Russia Invaded Ukraine. Blame America First.

A new history of the war in Ukraine ignores the main characters.

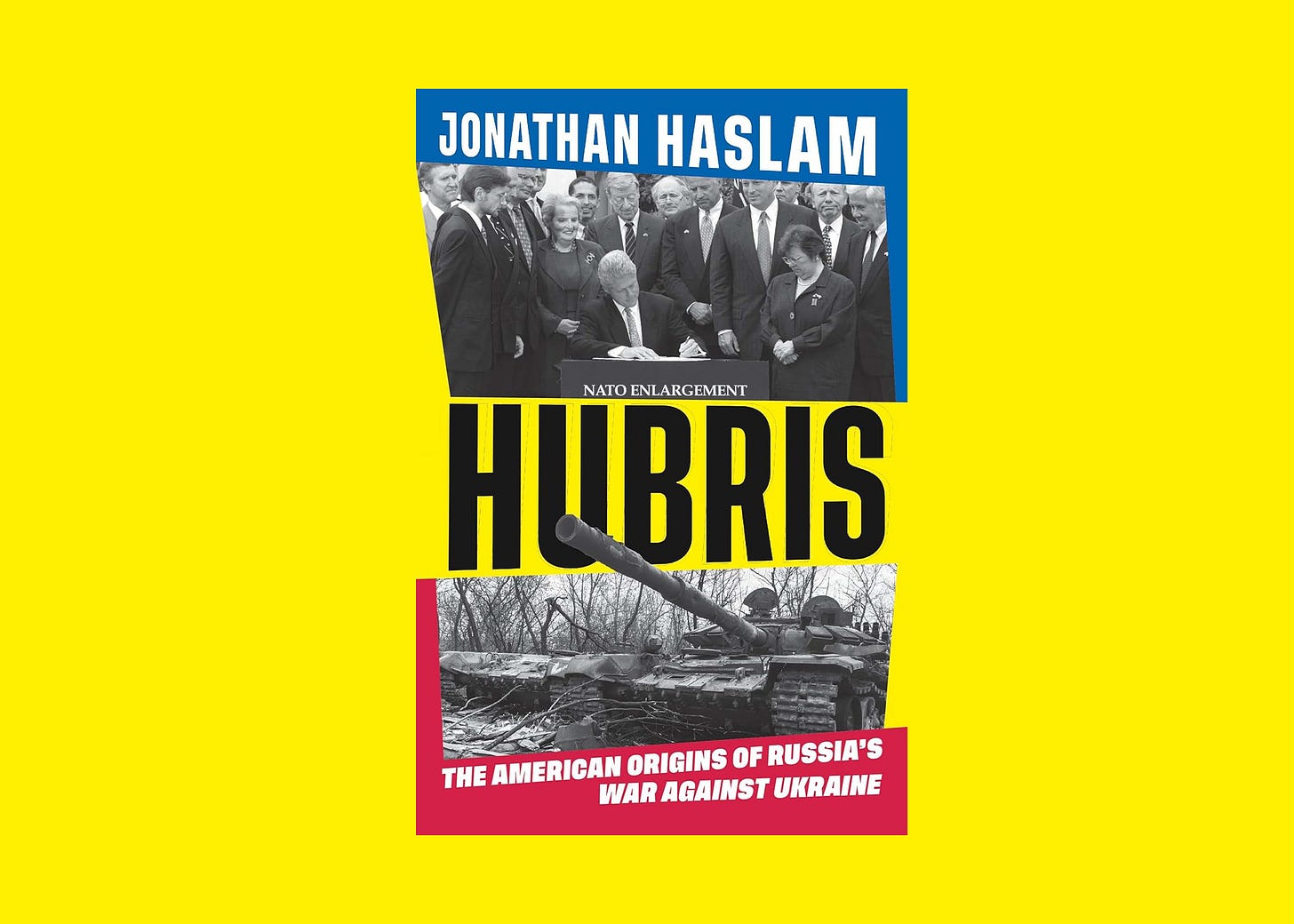

Hubris:

The American Origins of Russia’s War Against Ukraine

by Jonathan Haslam

Harvard, 368 pp., $30

THE WORD “HUBRIS” HAS COME UP frequently since Russia launched its full-scale war against Ukraine. The most straightforward and obvious application is to the architects of the unprovoked, unjust, and so far spectacularly unsuccessful aggression that has failed to subjugate Ukraine at the cost of some 600,000 Russians (and North Koreans and others) killed and wounded and untold injury to the Russian economy. It takes a little more circuity to apply the word to American and European policymakers. By some accounts, it is not the hard men in the Kremlin, but the leaders of the liberal West that are almost exclusively guilty of the arrogance of power.

In the upside-down logic that calls itself anti-imperialist but blames Westerners for Putin’s reconstruction of the Russian Empire, the United States and its allies in the post-Cold War era bear the lion’s share of responsibility for the largest war in Europe since World War II. Instead of showing magnanimity in victory after the collapse of the Soviet Union, according to this view, Washington supposedly provoked Russian ire by extending America’s unipolar dominance under the guise of a Europe “whole, free, and at peace.”

Jonathan Haslam, professor emeritus of the history of international relations at Cambridge, acknowledges the peculiarity of the blame-America-first line in the opening sentences of Hubris: The American Origins of Russia’s War Against Ukraine—and in fairness, it’s also right there in the subtitle. “You might have thought a book about the origins of Putin’s war against Ukraine is all about them,” he writes, emphasis in original. “But, certainly in the first instance, paradoxical though it may appear, it is also about us. And us means the United States and its allies in Western Europe.” Note to any Central or Eastern European readers: You’re secondary to the story.

Even after the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there are still some who maintain that NATO somehow provoked the invasion and that the freely elected government in Kyiv is a creature of the West.

On that last point, many Ukrainians would agree—they want nothing more than to take their rightful place in the West. Curiously, the self-proclaimed anti-imperialists seem consistently to disregard the wishes of Europeans, especially those formerly within the Soviet empire, to live in free, peaceful countries. This is where the narcissism of so much “anti-imperialist” commentary becomes apparent: by emphasizing the American role while paying less attention to—or outright ignoring—the agency of smaller countries like, say, Ukraine.

HUBRIS REHEARSES THE MOST sophisticated version of the argument that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has been widely misunderstood. Far from being a paroxysm of imperial ambition motivated by a foreign policy based on ahistoric ideas of ethnic kinship, Russia’s invasion was, in Haslam’s view, actually a defensive maneuver against an encroaching liberal empire. To support his argument, Haslam has assembled a mountain of evidence in multiple languages. The notes are extensive and the sources varied. Hubris presents probably the strongest “realist” case that American foreign policy made inevitable Russia’s aggression against Ukraine—but it still fails.

Haslam’s main argument is that the war in Ukraine can be traced back to the negotiations between Russia and the West following the collapse of the Soviet Union. This position is defensible, but also reductionist in that it ignores the role that Ukrainian independence itself played in bringing down the Soviet Union, as historians like Serhei Plokhy have documented so deftly. Haslam posits that Russia became resentful of Western triumphalism and over time became incited to belligerence by NATO’s acceptance of new members in Central and Eastern Europe. Haslam may be right that the enlargement of NATO, and subsequently of the EU, stoked fears among the Russian elite about a concerted attempt to marginalize Russia, reduce its role in global affairs, and cut off its influence in Europe. That fact is an indictment of Russia’s rulers, not of its former colonial subjects, its democratic neighbors, or the United States.

Haslam dismisses the conventional arguments from a bevy of American diplomats and scholars that successive U.S. administrations tried in good faith to integrate post-Soviet Russia into the international system, welcoming it into the G7 (subsequently G8, then G7 again), establishing the NATO-Russia council, and accepting that Russia would inherit not only the Soviet Union’s permanent membership of the United National Security Council but also its nuclear arsenal at the expense of other post-Soviet states. He insists that the American response to the Soviet collapse was to pop champagne corks, which helped squander the opportunity for peace at the end of the Cold War.

This is a distortion of the historical record. Haughtiness was hardly the defining theme of the George H. W. Bush administration, whose adroit diplomacy helped ensure that the Cold War ended bloodlessly. “Bush legs”—dark-meat chicken shipped from America to Russia to help feed Russians during the needy 1990s—were hardly a sign of “a triumphalist mood.” The Clinton administration was no more heavy-handed as it sought for Russia to join the Atlantic alliance. Although Russians understandably chafed at Western support for Yeltsin’s corrupt, chaotic, and sometimes violent rule, there were nevertheless vast economic benefits conferred on Russia when it was welcomed into the World Trade Organization.

Along with many other critics of recent U.S. foreign policy, Haslam summons the bogeyman of NATO’s successive enlargement to explain Russian military aggression. But after the Soviet collapse, the formerly “captive nations” of Eastern Europe were eager to escape the orbit of an unfriendly post-imperial state. NATO enlargement was scarcely conjured up by triumphant American statesmen. Rather, it was anxious Europeans who begged for Brussels and Washington to open up NATO membership before Russia regained its old strength and stature, and perhaps nothing motivated them more than the ruthless, atrocious violence of the First Chechen War. Placing the onus of responsibility for the war against Ukraine on the West also ignores that Ukraine was not given a clear path toward NATO membership thanks to persistent Franco-German opposition.

This is not to deny that NATO enlargement antagonized Russia, or that the policy had detractors in the U.S. foreign policy establishment, though Haslam surely exaggerates when he claims that the risk-averse Pentagon was “marginalized, if not shut out entirely from the crucial decisions.” One of the most prominent naysayers was George Kennan, the architect of containment, who warned about the dire consequences. In 1997, the Sovietologist predicted that “expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era.” Kennan argued that NATO’s drive to the east would simultaneously inflame “nationalistic tendencies” in Russian opinion, corrode the “development of Russian democracy,” and restore “the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations.”

It’s worth remembering, however, that Kennan had also been opposed to the founding of NATO in the first place. He withheld his support for this linchpin of collective security because he was opposed to America’s commitment to postwar Europe and thought a formal military alliance would provoke the Soviets. To the ridicule of military experts at the time, he believed that a small cadre of special forces would be sufficient to deter 300 divisions of the Red Army from plowing through West Germany. After penning the renowned Long Telegram, Kennan’s chronic dissent from American policy was animated by a marked timidity, which led Dean Acheson to describe him as “a horse who would come up to a fence and not take it.”

The bulk of Haslam’s case rests on the betrayal of the apparent promise given to the Soviets that NATO would not expand to the east. He invokes the former French Foreign Minister Roland Dumas, who observed during the days of German reunification that “the West had promised that NATO would not extend to Russia’s doorstep.” This is a tendentious reading of history—which incidentally also undercuts the claim that the West trumpeted its victory in the Cold War. But in fact, no such promise was ever given. Haslam makes much ado about the “assurance” supplied by James Baker to Mikhail Gorbachev on this score, but this was no more than a diplomatic thought experiment—hardly a sacrosanct agreement. Tellingly, on the subject of the Budapest Memorandum, Haslam is far more lenient about broken “promises.” He treats Russia’s pledge to respect Ukrainian sovereignty in exchange for Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament as not being worth the paper it’s written on since it was not ratified by the Duma.

Hubris adds nothing new to the debate over putative promises not to accept new members into NATO. In fact, Haslam appears not to be caught up with the field. He does not cite Mary Sarotte’s Not One Inch, which has become the definitive history of the issue since its publication three years ago. Sergei Radchenko, in his monumental history To Run the World, published last year, provides a slightly different take on the “not one inch” debate—but Haslam doesn’t cite him either.

Instead of relying on the most up-to-date research, Hubris rests on dubious assumptions and assertions. For instance, a central conceit of the book is that Europeans have been in lockstep with the Americans regarding Russia (and many other geopolitical matters) since the end of the Cold War. To believe this, one either has to be deep in the orbit of Kremlin propaganda or a consecrated Little Englander with a visceral distaste for American global leadership. It’s hard to think of a period since the end of the Cold War in which there was no tension in the trans-Atlantic relationship, but Emmanuel Macron’s 2019 declaration of the “brain death of NATO” stands out as an example Haslam should have remembered.

For three decades after the end of the Cold War, the relationship between Russia and Europe was remarkably close, even cordial—especially with Germany, which adhered to Bismarck’s advice to “never cut the tie to St. Petersburg.” In the euphoria that followed the breakup of the Soviet empire, many on both sides of the Atlantic expected that Russia would become a liberal democracy and a stakeholder in the global order. Even if there was a marked Western indifference to the wrenching difficulties of a society in transition, there was also widespread economic and political support for an enhanced partnership with Russia. This was partly due to Europe’s dependency on Russian oil and gas, but the larger factor was a naïve but sincere presumption about the universality of liberal ideals that would ease if not erase tensions between old adversaries.

Even after Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, when Americans gradually—one might say belatedly—became more skeptical of Russian motives and intentions, the prevailing imperative in Washington, to say nothing of the capitals of Europe, remained keeping good relations with Moscow. At no point did Western leaders treat the Russian autocrat as anything but a “partner in peace”—on Russia’s periphery and even in the Middle East, where Obama thought a working relationship with Putin could help stabilize the region.

This genteel approach did nothing to dampen Putin’s expansive ambitions. First, he subdued Georgia in 2008. Then he corralled Belarus as a satellite regime. He seized Crimea and incited conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014. The West greeted all these depredations with a collective shrug, implementing soft sanctions against the Russian regime and declining to arm Ukraine with serious armaments to deter further aggression. This policy of accommodation lasted until the last moment, as Russian armies crashed into Ukraine in 2022. The Nordstream pipeline project between Russia and Europe was a casualty of this war, as was America’s reluctance to supply and arm Ukraine in its battle for survival.

BEYOND THE DIVERGENCE OF GEOPOLITICAL interests, there is a deeper philosophical matter at issue. Haslam rightly argues that Russia has never been a “normal” state, but rather a longstanding imperial power. (The word “tsar,” he reminds us, means Caesar.) He notes that in 1992, “the Russian people were utterly baffled at the lightning speed with which their apparently mighty country . . . completely disintegrated around them.” This psychological trauma imparted a fertile environment for nostalgia. “Losing an entire empire at one fell swoop,” he elaborates, “is a devastating blow to the self-esteem of any proud metropolis.” He’s not wrong, but he also fails to acknowledge the degree to which it was not Americans or Britons or Germans but Soviets who eventually brought down the Soviet empire.

It’s undoubtedly a difficult thing to lose an empire and to be relegated to the second tier of world powers, but it’s hardly unprecedented in the annals of history, as Haslam knows well. He juxtaposes the historic defeat of the Soviet Union and the commensurate loss of imperial grandeur with the experience of former empires that broke apart—the Spanish, the Portuguese, and the Dutch. But he does so without assimilating the fact that these ex-imperial powers made their peace with the modern world and found ways beyond martial conquest to slake their wounded national pride. Russia is a great country that should always be treated with appropriate respect. But in no way does this entitle it to reestablish an empire by force—to build what Putin calls Russia’s “great Eurasian future.”

And yet that’s precisely what Haslam seems to believe. He invokes Boris Yeltsin’s “strange” final meeting with Clinton, at which the outgoing Russian president begged his American counterpart to focus his nation’s attention and ambition on the wider world. “Just give Europe to Russia,” he pleaded. In the world of diplomacy, this is not the sort of tone that warrants extraordinary deference. It deserves to be met with an unequivocal insistence that there is a line beyond which unscrupulous conduct in foreign policy would be incompatible with good relations.

There’s no sign that Haslam grasps the manifold dangers posed by the threat of Russian revanchism. Clinton, for his part, recognized these dangers when he replied to Yeltsin, “I don’t think the Europeans would like this very much.” The disgrace of American and Western statecraft in the post–Cold War era is that this sound instinct was not combined with strong deeds.

In the closing pages of the book, Haslam concedes the point more succinctly than his critics ever could. He writes of Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, “The bottom line was that in keeping his own counsel he simply blundered.” Sounds like hubris.