How Close Were Epstein’s Ties to Russia, Really?

There’s no solid evidence he was a Russian asset, and it’s unlikely he had any ties to Putin. But evidence of sleaze and abuse abounds.

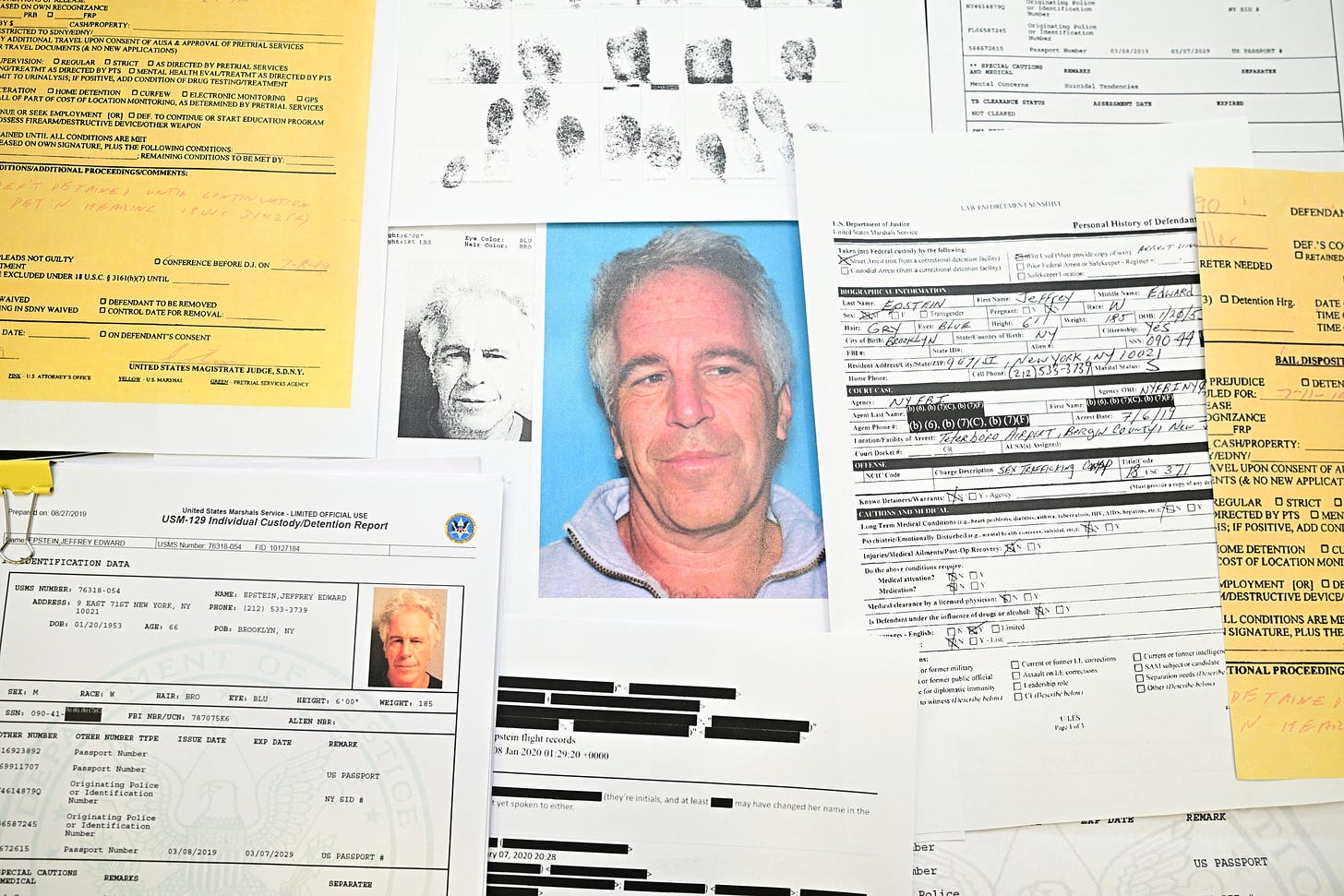

AN UNEXPECTEDLY PROMINENT new subplot has emerged following the recent release of millions of additional documents from the Epstein files: an alleged “Russian trail.” The voluminous evidence of Jeffrey Epstein’s contacts with various Russians, some of whom had ties to Russia’s spy agencies, has led some observers to conclude that the multimillionaire financier, sex trafficker, and rapist was also an intelligence asset belonging to the Kremlin.

Citing “intelligence sources,” the Daily Mail, the British tabloid, recently reported that Epstein was “running ‘the world’s largest honeytrap operation’ on behalf of the KGB when he procured women for his network of associates.” Then, last Tuesday, Polish prime minister Donald Tusk announced an inquiry to assess whether Epstein had links to Russian espionage—and whether Russia might have Epstein-related compromising materials on various political leaders. It should come as no surprise that Tusk’s remarks gave a boost to theories that Vladimir Putin has kompromat on Donald Trump.

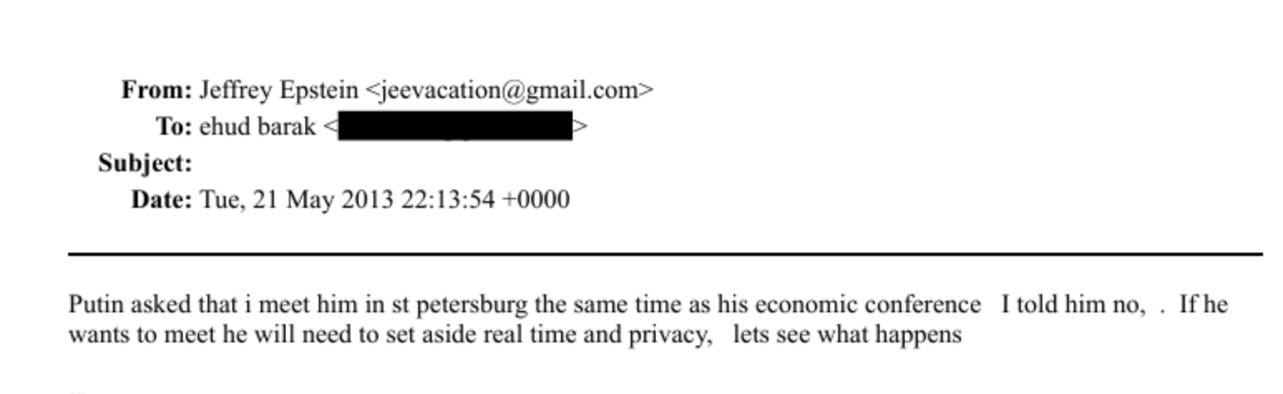

But as with much else in the Epstein story, the facts are often enmeshed with thinly sourced speculation. For instance, while the Daily Mail has some interesting information on Epstein’s Russian contacts, its headline contains the unsupported assertion that Epstein “had multiple talks with Putin after conviction.” But the article itself hedges this claim, saying only that Epstein “seems to have secured audiences with Putin” after his 2008 guilty plea (to two counts of solicitation, including solicitation of prostitution with a minor). A look at the relevant files shows that Epstein talked repeatedly about such meetings; but, as the independent Latvia-based Russian news site Meduza concludes, “There’s no evidence in the released files that a meeting between Putin and Epstein ever took place.” Notably, in May 2013, Epstein claimed to former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak that he had turned down Putin’s invitation to meet:

The conference in question, the annual St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (held in June), was partly coordinated by Epstein’s pal Sergei Belyakov, who was then serving as Russia’s deputy minister for economic development. (More about him later.) This lends some credence to the possibility that there was, in fact, some talk of Putin meeting with Epstein on the forum’s sidelines. On the other hand, Putin asked me to meet, and I told him no is just the sort of thing a clout-obsessed narcissist would tell a powerful friend, and so far, no other evidence seems to have turned up in the files to support the idea that Putin made such a request.

A September 11, 2011 email to Epstein from a sender whose identity has been redacted says, “Spoke with Igor. He said last time you were in Palm Beach, you told him you had an appointment with Putin on sept.16, and that he could go ahead and book his ticket to Russia to arrive a few days before you.” “Igor” is Epstein’s then-bodyguard and personal trainer Igor Zinoviev, a Russian mixed martial arts fighter who emigrated to the United States in the 2000s (and gave a fascinating, very cagey interview to New York magazine after Epstein’s death in 2019). But once again, there is no evidence that such a meeting was ever planned—let alone that it happened.

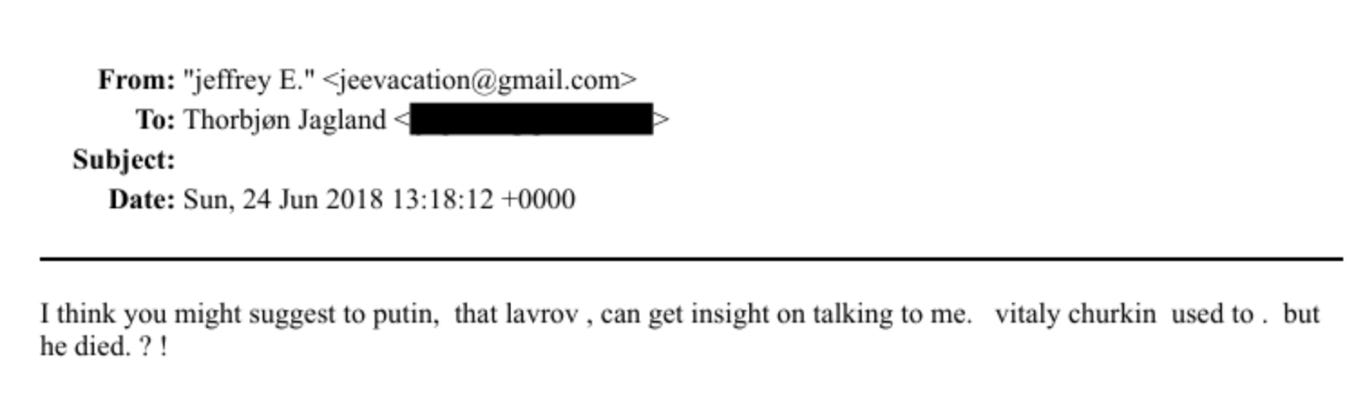

Other emails document Epstein “desperately trying to secure a meeting with Putin,” in the words of the Independent, another British newspaper. Some of those efforts to establish a connection with Putin were made via Thorbjørn Jagland, then–secretary general of the Council of Europe (and prime minister of Norway more than twenty years earlier). In a June 2018 message, Epstein wrote to Jagland to offer his insights to Putin and by extension to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov:

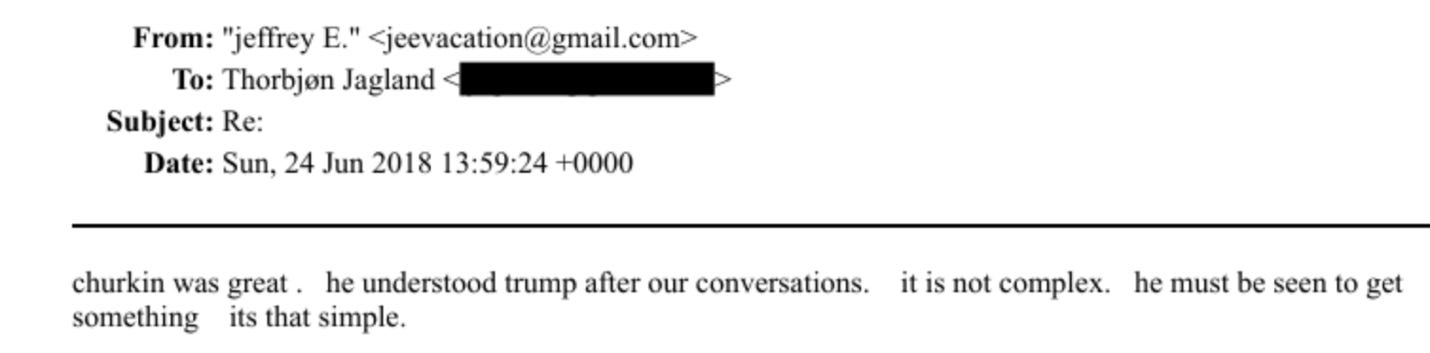

In his reply, Jagland promised to bring this up in a meeting with Lavrov’s assistant. Epstein responded with details about conversations he’d had with Vitaly Churkin, who had been Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations until his death the year before:

It is tempting to read something sinister into Epstein’s remark about how Churkin “understood Trump” after talking with Epstein—the mind immediately turns to the possibility of sexual kompromat—but it could have meant simply that Epstein had offered a fairly commonplace understanding of Trump’s transactional psychology based on his past interactions with the man.1

There is also an FBI document from 2017 recording a claim by a “confidential human source” that “Epstein was President Vladimir Putin’s wealth manager and provided the same service for Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe.” But these are, once again, uncorroborated and unvetted assertions.

PUTIN ASIDE, EPSTEIN’S ASSOCIATIONS with several other Russian figures are worth discussing, starting with Sergei Belyakov. As previously mentioned, he served under Putin as Russia’s deputy minister of economic development; after criticizing government policies in 2014, he was removed from that job and briefly served as chair of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) Foundation, Russia’s answer to Davos.2 His relationship with Epstein antedates his time in government, continued while he was in office, and was kept up as he went on to hold high-level positions with Russian entities that focus on public-private partnerships and foreign investments.

Here’s some of what we know about Epstein’s relationship with Belyakov:

The two men met in person several times over the years.

Belyakov arranged for Epstein to get a Russian travel visa twice, in 2011 and in 2018, though it appears that Epstein did not travel to Russia either time. (In 2011, he canceled a plan to go to Moscow and traveled to Paris instead.)

Belyakov put Epstein in touch with Russian finance and banking officials; Epstein introduced Belyakov to right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel.

Epstein once asked Belyakov for help in squelching an alleged extortion attempt by a Russian model against a close Epstein associate, billionaire investment manager Leon Black. Belyakov promptly sent Epstein a file on the woman.3

Here’s another interesting wrinkle picked up by the independent Russian-language outlet Novaya Gazeta Europe: Epstein’s 2011 business visa application stated that he would be traveling to Russia at the invitation of a nonprofit called Vympel (“pennant” or “banner”). Novaya Gazeta identifies Vympel as an association for veterans of a counterterrorism unit of the FSB, Russia’s state security service and the KGB’s successor. On the other hand, Russia analyst Catherine Fitzpatrick has argued that the outfit mentioned in Epstein’s visa application is a different Vympel—there are, apparently, “a dozen Vympels in Moscow.” Fitzpatrick sees “plenty of [Russian] fingerprints on Epstein,” but also points out that would make no sense for Russian intelligence to “blow [its] cover” by openly using an FSB-affiliated organization, rather than one of its many front groups, as the sponsor of his trip to Russia.

We do know, however, that Belyakov himself has ties to the FSB: In fact, he is a 1998 graduate of the FSB Academy—meaning that he was trained alongside many Russian spies. It doesn’t mean that Belyakov was himself was ever a spy, let alone that he was Epstein’s FSB handler. The world of Russian business is saturated with individuals who have past or present FSB affiliations—and some would say that such connections are never really past. But this background certainly raises additional questions about his relationship with Epstein.

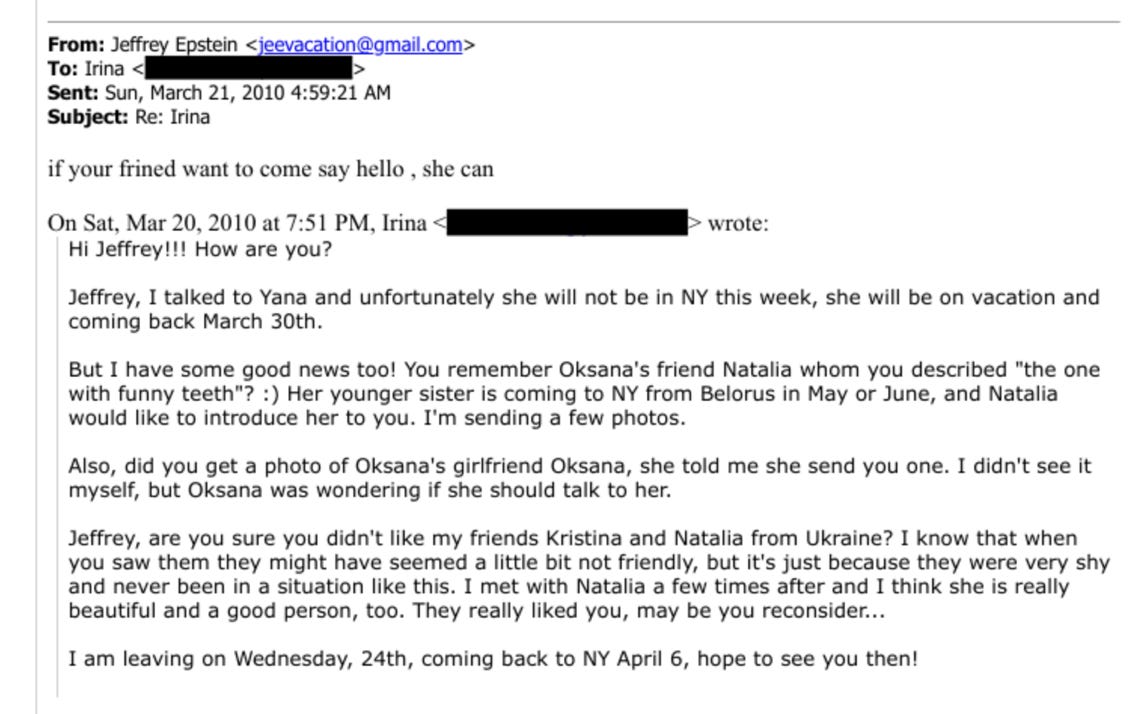

THE NEW FILES shed a bit more light on how Epstein used intermediaries to ensure a steady supply of young women from Russia (as well as Ukraine and Belarus) for his sex-and-party circuit.4 A Krasnodar-based modeling agency called Shtorm is mentioned in relation to getting work in the United States for a model named Raya—something vehemently disputed by Shtorm owner Dana Borisenko. A woman known only as Irina, whose full identity remains unknown, figures prominently in the files as a supplier of Russian and Ukrainian “Epstein girls.”

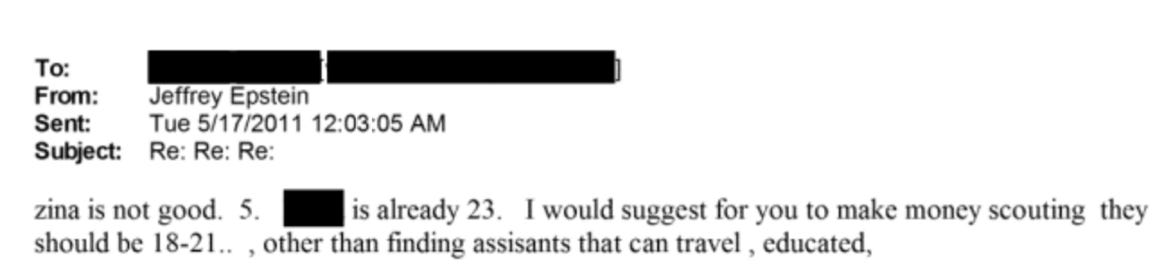

Epstein had a much more prolific supplier in Victoria Spiridonova (now Victoria Ginzburg), the daughter of a prominent Russian businessman and politician. She now lives in France and is a jewelry designer for Dior. In the early 2010s, Spiridonova was associated with the Elite World Group modeling agency and frequently recommended young Russian women to Epstein and sent him photos. Notably, in a 2011 email early in their acquaintance, she asked Epstein what he was looking for: “assistant? direct casting? or escort? all types exist but i need to know clear what you wish.” As far as we know, there is no record of Epstein ever answering the question. He did, however, insist on youth: One email complained that the model referred by Spiridonova was an over-the-hill 23.

This relationship continued at least until 2018, when Epstein wrote to Spiridonova that he was “interviewing new assistants age 20-24” and she offered to help. “Find me three canditades [sic] and we can see,” Epstein wrote back.

But Epstein’s most intriguing Russian connection may be a woman named Maria “Masha” Drokova, first introduced to him by an unknown source in March 2017 as a “wonderlady” who “will be glad to meet you and show you her current plan to conquer the world.”

Before she came to the United States, Drokova first appeared on the public scene at the age of 16 as a teenage leader in the “patriotic” Russian youth movement Nashi (the word means something like “Our People”), launched in 2005 with state-backed financing to form a cadre of pro-Kremlin youth activists. Drokova gained particular fame for a 2009 episode in which she kissed Putin on the cheek, supposedly in a spontaneous outburst of emotion, during his visit to a Nashi summer camp. But around the same time, she began to distance herself from the movement after developing friendships with opposition figures—and especially after one of her new friends, blogger Oleg Kashin, was brutally beaten in apparent retaliation for his activism.

Drokova’s journey away from Nashi—documented in a 2012 Danish documentary called Putin’s Kiss—won her some important liberal friends. In 2015, her entry to the United States on a so-called “Einstein visa,” reserved for immigrants of extraordinary ability, was cosponsored by tech investor Esther Dyson5 and former U.S. ambassador to Russia and vocal Putin opponent Michael McFaul. Drokova’s new role as a tech startup investor in San Francisco became the subject of a glowing profile in the Wall Street Journal in May 2017—days before she first emailed Epstein with a pitch for rehabilitating his image in the #MeToo age.

Drokova’s connection to Epstein was first explored by investigative journalist Seth Hettena in 2021. Drokova, who spoke to Hettena at the time, minimized this connection and asserted that she merely “did some PR work for Epstein as a favor but was never paid by him.” (Henna believes that she was the likely recipient of Deutsche Bank payments from Epstein marked as going to a “Russian publicity agent”; Drokova told him it was a different publicity agent whom she couldn’t safely name.)

In fact, as the Epstein files show, Drokova actively offered Epstein her public-relations services. Her proposed strategies included writing an autobiography (“If you tell more details about how you started and struggled . . . it will make audience like you”), sponsoring a documentary about Epstein’s philanthropy and support for science (“This can also be done as [if] it’s been secretly filmed and you didn’t know it”), and recruiting his friends in the science community to speak on his behalf (“I didn’t see them supporting you in media during the scandal and I think this should be improved”). Also: going on Instagram and YouTube and “supporting gender equality organizations/leaders empowering women.”

A few months later, Drokova sent Epstein more ideas, such as getting the director of Putin’s Kiss, Danish filmmaker Lise Birk Pedersen, to direct an Epstein documentary, or maybe having someone do a Jeffrey Epstein feature film. (The mind boggles.) She also suggested an annual “Epstein Prize” in science (“If you make it bigger than Nobel Prize and support with the ceremony where you’ll invite celebrities from different areas”) and an “antiharassment foundation” to offer women “legal support and career advice”:

If you convince 4-5 public figures to join it it’ll create good [sic] and improve image among women. Also you’d have an access to huge pool of ambitious women-fighters. You can recommend best of them to hire to your business partners or even hire for yourself.

It’s not clear in what capacity Drokova envisioned Epstein and his partners hiring those “ambitious women-fighters.” In any case, he apparently never took her up on any of these ideas, but their contacts continued.6 In December 2017, Drokova asked Epstein how she could find out details about the rumored “coming wave of sanctions against tech companies with R&D in Rusia [sic] (basically any, not necessarily affiliated with Ru government).” The following month, she sent him a gushy birthday message complimenting him on his intellect, “humor and charisma” and “big heart,” calling him “one of the brightest modern philosophers and thinkers” and offering to hook him up with a sex guru as a birthday present. (There’s no record of Epstein’s reply.)

Their last chats on Skype and last in-person meeting took place in late June 2019—less than two weeks before Epstein’s final arrest for sexual trafficking of minors. In a bizarre private exchange on Skype, Drokova sent Epstein pictures of herself taken on a recent trip to Paris that she said she couldn’t share on social media. The chat ends with Epstein requesting nudes and Drokova responding, “Next time I’m in Paris!”

In a long piece published last July about Epstein’s Russia connection, French international relations professor and Russia specialist Françoise Thom suggests that Drokova’s defection from Nashi was faked—that it was a ploy to send her to the United States as an infiltrator to help funnel Russian money into Silicon Valley tech ventures. Some of Thom’s evidence is tenuous and speculative. However, in December 2022, Drokova was mentioned (under her married name, Bucher) in a Washington Post report on expatriate Russian investors who were being investigated for possible participation in “a covert effort to aid their native country in developing cutting-edge technologies such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence.” It does not appear that anything ever came of those inquiries.

Is Drokova—who gave up her Russian citizenship in 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, likely at least in part to avoid sanctions—still a Kremlin loyalist and a canny infiltrator? Hettena notes the curious fact that her former Russian boss, pro-Kremlin blogger Konstantin Rykov, defended her against charges of being a “traitor” to Russia in a social media post in March 2017, noting that “she doesn’t rant, she creates” and asserting that she was helping “several Russian start-ups” thanks to being “integrated into American business.”

Would Rykov (who, for what it’s worth, was actively implicated in Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election) publicly identify Drokova as essentially pro-Russian if she was, in fact, a Kremlin infiltrator? A “hiding in plain sight” tactic cannot be ruled out. But, of course, it’s also possible that Drokova is not a Russian agent but a canny grifter. Hettena notes that among her efforts was a project, reported in 2018, to boost business productivity by helping entrepreneurs “fall in love,” setting them up on dates, or even sending them to “sexual energy retreats.”

Drokova’s relationship with Epstein was also explored in a segment on the Epstein files’ “Russian trail” on the exiled Russian media outlet, TV-Rain. It poses that Drokova’s Nashi background is circumstantial evidence of an Epstein-connected honeytrap operation, since Nashi has been accused of dabbling in such activities: The group is believed to have been behind a 2010 scandal in which several Russian opposition figures were lured into sexual encounters that were secretly filmed and later publicized. Two years later, there were also credible reports from independent Russian media—which still existed at the time—that Nashi founder Vasily Yakemenko had been using the organization to recruit young women for sex work.

Even so, none of this leads directly to Drokova herself, and nothing in the Epstein files—so far—indicates that she played such a role.

ULTIMATELY, AT LEAST SO FAR, the available information on Epstein’s ties to Russia is infinitely frustrating. Some, like Françoise Thom, connect enough dots to be convinced that Epstein was at the center of a major, intricate, multiyear FSB honeytrap operation. (Thom even sees an additional clue in Epstein’s association with Ghislaine Maxwell, whose father, the late media tycoon Robert Maxwell, was openly Soviet-friendly and suspected of ties to the KGB.)7 Others see a shady finance operator and sexual predator who had a number of equally shady Russian characters in his orbit, some of them involved in the sexual trafficking of young women from Russia and other former Soviet republics—but with no proof of an intelligence angle.

“Everyone sees what they wants in those files,” Russian émigré political analyst Stanislav Belkovsky said in a YouTube interview, pointing out that “many Kremlin-adjacent commentators” have focused on a one-line comment in Epstein’s email to banker Ariane de Rothschild shortly after the February 2014 “Revolution of Dignity” in Ukraine observing that “ukraine upheaval should provide many opportunites [sic].” To Belkovsky, the files suggest that Epstein “was a collector of various contacts, communications, and names in order to pass himself off as someone he wasn’t”—that is, as an influential player in world affairs. TV-Rain analyst Mikhail Fishman also concludes that, while a lot of Epstein’s Russian contacts raise suspicions, attempts to connect those dots, so far, yield no definitive proof of a Kremlin connection.

Not all the Epstein files have been disclosed, and the portion still to come may reveal new surprises. But it is worth noting that no U.S. intelligence sources to date, as far as we know, have flagged Epstein as a supplier of information to Russian intelligence. And, while the files certainly suggest that Epstein was compiling real or concocted blackmail material on his associates including Microsoft founder Bill Gates, there is no evidence that any of that material ended up in Russian hands.

Eventually, we may learn more—perhaps from the Polish probe mentioned by Tusk. Tracking the full extent and significance of Epstein’s Russia connections is certainly important. But it’s no less important to use the truth as a beacon of light so as not to fall so far down a conspiracy-theory rabbit hole that you can’t see your way out.

The correspondence involving Jagland and Epstein is not from the latest batch of Epstein files but from a previous tranche of documents released in November. (Churkin, though, does also figure in the latest Epstein releases: There’s a 2016 text message thread in which he and Epstein discuss finding a job for Churkin’s son Maxim.)

Another key figure in SPIEFF is Kirill Dmitriev, Putin’s special envoy for the Ukraine negotiations during Trump’s second term.

The model, Guzel Ganieva, would go on to sue for Leon Black for sexual abuse while he sued her, and the law firm then representing her, for extortion. As chronicled in a 2024 Puck News report, it was an extremely convoluted and messy case, with still-ongoing litigation.

The trafficking of women from that region for sexual exploitation has been identified as a big problem since the 1990s.

Esther Dyson has been characterized as being “buddies” with Epstein, but that appears to be extrapolated from very limited interactions.

In December 2017, Drokova shared with Epstein some thoughts on how smart people can be selected by genetic testing for Jewish origins: “The more Jew you are, the smarter you are.”

Maxwell père, who died in a boating accident (or suicide) in 1991, was also alleged to have worked with British intelligence and Israel’s Mossad.