The Practical Perils of Overclassification

The U.S. government’s outdated system for protecting the nation’s secrets has unnecessary operational costs.

IT SEEMS LIKE EVERY WEEK brings news of someone caught stealing, sharing, or mishandling classified information. Sometimes it’s even more often than that: On March 2, David Slater, an Air Force civilian employee and retired Army lieutenant colonel, was arrested and charged with three counts of transmitting classified information via a foreign online dating service. Two days later, Jack Teixeira, a Massachusetts Air National Guardsman, pleaded guilty to six counts of willfully retaining and disseminating national defense information through the social media platform Discord. Three days after that, Sgt. Korbein Schultz, an Army intelligence analyst, was arrested and charged with six counts, including conspiracy to disclose national security information to a foreign national.

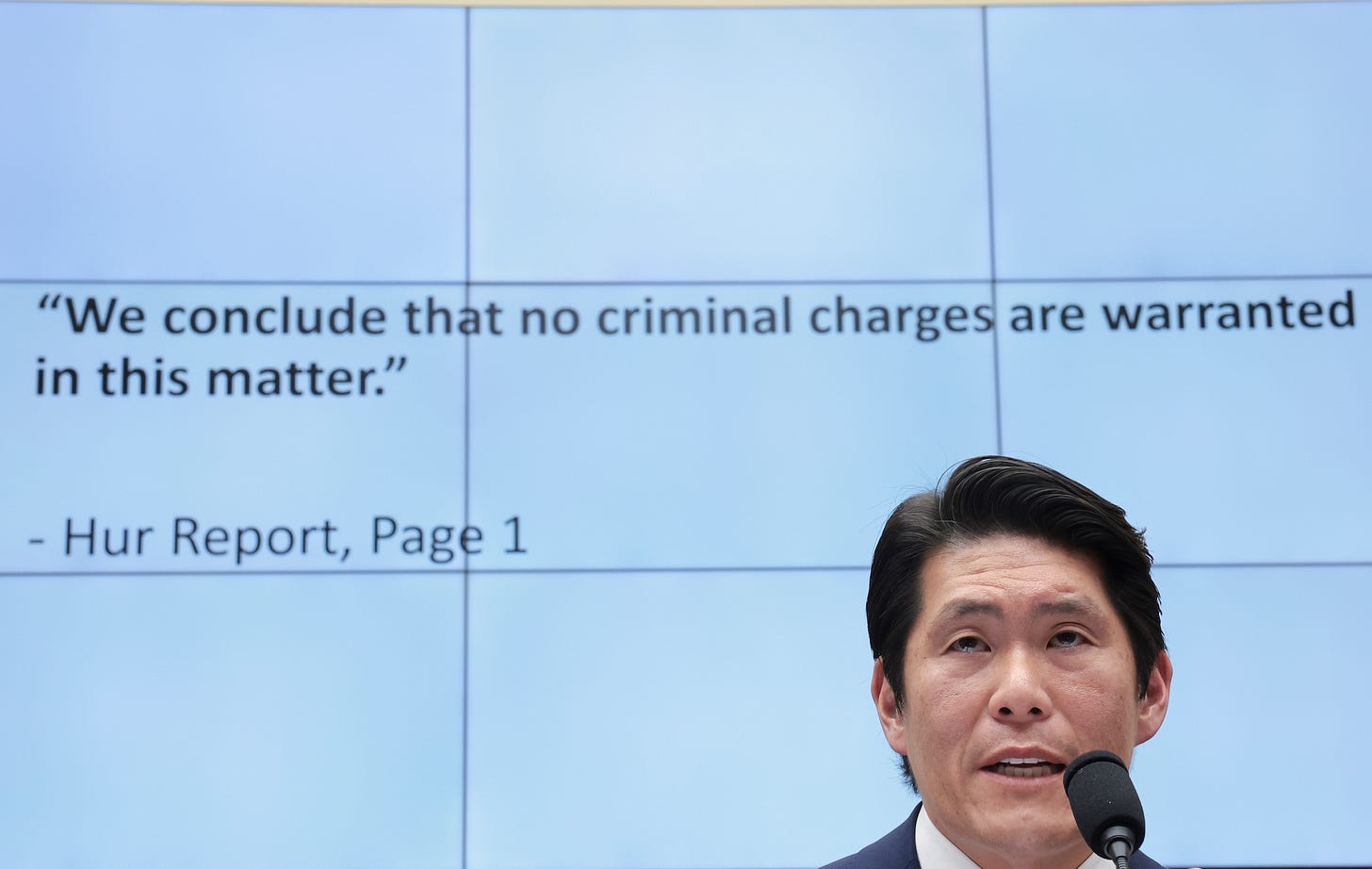

This problem isn’t confined to low- and mid-level national security officials like Slater, Teixeira, and Schultz. For the third straight presidential election, both major-party nominees have been investigated for—at the very least—willfully mishandling classified information. To be clear, the cases involving Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden are all very different, and Trump’s case appears to be the most egregious—but collectively, they illustrate the problem we have with classified information.

Each of these people had his or her own reasons and explanations for breaking the rules. Amn. Teixeira wanted to impress his friends. Sgt. Schultz was allegedly paid $42,000 for his information. Slater was likely lured into a honeypot. Clinton and Biden blamed their subordinates for inadvertently mishandling documents. Trump—well, that’s anyone’s guess, and motive may become a key part of his trial (if he ever has one).

All these cases stem from one overarching problem: overclassification. The national security state’s penchant to classify nearly every piece of information—even branding certain unclassified information as “controlled unclassified information”—all but guarantees that people will mishandle documents. More classified information means more Americans need security clearances to handle a deluge of classified documents. The process by which people are cleared is anachronistic and ill suited to detect insider threats in the information age. Until something changes, our adversaries will continue to exploit these vulnerabilities.

DURING WORLD WAR II, when the modern American intelligence and national security state got its start, the mantra was “Loose lips sink ships.” These days it might be something more like “Secret secrets are no fun unless you tell everyone.” More than four million Americans have security clearances, including 1.3 million with top-secret clearances. A staggering 1.5 percent of the U.S. population has access to classified information. Which suggests that the information isn’t all that secret.

Every year the government generates 50 million classified documents. In 2012, the federal government warned that it was classifying a million gigabytes annually. Now it’s classifying the same amount every month. If all that data were in Microsoft Word documents, it would surpass 500 billion pages. Printed out and laid side by side, that would be enough paper to completely cover Maryland, with a good deal left over.1 Every month.

Why does this happen?

With the explosion of digital information, the same rules that once applied only to printed pages are being applied to a databases, videos, audio, images, and a host of other media. For overworked government employees awash in an abundance of information, it’s prudent to overclassify. There are basically no penalties for doing so, while the penalties for improperly disseminating classified information can be severe. When I was an intelligence officer, I was part of the problem: I never took disciplinary action against one of my service members for overclassifying documents, but I did against those who mishandled them, even if it was inadvertent. That’s just how the system worked.

When every document is classified, nothing is classified. As President Barack Obama famously quipped, “There’s classified, and then there’s classified. . . . There’s stuff that is top-secret, top-secret, and there’s stuff being presented . . . that you could get in open source.” In essence, security officials who safeguard the nation’s secrets often protect information so trivial, mundane, or commonplace that you could find it with a quick Google search.

Overclassification leads to even more absurd situations. During my first deployment to Baghdad, nearly every operation center had maps with the city’s route names, which were technically classified. Yet every journalist and Iraqi knew that “Route Irish” was the deadliest road in Baghdad. Even some of the Iraqi police centers had “classified” maps on their walls. Similarly, the details of every firefight I was in during my six deployments were labeled “secret” even though we often had reporters in our vehicles. There are strict guidelines for carrying classified documents, but everyone downrange holds them in their own “classified storage container”—their right pants pocket.

THE PROBLEM OF OVERCLASSIFICATION isn’t just about government waste or inefficiency. During my training for my last deployment to Afghanistan, a general officer from an allied nation spent nearly an hour scolding my class because he was frustrated with America’s classification system. I don’t blame him. Working with Americans can be maddening. I’ve seen allies asked to leave a briefing room so the briefer could name a suicide bomber that killed their troops.

Overclassification exacts a cost on American service members as well. My airmen worried constantly about losing their clearances, so they didn’t share their stressors and troubles with their families. I often counseled them to leave the details out of their stories, but if your family’s livelihood was potentially on the line, would you take the chance? It is little wonder that the military has the highest divorce rate of any career field in America.

Because nearly everyone has a clearance, agencies build more barriers to prevent widespread access to top-secret information. Some agencies require a polygraph, even though it has long been established that polygraphs do not accurately detect lies. Other agencies construct special access programs (SAPs) to keep a tighter lid on things. SAPs must be where the real secret information is hidden, right? Nope. Some are worthwhile, but not all of them. At the twilight of my career, I intentionally declined to be read into them because they weren’t worth the hassle.

Compounding the overclassification problem is the background investigation process by which people are cleared to handle government secrets. Nearly every agency requires applicants to fill out the dreaded SF-86, a detailed questionnaire that investigators use to look for possible vulnerabilities in our background, which they then investigate. It’s also outdated: Despite the questionnaire’s length, it does not ask applicants for their social media information—nothing about Facebook, Twitter, or Discord, as Teixeira can attest.

Some would likely lie even if the SF-86 asked applicants for this information. The SF-86 partly relies on the applicant’s integrity. For example, applicants must list every “close and continuing” foreign contact. But if they don’t, will overworked investigators stumble upon them? Although there have been some notable reforms, the amount of information on the questionnaire ensures that investigators will miss red flags. This likely partly explains how investigators missed Teixeira’s extensive history of violent and racist remarks to his high school classmates. He should never have had a top-secret clearance in the first place, but the Air Force is in a recruiting crisis and needs information-technology specialists like Teixeira to handle a never-ending array of classified networks.

The Air Force disciplined Teixeira’s leadership for missing warning signs and temporarily removed his wing’s mission. The service also enacted stand-down training on classified information. I participated in this training, and it was painful. Imagine an all-day PowerPoint presentation about how you could lose your job if you don’t memorize the tax code. Most service members understand they cannot disclose classified information. The problem is that too much stuff is classified, and too many people have access to truly sensitive information.

THERE ARE WAYS TO ALLEVIATE the problem. According to Henry Sokolski of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, the government has about 2,000 security classification guidebooks and roughly 1,400 original classification authorities—that is, people who have the power to declare information classified in the first place (which therefore also classifies anything derived from or including that information at the same level or higher). To streamline the effort, the Biden administration should accelerate updating the fifteen-year-old executive order governing classification. By simplifying and making the guidelines more accessible, public servants would be less likely to press the easy button and overclassify every document.

Congress could also lend a helping hand. The Public Interest Declassification Board, created nearly two decades ago to advise the president on these matters, lacks proper funding; Congress should fix that problem.

Agencies could also incentivize their employees not to overclassify documents. In my last year in Afghanistan, my agency evaluated its deployed employees by their ability to write reports at the lowest classification level possible to ensure our allies received our intelligence. It was the perfect incentive. I intentionally wrote reports so our allies could access them, which they greatly appreciated.

Overclassification is not a new or underappreciated issue. Avril Haines, the director of national intelligence, stated back in 2022 that the opacity and obsolescence of the current system is a “threat to our national security.” While foreign intelligence services will always remain a national security threat, classifying every document treats mundane information the same as the identity of clandestine sources. It overburdens an already stretched workforce and places too much emphasis on reviewing documents instead of identifying threats. And it creates difficulties in our relations with trusted allies, keeping them at arm’s length despite their commitments on the battlefield.

Until the federal government enacts much-needed reforms, our nation’s most valued secrets—the ones that could lead to a loss of blood and treasure—will remain unnecessarily vulnerable.

A gigabyte of storage fits 524,288 pages of Word files, give or take. If each page is a standard 8.5x11 sheet, then the total area covered by 500 billion sheets would be more than 46 trillion square inches, or about 11,644 square miles. The total land area of Maryland in 9,707 square miles.