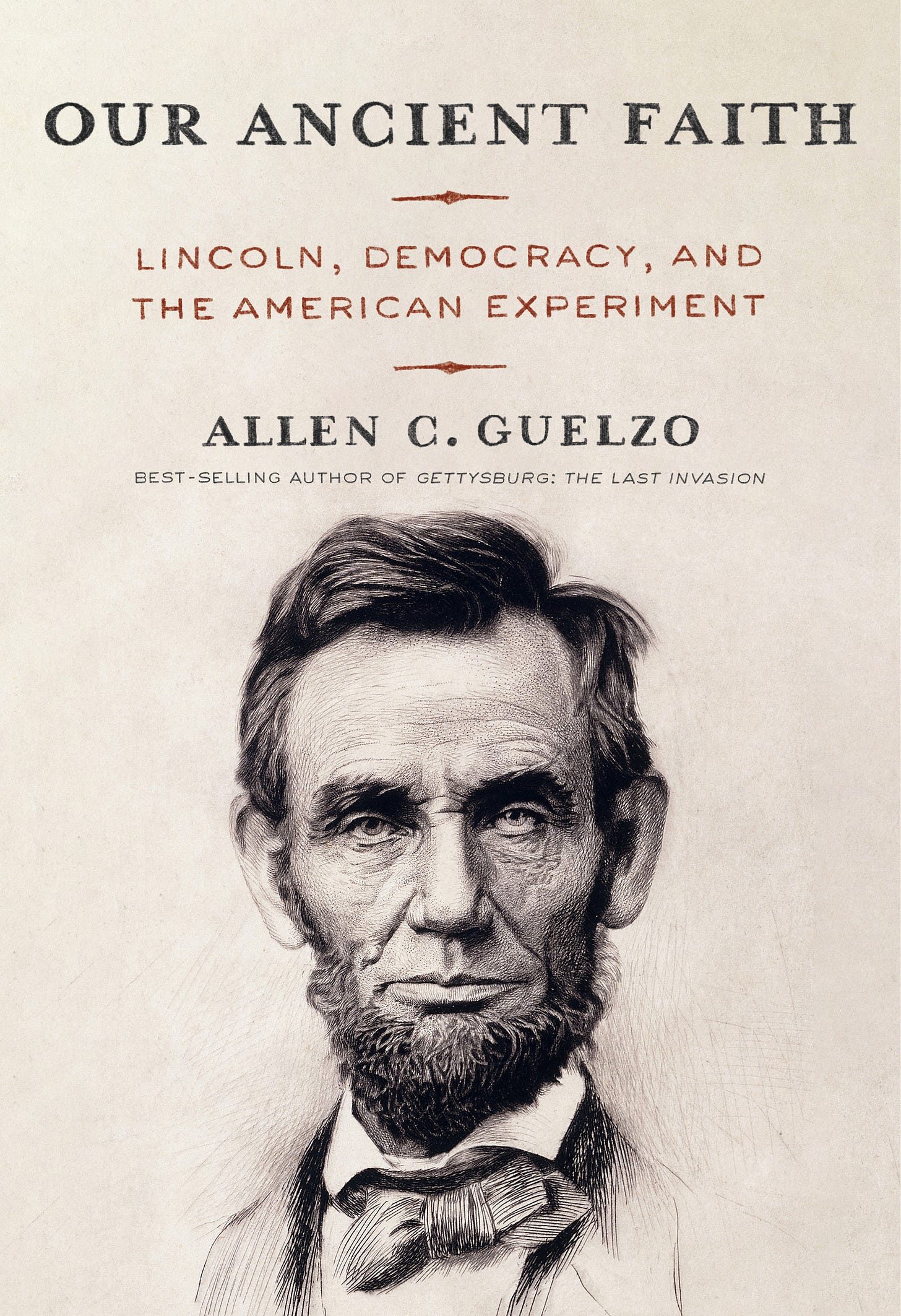

Our Ancient Faith

Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment

by Allen C. Guelzo

Knopf, 246 pp., $30

AT A MOMENT WHEN A GROWING NUMBER of Americans are questioning whether democracy still works and is worth fighting for—and when a Republican presidential candidate reignited the debate over the causes of the Civil War and Republican governors are openly flirting with nullification and secession over border policy—the ideas and career of Abraham Lincoln remain as relevant as ever. Civil War historian and Lincoln biographer Allen Guelzo, in his eighteenth book, Our Ancient Faith, offers a short, punchy deliberation on Lincoln’s relationship with democracy.

In a series of concise topical essays, Guelzo explores the relationship between democracy and the economy, property, race, freedom, elections, war, and inequality. He also considers the unique characteristics of American democracy and its shortcomings, and draws on Lincoln and his times to make his case.

Guelzo offers three basic tenets of American democracy: the rule of law, consent through representation, and majority rule with a toleration of minorities. All democracies must balance majority rule and the protection of minority interests, a balancing act especially complicated in a democracy as large and diverse as the United States. Central to maintaining that balance are citizenship (the participants in the political system are designated as citizens with rights), elections (both majorities and minorities can vote to express their preferences), and public forums (for discussion and association). According to Lincoln (and Guelzo), political participation is indispensable—not a privilege but a duty.

The flip side of public participation, however, is an embedded weakness for demagogues. Lincoln particularly feared the reign of mobocracy. He was suspicious of any great political passions, whether arising from nativism or violent white supremacy, for their tendency to lead to mob rule. Lincoln treasured reason as the natural check on passion, and the rule of law as the bulwark when reason failed.

GUELZO ASTUTELY NOTES that “Lincoln could not dodge the terrible fact that the Civil War was a moment of failure, and so serious as to cast a shadow of doubt over the viability of democracy itself.” The fact that the war came felt like, and was described at the time as, a tremendous failure. The darkness is critical to the story and makes both the victory and Lincoln’s talents more remarkable.

Guelzo’s argument about the economy is less compelling. Lincoln viewed commerce as the full partner of democracy, interpreting “all men were created equal” to mean that all men should have equal opportunity to better themselves, not that their experiences or end results should be the same. Accordingly, equal opportunity to earn wages, acquire property, and pursue education were central to citizenship under a democracy. Slavery was the ultimate perversion of this principle because it prevented enslaved African Americans from earning a wage for their labors—which is why Lincoln hated it.

Guelzo naturally gives prominent placement to Lincoln’s thoughts on commerce and the economy. However, he makes a few errors along the way. Some are small, as when, in emphasizing how much changed during Lincoln’s lifetime, Guelzo suggests that the world was lit by candles until 1855 when the kerosene lamp was invented, even though oil lamps were already increasingly common at the time of Lincoln’s birth. Some of the errors are larger, as when Guelzo argues that Lincoln and the Civil War radically transformed the United States from a subsistence economy (which, Guelzo writes, had prevailed “anywhere beyond the reach of American towns”) to a market economy. In a subsistence economy, farmers largely barter and trade their goods locally for other products and goods. Farmers in market economies ship their goods to market for profit or credit. The extensive literature on the market economy of the eighteenth century rebuts this assertion, as does the Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s. Farmers in Western Pennsylvania regularly turned their excess corn and grain into alcohol, which they shipped to Eastern markets for sale. They resented the 1792 excise tax on whiskey stills because they (correctly) argued that the tax unduly burdened western regions. The Whiskey Rebellion—which Guelzo mentions several times—was a product of the market economy.

Finally, Guelzo offers a muddled assessment of the fundamental legislation passed during Lincoln’s administration. He points to four key policies that transformed the economy: tariffs, monetary policy to fund the Civil War, the Homestead Act, and the proliferation of railroads. “Even had there been no civil war,” Guelzo argues, “it is safe to say that Lincoln’s administration would still be regarded as a hinge presidency in American history, if only for the way his economic policies inaugurated a new political generation that glorified free labor, protective tariffs, and federal encouragement for infrastructure.”1

But is it really true that those policies would have been enacted “even had there been no civil war”? Guelzo himself acknowledges that the Homestead Act, which opened government-owned lands in the West to settlement, passed only because Southern congressmen had abandoned their positions and left Washington, D.C. Versions of the Homestead Act had been debated for years but had been stymied in debates over the expansion of slavery in these territories.

Indeed, none of the four policies (tariffs, monetary policy, the Homestead Act, or the railroads) would have passed with Southerners seated in Congress. For example, both Northerners and Southerners advocated federal investment in the railroad, but they disagreed about where to place the lines. They recognized that rail lines would benefit the communities near them and they were all eager to bring that economic advance to their home states.

None of these mistakes derails Guelzo’s larger argument, but they are unforced errors. The explosion of economic growth and the transformation of the United States during Lincoln’s lifetime are extraordinary enough without exaggeration.

OUR ANCIENT FAITH IS NOT A BIOGRAPHY and so does not offer comprehensive coverage of Lincoln’s life from birth to death; Guelzo assumes his readers share at least a basic knowledge of Lincoln’s story. He does offer thoughtful considerations about what it means to have and keep a democracy, but I’d encourage readers to assess for themselves how Lincoln applies to today.

I agree with Guelzo’s underlying premise: Lincoln offers wisdom for the ages. But he feels especially poignant right now. Lincoln understood that a commitment to democracy was more than just committing to elections. It is a much deeper pledge to a set of principles. Without those principles—“mores” in nineteenth-century parlance—democracy cannot last. We experienced this weakness on January 6th. The peaceful transfer of power doesn’t mean much if citizens and officials don’t cherish and uphold it.

Lincoln saw the war as an opportunity to renew those principles, even if at a terrible cost. In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln hoped the sacrifice of those who “gave the last full measure of devotion” would usher in “a new birth of freedom.” Now, the task fell to “us the living . . . to be dedicated here to the unfinished work” of preserving a “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Guelzo rightly notes that democracies are often dangerously slow to appreciate threats to their safety, whether foreign or domestic. When finally alert, however, democracies have the capacity to harness enormous energies to fight their enemies. Maybe in this moment, we’ve been perilously slow to grasp the weakness of our democracy. But now that we are here, we can embrace the opportunity to usher in another “new birth of freedom” and increase our devotion to American democracy.

Perhaps Lincoln’s understanding of what mattered most was his greatest contribution. We should be willing to compromise on most things—but not on fundamental principles. By the late 1850s, Lincoln understood that, as Guelzo puts it, “slavery was not a conflict that was going to be talked away.” Lincoln still favored measures to avoid war, but he had concluded that “this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” Lincoln’s driving purpose was to preserve the Union. He would compromise on anything in service to that goal, but not the goal itself.

Which is why Guelzo’s conclusion is puzzling. He points to two present-day threats to democracy: the federal bureaucracy and the federal judiciary. There are legitimate and serious debates to be had about the expansion of the executive branch paired with the abdication of congressional oversight. Similarly, I see the appeal of reining in the Supreme Court’s activism, whether it is in the Warren or Roberts court. But these concerns seem better suited to the 1990s than today. Not that the arguments are outdated, but rather they feel like the product of a lost world in which those were the most pressing challenges.

The conclusion parallels a bit of bothsidesism in the book’s beginning. Guelzo condemns both the “woke” progressives who argue that “the promises of American democracy are falsehoods, maintained by the powerful in order to oppress the marginalized” and “the ‘religious integralists’ and ‘national conservatives,’ who have concluded that democracy in America has granted too much autonomy to the individual over the community.” Both groups “yearn to rule” and work to capture the bureaucratic state for their own purposes.2

But this comparison misses the forest for the trees. No matter what talking points you might hear on Fox News, the “woke” left doesn’t control the Democratic party or the sitting Democratic president, who has repeatedly pushed back against the fringes of his party. By contrast, it is the fringe on the right that currently holds the levers of power in the House of Representatives and dominates the primary process.

The biggest threat to American democracy today is posed by an intense and vocal minority who have seized control over the Republican party. They seek to destroy our democracy; they speak openly of dictatorship and overthrowing any election in which they lose. Once that threat is defeated, I’d be delighted to return to debates on the limits of bureaucratic authority or judicial overreach. Per Lincoln’s values, the existence of our democracy is not a subject of compromise. It either exists or doesn’t. Once we solve that question, we can compromise on the other stuff.

To the list of Lincoln-era policies with a transformative economic effect Guelzo could also have added the legislation creating the land-grant university system, which has had a profound and lasting effect on American society and the economy.

Emphases in original.