How to Think About Ukraine’s War on Corruption

What Americans see as symptoms of an endemic problem, Ukrainians themselves see as antibodies and signs of hope.

BIG NEWS FROM UKRAINE LAST WEEKEND didn’t register for most Americans relaxing for Labor Day or busy getting the kids back to school—and for those who did notice, the response seems to have been little more than a tired, there-they-go-again shrug. After all, what’s new about Ukrainian corruption scandals?

In fact, the story is much more complicated and important—and worthy of American attention. Ukraine’s war on corruption is closely linked to the war it’s waging on the battlefield. Losing the fight against graft and influence peddling would doom the new nation Ukrainians want to build as much as a forever war with Russia. And in this case, too, as with the shooting war, Americans and Europeans can help.

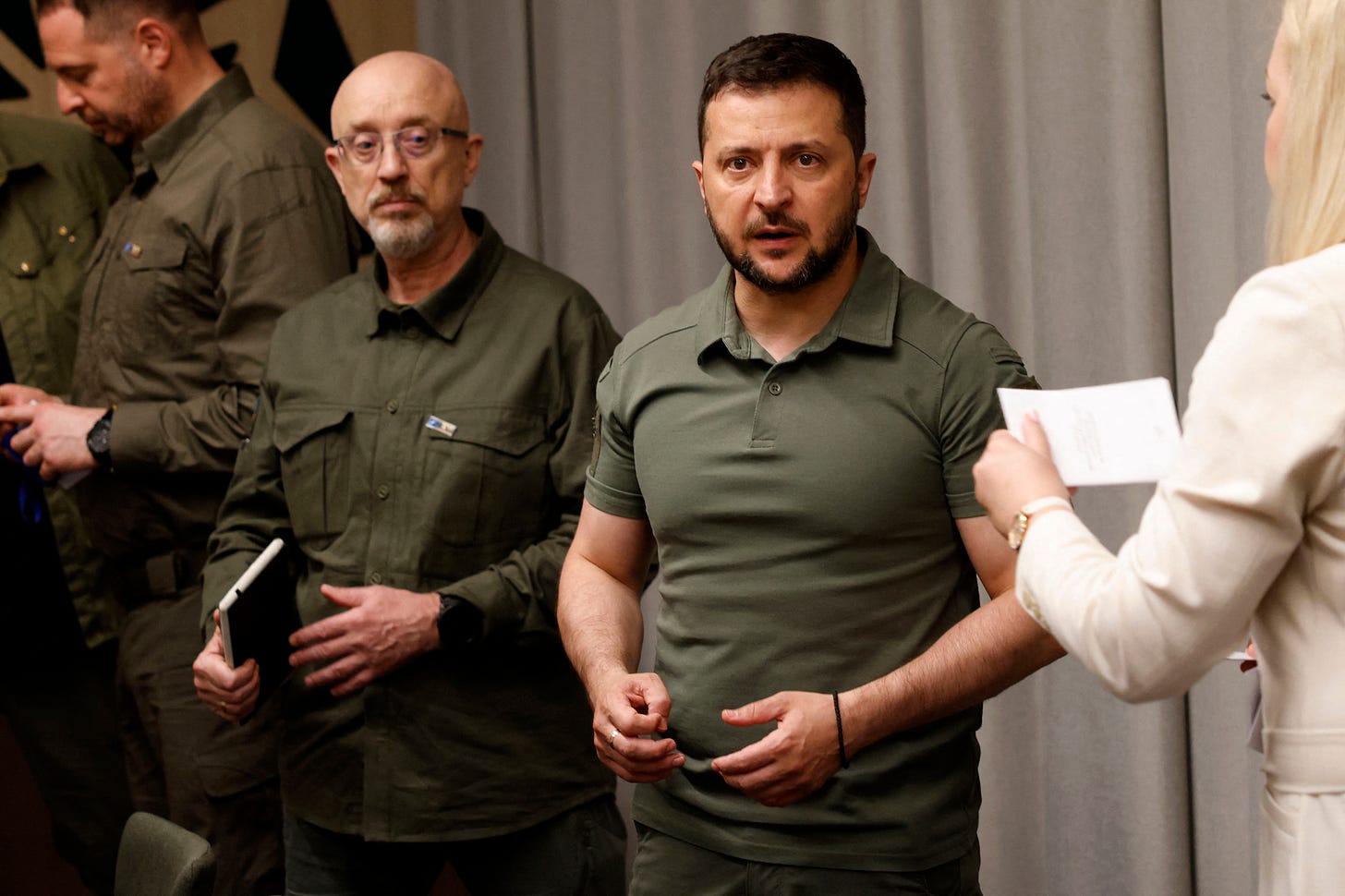

The headlines from Ukraine over the weekend: President Volodymyr Zelensky fired the defense minister, Oleksii Reznikov, who has stood loyally by him through 18 months of war. Zelensky also arrested his erstwhile patron, oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, a major backer of his 2019 presidential campaign and owner of the television station that hosted the popular TV show that launched his political career.

The two cases are very different. Reznikov has been accused of no wrongdoing, but he mishandled the media and alienated voters when he stonewalled recent investigations into military procurement scandals involving overpriced eggs and overcoats. Kolomoisky, one of Ukraine’s richest men and a target of U.S. State Department sanctions, is under investigation for $13.5 million worth of money laundering and fraud. What the two men have in common: Both were once in Zelensky’s inner circle—and going after them sends an unmistakable signal to Ukrainian voters.

Many Americans who heard the news viewed it yet another symptom of what they see as Ukraine’s endemic corruption—this instance all the more unsavory because it appears to be undermining the war effort. By contrast, for many Ukrainians, the crackdown was a reason for hope, evidence that the president may be getting serious about going after unscrupulous officials and oligarchs. Where Americans see germs, Ukrainians see antibodies.

BUT THE ISSUE GOES DEEPER than a simple perception gap. Outsiders often assume that Ukrainian corruption is intrinsic or inherent, so deep-seated that it’s all but immutable. Most Ukrainians know better—they know that today’s bad habits were learned in the past and can be unlearned. The mindset that produces graft and extortion isn’t innate or hardwired. It was inherited from the Soviet era, when all political power was derived from patronage and when chronic shortages of goods and services made it impossible to survive without barter and bribery.

No one in Ukraine or America thinks that change will be easy. But Ukrainians have watched for nearly a decade as idealistic young reformers bent on eliminating corruption have fought an unrelenting battle against the old guard—politicians, oligarchs, and other vested interests determined to maintain the post-Soviet status quo.

The idealists emerged from the Maidan Revolution of 2014, when a million Ukrainians took the streets and deposed pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. In the wake of the protests, many activists gravitated to small grassroots anticorruption groups, formal and informal, some focused locally, others working at the national level. Some started with protests and press releases. Others developed legal cases and tried to take the old guard to court. Foreign donors provided funding to develop digital tools, including a groundbreaking online platform, ProZorro, to track public procurement nationwide. And over time, the grassroots groups grew into a formidable democratic opposition that worked with reform-minded lawmakers to create a set of national institutions—specialized detectives, prosecutors and a dedicated court—devoted to fighting corruption in all its forms.

The old guard hasn’t given up easily. Lawmakers beholden to oligarchs delayed reform legislation or rendered it toothless with hostile amendments. Unscrupulous prosecutors removed powerful politicians’ names from indictments. Corrupt judges blocked criminal cases and dismissed charges against fellow jurists. President after president campaigned on promises to root out wrongdoing but then kowtowed to the oligarchs or made a show of combating corruption while actually protecting friends and allies. In other instances, when its interests were most threatened, the old guard fell back on smear campaigns and physical violence. Between 2014 and 2018, according to one human rights group, there were about 100 attacks on anticorruption activists, and 10 activists were murdered.

As recently as February 2022, when Russia launched the full-scale invasion, it was hard to tell which side was winning this struggle—civil society reformers or the old guard. What has made a difference in the past 18 months: International pressure has tipped the scales in favor of the anticorruption activists and triggered a handful of small but important changes that have freed the national anticorruption institutions to get on with their job.

The detectives and prosecutors of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office answer to new bosses installed in the past year under pressure from the European Union. Also at the EU’s insistence, the bodies that select and discipline judges have been reconstituted with new personnel, and they are poised to select some 2,500 new judges for high and low courts nationwide—a sweeping, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for reform.

The High Anti-Corruption Court has issued nearly 150 verdicts since it launched four years ago, and it is building a reputation for subtle, responsible jurisprudence. Most important, according to reformers, even the most powerful corrupt officials no longer operate with impunity. Today, unlike in the past, they know they can be caught and tried and may end up in prison.

THE BOTTOM LINE: NOTHING COULD BE LESS HELPFUL than to shrug this off as there they go again. The Ukrainian war on corruption is in high gear, as fierce a battle as the fighting on the southern front. The reformers have the momentum, and their war looks increasingly winnable. But they too need help from the West—mainly, pressure they can use to hold the old guard’s feet to the fire.

Membership in transatlantic alliances like NATO can and should be conditioned on reform. Investment for reconstruction should come with strings attached, including detailed accounting and long-term oversight. Just how the battle is waged can make a crucial difference, and the reformers don’t always agree with Zelensky’s team about what’s needed or which government body should take the lead. Zelensky often relies on agencies that answer directly to him, while most reform advocates prefer the specialized anticorruption institutions, which are more likely to be independent and impartial.

What’s needed from the West: close, sustained attention to the war on corruption, and tough love. Ukraine’s American friends shouldn’t turn a blind eye to the corruption problem—shouldn’t be afraid to talk about lingering issues or insist they be addressed. But nor should opponents of U.S. aid to Ukraine be allowed to hide behind old stereotypes of a hopelessly, endemically, immutably rotten culture. Neither approach fits the facts, and neither serves America’s interest in an independent, democratic Ukraine fully aligned with the West.