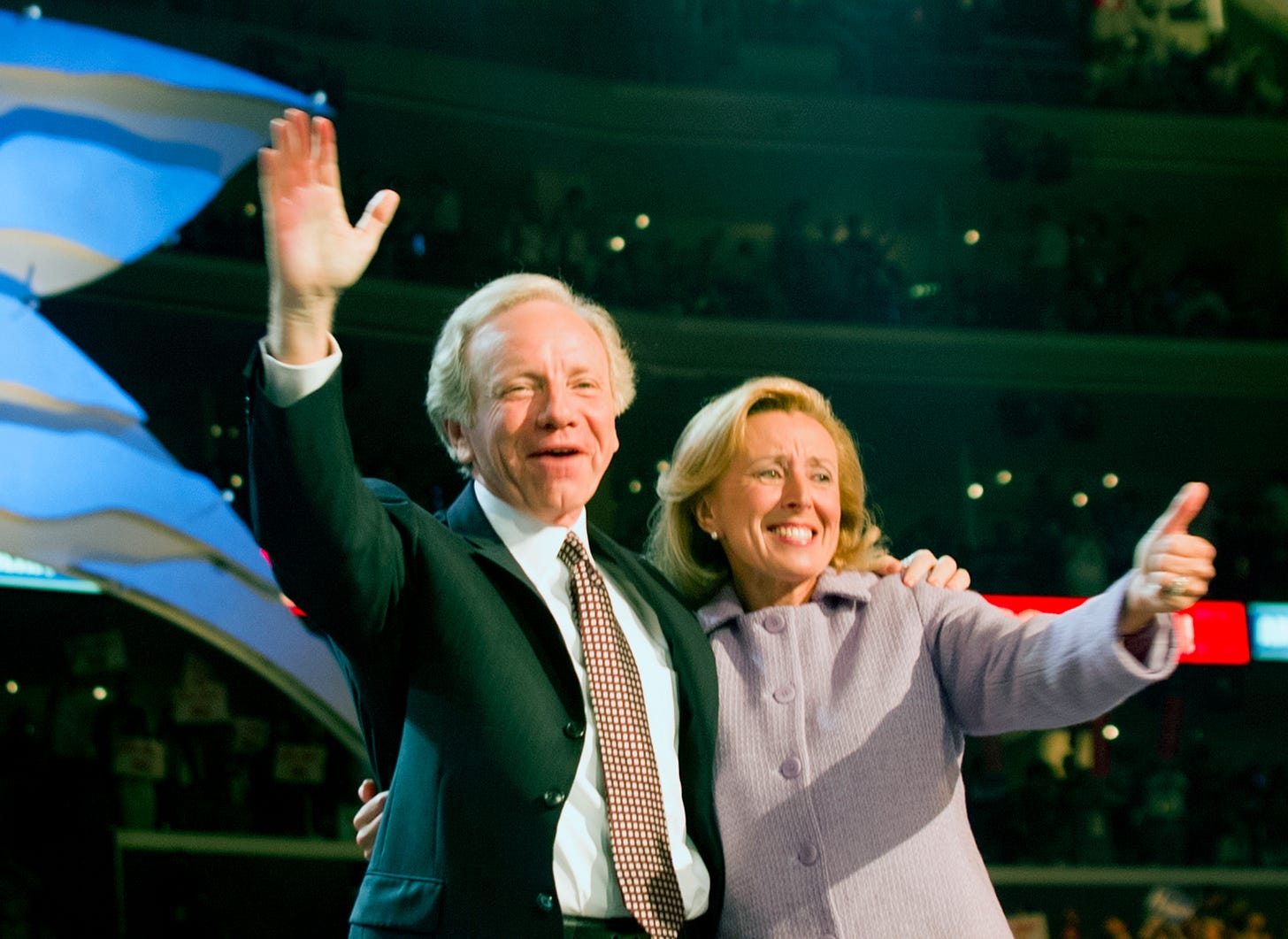

Joseph Lieberman, four-term U.S. senator and Democratic vice presidential nominee, died yesterday at the age of 82.

Happy Thursday.

Joseph I. Lieberman, 1942-2024

A public servant of principle and decency, an American patriot and a proud Jew, a happy warrior and a kind man, Joe Lieberman was an example and an inspiration to us all.

It is an honor and privilege to have known him.

I emailed condolences last night to a couple of former staffers who were close to him. One—a Washington veteran who’s seen it all, not given to effusiveness or sentimentality—wrote back: “He was the epitome of decency and integrity. I really loved the man.”

I thought that I might be able to convey something about Joe Lieberman the man, something of the flavor of his personality and character, by reproducing a few excerpts from a “Conversation” I had with him in late 2014. You can watch or listen to the conversation here, or read the full transcript here.

KRISTOL:

I’ve looked forward to discussing your long, distinguished, varied, interesting career in public life. Maybe I’ll begin by just asking you, is there one moment that stands out?

LIEBERMAN:

I’ve been lucky. I’ve had a lot of great moments. Really the most memorable moment, I would say, would have to be the opportunity that Al Gore gave me when he asked me to be his running mate in 2000 as vice president . . .

I get a call from the vice president’s office that he’s now interviewing the sort of short list. It was probably five or six people. And in a really ornate process, they told me that a fellow named Philip Dufour, who was sort of the chief of staff at the residence, is going to come and pick me up in a van with tinted windows at my house and drive me in the back way to the vice president’s residence.

So I went in and I had a conversation. And in a way, it was awkward, because Al and I are friends, we were fairly close then. But he really has to interview me, and you know, we went over some of the things. And he too asked me, is there anything about your past that we haven’t found out that I should know because it is going to come out.

It’s just the two of us and no staff, and it was a cordial conversation. I mean I knew him well enough to joke a little bit. And that was it . . .

So this is Sunday night. We know that the decision is being made. I had people sort of close in the Gore campaign who are telling us things. About that evening, my mother had come up from Stanford. She was then about 80, maybe 85, actually. And I get a call from my press secretary. He tells me he’s just heard from somebody at one of the networks and he’s sorry to have to be the one to tell me but they’ve heard from inside that they’ve selected John Edwards. So, I—you know, I pull out a bottle of wine, I bring the family together. I said, you know, “This was incredible that we got this close,” and we have a toast to America and everything, isn’t it wonderful?

And we go to sleep, but the TV trucks are still out there. And I get up in the morning and I flip on the remote at about five to seven—I’m still in bed with Hadassah. And the local TV anchor is saying, “Now, let me just repeat that really exciting news. The AP is reporting that Vice President Gore has chosen our own Senator Joe Lieberman to be his running mate.” What?

KRISTOL:

So you see this on TV before you get a phone call from anyone?

LIEBERMAN:

I didn’t get a phone call. I wake Hadassah up. All hell breaks loose.

I mean, if you want a little local color. One of my few jobs, as Hadassah would tell you, in the house is I make the coffee in the morning. So it’s August. I’m in my underwear. So I walk down into the kitchen to make the coffee and there are TV cameras at each of the windows. So I go hit the floor . . .

[That evening] we had a lovely dinner, the Gore family and my family. And Al Gore said at that dinner, he said, “I want you to know that I decided two weeks ago that I wanted you to be my running mate, but I really thought it would be irresponsible for me not to try to talk to some other people about whether they thought America was ready for a Jewish Vice President.”

So I always wondered whether Al did a poll. I think if I were him, I would have done a poll. But he said he called a number of friends. And he said to me, “I called a number of my Jewish friends, and I called a number of my Christian friends. And here was what I found. Most of the Jews were extremely anxious and uncertain about the reaction to your nomination.” He said, “Every Christian friend I called said there would be no problem.” So then with a little bit of Gore humor, which people don’t remember sometimes, he said, “So, since I know that there are so millions more Christians in America than Jews, I decided I could choose you, which is what I wanted to do.” Anyway, that was it.

And then it was announced the next morning at the War Memorial Plaza, a big plaza in Nashville. It was thrilling. And Hadassah did something. He asked her to get up and sort of say something. She toasted him at the dinner on Monday night and said you know for her personally, she’s a child of Holocaust survivors, there was really—I get choked up—it was really unbelievable that she was where she was with her husband nominated to be the second highest office in America, the greatest country in the world. And he said to her afterward, you know, “I want you to introduce Joe tomorrow and if you want to say something like that, say it,” and she did, it was really quite moving. It was a great day . . .

So that whole day was really, if you ask people what’s the most thrilling moment, really it was. And even though it ended in the strange way it did, I always say not to re-litigate the results, but you know we did get a half million more votes and it does—it vindicated Gore’s confidence that America was not going to judge me based on my religion. And it’s a wonderful thing to be able to say.

It is a wonderful thing to be able to say, said by a man who lived a wonderful life.

As George W. Bush said last night, one hopes “that Joe’s example of decency guides our nation’s leaders now and into the future.”

May his memory be a blessing.

—William Kristol

What Went Wrong on Dali?

What do you do if a man-made disaster turns out to be nobody’s fault?

That’s a question on our minds in the wake of the destruction of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge, which collapsed early Tuesday morning after a mammoth container ship, the 985-foot Dali, lost control and plowed into one of its main support columns.

Eight workmen were on the bridge at the time; two were rescued, and six are now presumed dead. That the attempts to recover their bodies have so far been fruitless is a grim illustration of just how nasty a logistical problem the collapsed bridge presents—a tangle of twisted metal and concrete rubble submerged in murky water 50 feet deep. They don’t even have the Dali out yet. Pinned under huge trusses from the bridge, with crew unsure whether the ship is safe to navigate even if it were free, the massive vessel could take weeks to move.

Until the channel is cleared—to say nothing of the bridge being reconstructed—the economic damage will be significant. The vast majority of the Port of Baltimore’s shipping facilities are now cut off behind the wreckage of the bridge. Much Baltimore-bound commerce can be routed through other east-coast ports, but that means extra load on already stressed supply chains; meanwhile, according to White House estimates, 8,000 Baltimore longshoremen will be sitting on their hands.

Unsurprisingly, wild conspiracy theories and cheap political posturing proliferated online in the wake of the disaster. The Dali had been cyber-hijacked. It had been crewed by feckless “diversity-hire” personnel thanks to “anti-white business practices.” It was possible that “the wide open border” was involved.

Then there was plenty of armchair speculation that was less self-evidently insane. The Dali had had a smaller-scale accident before; were there warning signs about its reliability? If there were, should the Coast Guard, which is responsible for inspecting shipping vessels, have picked them up? The Key Bridge was nearly 50 years old; if it had been retrofitted to make it more resilient, would it still have collapsed?

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg spent some time gently pushing back on some of these questions at the White House yesterday.

“Is it your view that the bridge was built strongly enough?” a reporter asked Buttigieg. “Why didn’t it have some of the defensive structures around the support column, as many other bridges do?”

“Again, I don’t want to get ahead of any investigation either,” Buttigieg replied. “I will say that a part of what’s being debated is whether any design feature now known would have made a difference in this case.”

That’s an understatement. The Dali isn’t the biggest container ship in the world, but it’s still massive—roughly 150,000 tons while fully loaded—and was moving about 9 mph when it collided with the bridge. There’s plenty of grim back-of-the-envelope ways to give an idea of the sheer awful p=mv momentum needed to stop an object like that. It’s the explosive equivalent of ten 5000-pound bunker-buster bombs. It’s the Statue of Liberty moving at the speed of an ICBM. It’s a lot to ask of a bridge.

Should the ship’s mechanical failure have been foreseeable? It’s too early to say, although you can bet investigators will find out. “It’s likely that virtually every pilot in the country has experienced a power loss of some kind [but] it generally is momentary,” Clay Diamond, executive director of the American Pilots’ Association, told USA Today this week. “This was a complete blackout of all the power on the ship, so that’s unusual. Of course this happened at the worst possible location.”

That’s the bottom line here: How flatly unlucky the Dali was at every turn. The worst possible location to lose power—after the tugs that turned it out to sea had detached, but before it was safely out of the harbor. The worst possible drift once it lost power—whether due to the position of the rudder, or wind, or current—apparently compounded by the ship’s response to the crew throwing it hard astern in a desperate attempt to slow it right before the crash.

Maybe they’ll find a culprit—some human error to pinpoint, some regulatory deficiency to address. But maybe the collapse of the Key Bridge will just prove one tragic and hugely costly demonstration that shipping has risks, and keeping those risks at acceptable levels isn’t the same as getting them to zero.

—Andrew Egger

Catching up . . .

Investigators identify 764 tons of hazardous material on the Dali: Washington Post

Chris Christie turns down running with No Labels: Axios

JD Vance’s VP prospects could rise after he helped deliver Trump a big Ohio win: NBC News

Judge recommends disbarment for John Eastman, architect of Trump’s election plot: MSNBC

The five minutes that brought down the Francis Scott Key bridge: New York Times

‘Shortcuts everywhere’: How Boeing favored speed over quality: New York Times

Kari Lake seeks to forfeit her defense in defamation case: The Hill

Quick Hits

1. Menendez’s Quieter Corruption

Why is indicted Sen. Bob Menendez still behaving as though he’s running for re-election? Unlike also-indicted Donald Trump, he doesn’t have a prayer of winning his race in November. But like Trump, remaining in the contest lets him use his campaign war chest to pay his own legal bills. (You might think he’d have a gold bar or two squirreled away for a rainy day like this.) Ryan Cooper writes in The Prospect:

The sheer comical excess of the Menendez indictment illustrates how rampant political corruption is in this country. The reason people getting nailed by law enforcement for corruption tend to be people with literal gold bars and stacks of cash sewn into their jackets is because of Supreme Court decisions making it impossible to prosecute instances of corruption that are somewhat more deniable. In McDonnell v. U.S., the Court unanimously overturned the conviction of a former Virginia governor and his wife who had set up meetings with officials for a pharmaceutical company while taking valuable gifts from the company’s owner. In FEC v. Ted Cruz for Senate, it ruled that candidates can loan their campaigns money, and then pay themselves back with donor cash after the election is over and the victor is known—effectively opening a window labeled “bribes here.” And in Citizens United v. FEC, of course, they legalized effectively limitless corporate spending in politics . . .

So while Menendez was doing the kind of idiotic corruption that actually may have run afoul of the remaining shreds of anti-corruption law, now he is taking advantage of a more subtle variety: spending his campaign money on his legal bills. Should he actually contest the Senate election this year, he is absolutely certain to lose—a recent poll found him with 75 percent disapproval among New Jersey residents—and he’s already given up on seeking re-election as a Democrat. But pretending to be running allows him to spend his remaining campaign funds on his legal defense. Just between October and December last year, he spent $2.3 million out of his campaign coffers on legal fees. And as of the end of December, there’s still another $6.2 million in that account. This is all apparently aboveboard.

2. Take It From This Guy

Sometimes a headline is an automatic click. “It used to be my job to drive ships under bridges,” former Royal Navy officer Tom Sharpe writes in The Telegraph this week. “Things do go wrong”:

One thing that the emerging videos and reports of this incident make clear is that on approaching the bridge, the Dali suffered a loss of electrical power, indicated by all the internal and upper-deck lights going out. This is a horrible thing to happen at the best of times. Everything goes dark on the bridge. Radars, radios and any number of little lights, all dimmed to keep your night vision, all simultaneously go out. The constant hiss of the air conditioning which you never notice becomes deafening in its silence. Then the alarms start. Alarm panels on battery backup flash into life and all start beeping to tell you something is wrong. These need to be cancelled so you can hear yourself think.

Then you need to quickly assess what systems you have available. One of the problems with ‘dropping the plant’ is that the resultant equipment failures are never the same. Have you lost propulsion? If ‘no’, do you still have control over it or is it stuck at whatever setting you last ordered? How long before you can switch over to backup systems? Critically, do you have control over the rudder, if not, what angle is that stuck at? While you work this out you must ask are you navigationally safe and if not, how long have you got?

A total electrical failure (TLF) happens when whatever is producing your power trips out. There is always redundancy, especially when operating in confined waters, but the surge in load on those secondary systems can cause them to trip as well. It can also happen when the switchboard, or whatever you have in place to manage that power, itself trips. There are lots of variations within this: the point being, that the order in which it happens determines what systems you lose along the way and in those first few seconds, you don’t know.

As someone who graduated from a maritime college--albeit I'm not STCW/USCG certified as I went the US Navy route sans-USCG/STCW certification (the norm, not an exception), I'll say that I'd be *very* surprised if this was about the USCG coast guard inspection missing something. STCW requirements and inspections are *no forking joke* and the institutes that mint 3rd mates and 3rd engineer officers have extremely stringent requirements and testing standards. The industry and every ship goes through great lengths to pass these checks and they are very very stringent and are comparable to FAA/NTSB standards for the airlines (this is why the AirMax 9 blowout was such a huge deal and Boeing's CEO is stepping down as a result of a single QAQC event). There will be a massive investigation, and the fault will be found eventually. It could come down to the folks who did the recent maintenance on the ship signing off on it, but I don't think it will fall on the USCG. I also don't think this will come down to any kind of "DEI" BS because every single 3rd mate and engineering officer on that ship went through the same rigorous STCW qualifications and certification standards required across the industry. If there is fault with the crew, that fault will not be there because of relaxed STCW standards for "diversity"--there are no sliding standards for qualification/certification between men or women or racial groups in the Maritime industry the way there are for physical fitness standards between men and women in the military and police forces.

From what it sounds like, the crew responded in appropriate fashion to an emergency and so did the police in a very short time frame. If they were able to change the ship's lighting at all (the power went out) they would be flying "red over red, the captain is dead" on their lighting scheme while sending out the emergency call on the appropriate radio frequencies. That the police got the signal and closed the bridge means that those signals went out. The loss of life thus far is tragic but could have been so much worse had this happened during daylight working hours and we're lucky that this happened at the hour that it did. These conspiracy theories out there are absolutely batshit crazy.

While the printing press ushered in religious wars, but ultimately the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution, our current communications revolution is causing pre-Enlightenment mindsets to spread like wildfire. The belief that "everything happens for a reason," or, "there are no coincidences," leads people to preposterous conclusions, where the internet is turning the entire world into Russia, just one big, global zone flooded with shit. Our species is backtracking intellectually while offloading more and more of our cognitive load to machines, and I don't think that ends well.

I am so sick of everything has to be a conspiracy. Sometimes, almost all the time actually, things are exactly what they look like, and no God or secret cabal of Democrats or globalists or terrorists is pulling the strings. People need to get much better at accepting the philosophical wisdom of "Shit Happens." Whatever happened to "Shit Happens?" Did the internet kill it?