Meet Me in the Middle of the Air

A mischievous history of miracles during the early modern period pokes at our most basic assumptions about life, the universe, and everything.

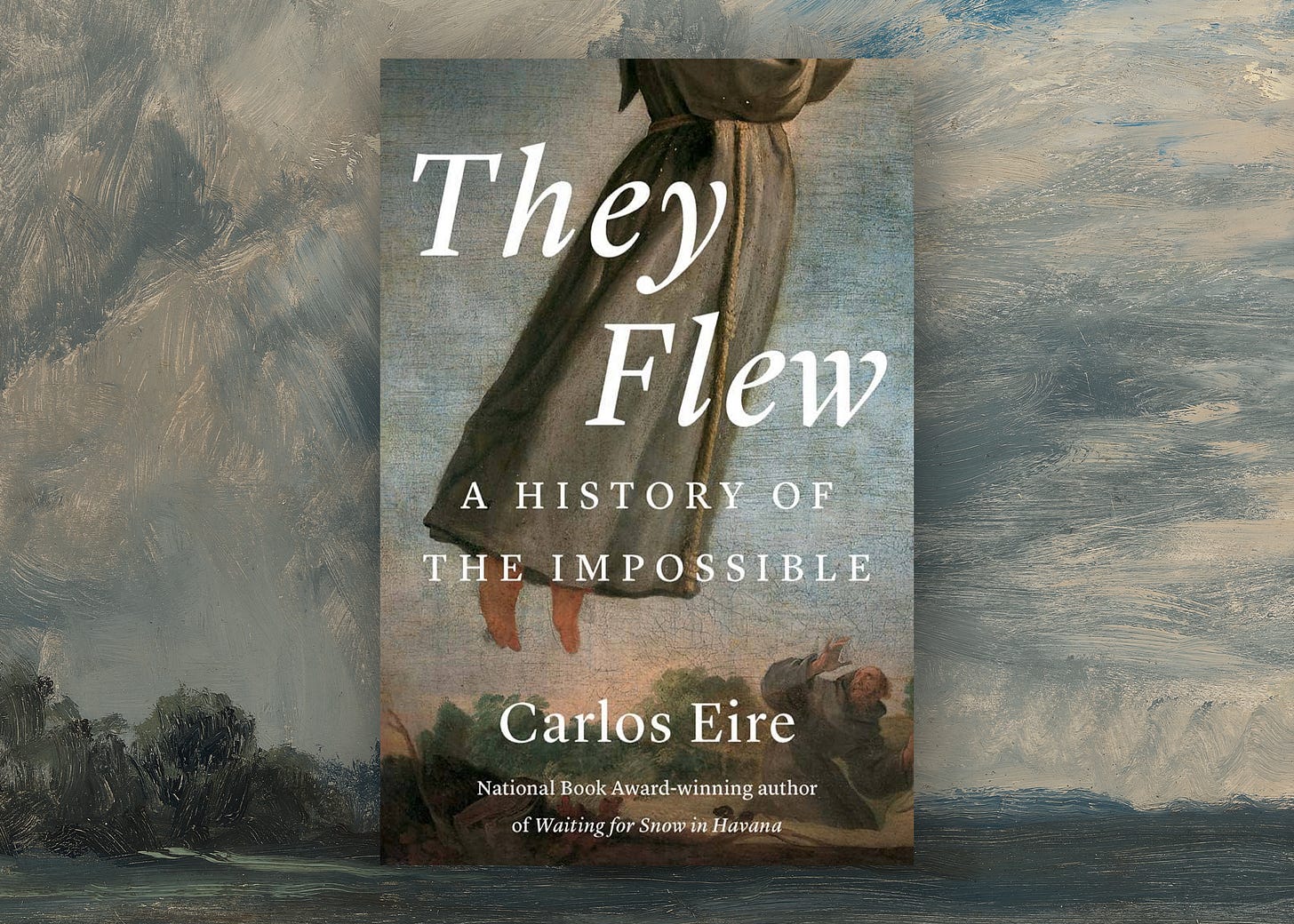

They Flew

A History of the Impossible

by Carlos Eire

Yale, 512 pp., $35

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, THE MAKERS OF PUBLIC CULTURE in this country conspired to persuade me that people can’t fly. They did this by showing me flying people. After school I’d watch The Greatest American Hero on ABC, whose theme song (“Believe it or not—I’m walking on air!”) taught me that walking on air was incredible. Virginia Hamilton’s beloved collection of black folktales, The People Could Fly, taught me that flying was a vanished gift of other people’s ancestors. And every kid knew the advertising slogan for the 1978 Superman film, which promised the impossible: “You’ll believe a man can fly!”

In all these ways, I and every other American learned that people don’t fly—not in nonfiction, not in the publicly authorized reality of history textbooks and evening news. But the propaganda didn’t work. On the first page of Yale history professor Carlos Eire’s puckish new study of levitating and bilocating saints, frauds, and witches in the early modern era, which has the perfectly provocative title They Flew, he writes that it’s “absolutely impossible” for people to fly without the aid of technology, “and everyone can agree on this, for certain. Or at least everyone nowadays who doesn’t want to be taken for a fool or an unhinged eccentric.” Reading this line, I thought, What are you talking about? I doubt you could stand in any major urban center in this country and be more than a mile from somebody who believes that some people fly. Catholics believe that St. Teresa of Ávila floated; some Buddhists make similar claims for the Buddha; I’m in California right now and I guarantee somebody within a mile of me thinks you can fly if you line up your crystals just right and flap your arms.

Eire’s book is about the specific lives of, and wild claims made about, people in the early modern period, roughly spanning the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries. But it’s also about a hidden culture within modernity and postmodernity: Contemporary thought and experience is riddled with premodern belief. Then, too, the way we think of “premodern faith” borrows much from counter-movements against modern rationality, like Romanticism and postmodernism. (Eire notes that the terms “bilocation”—the ability to be in two places at once—and “levitation,” now used to describe the supernatural activities of Catholic saints, were popularized by nineteenth-century spiritualists.) And any responsible account of the coming of modernity must explore the fact that the Age of Reason was also an age of rampant miracles, escalating claims for the power of Satan, and witch hunts. Eire takes a chop-licking pleasure in recounting the feats of St. Salvador de Orta, who “rose up in ecstasy . . . and remained suspended in the air” when confronted with the beauty of a pomegranate; the transoceanic bilocation and political power of María de Ágreda; and the exquisitely detailed taxonomies of the netherworld crafted by early German Protestants. But he’s also here to question our assumptions about rationality and possibility.

The early modern era was a boom time for claims of miraculous flight and bilocation. Catholics, especially in the Iberian peninsula, went miracle-mad—miracles were the best anti-Protestant polemic. Eire hints that the printing press may have played a role in what he calls the “Catholic Inflationary Spiral” in which “credulity was strained by the sheer volume of miracle accounts.” The possibility of fads in the spiritual life might give a reader pause. Does God really decide, Okay, it’s been a while since I got on a miracle kick, maybe I’ll let them fly around now? Did God wait until the Middle Ages to invent the stigmata, or did we do that?

Eire is alive to all the reasons to be skeptical. He has a true historian’s love of the unsettling, anti-ideological qualities of the past. He is not interested in discovering an edifying past—a useful past. But he is also willing to wonder. He notes that many of the miracles he describes were witnessed outdoors (thus with little possibility of concealing some sort of support pole or other trickery) by crowds of people from all walks of life. Levitation is about as well-attested as any early modern phenomenon can be. Those who wish to explain away these reports often find themselves resorting to theories about mass hallucination or other forms of historical cope.

Which only leaves us with more questions. If this stuff happened—if they flew—how and why? If it was God, what was the point of it all? Just to draw attention to this one saint? To win arguments with heretics? Where is God’s love in these displays of superhuman power? And is it true that Satanists and witches could fly too?

Eire is too much of an ironist to ask these questions directly. But in both the details and the structure of his book, he does suggest some possible answers. (In general, They Flew is suggestive, not declarative.) The first section is dedicated to two canonized saints and one enigma. It describes the physical experience of ecstatic prayer: “a highly paradoxical coincidence of opposites beyond normal human cognition . . . in which . . . pain and bliss, logic and emotion, embodiment and disembodiment, materiality and spirituality, and creature and creator become perfectly and blissfully compatible.” Or, in Teresa of Ávila’s more pungent phrase: “a violent, delectable martyrdom.” Teresa’s helpless encounters with God demonstrate that God loves us in spite of the incapacity of sinful flesh to bear this love.

EIRE’S MODERN AGE is an age of regulation, rationalization, and the interpenetration of doubt and faith. He describes changes to the Catholic Church’s canonization process to invite criticism and skeptical explanations. And Eire discusses the Church’s intense emphasis on obedience as a marker of true rather than feigned sanctity. These flying saints are often disgraced, humiliated, even imprisoned by Church authorities. Their obedience to their superiors is tested again and again. This obedience is treated as proof of their humility and, therefore, their holiness. It is through obedience that they triumph—if, in some cases, only after death—over the hierarchs who doubted or despised them.

The second section looks at three disgraced nuns. One confessed to being a fraud, another to being a consort of the Devil; the third was declared innocent by the Inquisition, but the cloud of suspicion around her name has not dispersed. In an age of war, agonizing religious division, plague, and famine, the people around any would-be saint were desperate to believe and adore and follow. Nuns who were believed to work wonders could wield great political influence from behind their convent walls, advising the embattled Catholic nobility by correspondence. Perhaps humility was such a marker of sanctity because pride was such a strong temptation. Eire has the least sympathy for Magdalena de la Cruz, who tyrannized her nuns while claiming sinlessness, and the most for Luisa de la Ascensión, who died in penitential seclusion.

At last Eire turns to the witch craze of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Witch-hunting was a pastime shared by Catholic and Protestant polities—but on both sides of the Reformation, it was controversial. Those who believed witches to be powerful and ubiquitous borrowed arguments from people they would consider heretics or idolators in other contexts; and those who opposed the witch-hunts also echoed witch-skeptics on the other side of the confessional divide.

Eire is a witchsymp. Who wouldn’t be? He describes the totalitarian, hysterical atmosphere of towns in the grip of a witch hunt: the spiral of neighbor accusing neighbor under torture. He offers, without unnecessary comment, the justification given by one French Catholic jurist for suspending ordinary rules of evidence and civil procedure: “The proof of such crimes is so obscure and so difficult that not one witch in a million would be accused or punished” if we stuck to the rules.

But here, too, Eire has metaphysical points to make in addition to his political and emotional ones. He notes that Protestants did not disagree that some people could fly. (This inelastic factlike nature of the flights seems important!) But as the Reformers rid Christian life of sacraments and relics and many ascetic practices, they taught Christians to live in a material world that was sharply distinct from the spiritual. Protestantism emphasized God’s otherness, whereas Catholicism held that the spiritual world continues to pierce and shake and permeate the earthly realm. This penetration might be predictable, as in the celebration of the Mass, or it might be capricious and even weird. I pray with a saint-of-the-day calendar every morning, and it has this to say about one of today’s saints, the fifteenth century’s Catherine of Genoa: “In addition to her body remaining undecomposed and one of her arms elongating in a peculiar manner shortly before her death, the blood from her stigmata gave off exceptional heat.”

Reformation-era Protestants argued that you do not have to wonder at a long-armed lady. “The miracles mentioned in the Bible had really occurred, [Protestants] argued, but such marvels became unnecessary after the birth of the early church and would never, ever happen again,” as Eire puts it. But if God no longer works miracles, then superhuman abilities—such as the levitations that, again, everybody agreed actually happened—must be the work of the Devil.

Eire charts the rising prominence of the Devil on the Protestant side, a kind of “Devil of the gaps” whose evil power explained whatever might previously have been counted mysterious or holy. Modernity made Catholics, too, more Devil-conscious. Catholics didn’t simply reject modernity and retrench. They accepted ideas of scientific rigor and rational faith. Many folk practices that had once been considered harmless, medicinal, or even pious were now examined and declared to be irrational and unjustified: forms of magic, even forms of diabolism.

Miracles crept back into Protestantism over time. Eire highlights recently discovered writing by Jonathan Edwards’s wife, Sarah. This American Protestant matriarch describes the ecstasy of her mystical prayer. Maybe she’s speaking metaphorically when she talks about being drawn upward—she repeats “as it were” in these descriptions: “I could not help as it were flying out of my chair without being held down.” But perhaps mystical union with God is as persistent a phenomenon as hovering humans.

Most early modern Europeans (and settlers in the Americas) were convinced that some people could fly. The only question was how they did it. Eire notes that his own profession generally excludes this question: Respectable history has no place for God, let alone the Devil, as a historical actor. Historians sometimes claim that they are only interested in how belief functioned in society, not whether the beliefs were true or false. Eire’s fascinating, provocative epilogue quotes Rice University professor Jeffrey Kripal’s astonished ridicule of this historiographical pose:

Uh, excuse me, if [the levitations of St. Joseph of Cupertino and St. Teresa of Ávila] actually happened (and our historical records suggest strongly that they did), such anomalous events change pretty much everything we thought we knew about human consciousness and its relationship to physics, gravity, and material reality. . . . And you don’t care? Don’t you find that disinterest just a little bit perverse?

If you have spoken in tongues, or seen visions, you are forced to care about the origin of these shattering experiences. If you have not experienced such obvious disruptions of secular-consensus reality, you may find yourself wondering why people think God would do such weird, hard-to-interpret things. Or, if you are a believer, you may find yourself wondering why God has done such weird things, but only for other people. When it is personal, both supernatural encounters and the lack of them can be described with wonder and humility.

But when it’s theoretical, Christians face the temptation to proclaim belief in miracles as a marker of tribal allegiance, a way of crafting our personas and shoring up our egos. The more extreme and ridiculous the miracle tale, the more believing it proves that we’re “hardcore.” I absolutely believe that St. Catherine had hot stigmata. You see how it works?

It’s easy to say They flew! out of sinful pride. It’s to Carlos Eire’s credit that his book is shaped more like a proposal: an invitation to imagine a weirder world.