Why Trump’s Attack on Refugees Could Hurt Grandma

It’s immigrants from ‘shithole’ countries who care of our elderly, and nobody’s lining up to take their place.

Miami, Florida

MARYSE, 56, HAS BEEN A HOME CARE WORKER in the United States ever since she moved here from Haiti sixteen years ago. Over the years, she estimates, she’s cared for more than two dozen people. Most have been seniors in physical or cognitive decline—among them, a Purple Heart recipient who had served in the Army and a former pilot who had flown missions over France and Africa during World War II. She has also cared for younger people with physical disabilities, including one who had cerebral palsy and another who had suffered severe head trauma in a car accident.1

It was not the career Maryse once imagined for herself, she told me last week. Back in Haiti, she was a journalist. But that was before a 2010 earthquake killed an estimated quarter million people and destroyed more than half of Haiti’s infrastructure, plunging the island nation into a state of extreme deprivation and violent anarchy.

At the time of the quake, Maryse was staying with family in the United States, her two children in tow, wondering what kind of life waited for them back home—or if they could even survive there at all. That’s when the Obama administration granted Haitians “temporary protected status” (TPS), a designation that allows foreigners to stay and work in the United States legally when their home country has become dangerous because of natural disaster, armed violence, or other “extraordinary” circumstances.

Maryse’s priority at that point was providing for her kids, and her English wasn’t good enough for media work in the states. At her sister’s urging, she says, she enrolled in classes to become a certified nursing assistant, following a well-worn path for Haitian immigrants who knew the high demand for caregivers meant it would lead to reliable employment—and who frequently saw caring for others as a calling, not just a paycheck.

The work has never been easy or simple. A typical day will involve some combination of cooking and driving, bathing clients (home care workers typically don’t refer to them as “patients”) and helping them with the toilet. Sometimes the most important thing is to provide simple companionship, she told me, whether it’s on a walk in the park to hear old stories or in front of the television to watch Wheel of Fortune.

The job is almost never just eight hours a day. The challenges include dealing with the physical strain of lifting adult human bodies. But Maryse says she doesn’t have a problem with what you might imagine as the jobs’ more difficult aspects, like the ickier parts of bathroom duty or the emotional drain of getting to know people just as they are in the twilight of their lives. “I really like helping these people and it reminds me how vulnerable we all are,” she said. “I do it with as much heart as I can.”

But these days Maryse has been preoccupied with another subject: Donald Trump’s anti-immigration agenda, and what it would mean for people like her.

An order that Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem issued in November revoked TPS for the roughly 330,000 Haitians who have it. And while a federal judge blocked that order right before it was to take effect last Tuesday, the Trump administration says it plans to appeal. At least for the moment, the administration is also ignoring pleas from a coalition of pro-immigration advocacy groups and high-profile Democrats—along with the occasional swing-district or -state Republican—to relent.

Trump’s determination to get these Haitians out of the country is a subset of his larger project to rid the United States of refugees from what he calls “shithole countries.” The way he and the MAGA faithful tell it, the Haitians are a burden on American society and a threat to its culture—a “filthy, dirty, disgusting” group of people so depraved that, as he infamously said during the 2024 campaign, they were eating their neighbors’ dogs and cats.

But just as the pet-eating story was apocryphal, Trump’s portrayal of the Haitian community’s role in society is way off—especially in places like South Florida, where so many Haitians are providing support for some of the most desperately needy people in society. If the refugees lose their right to stay they won’t be the only ones to suffer.

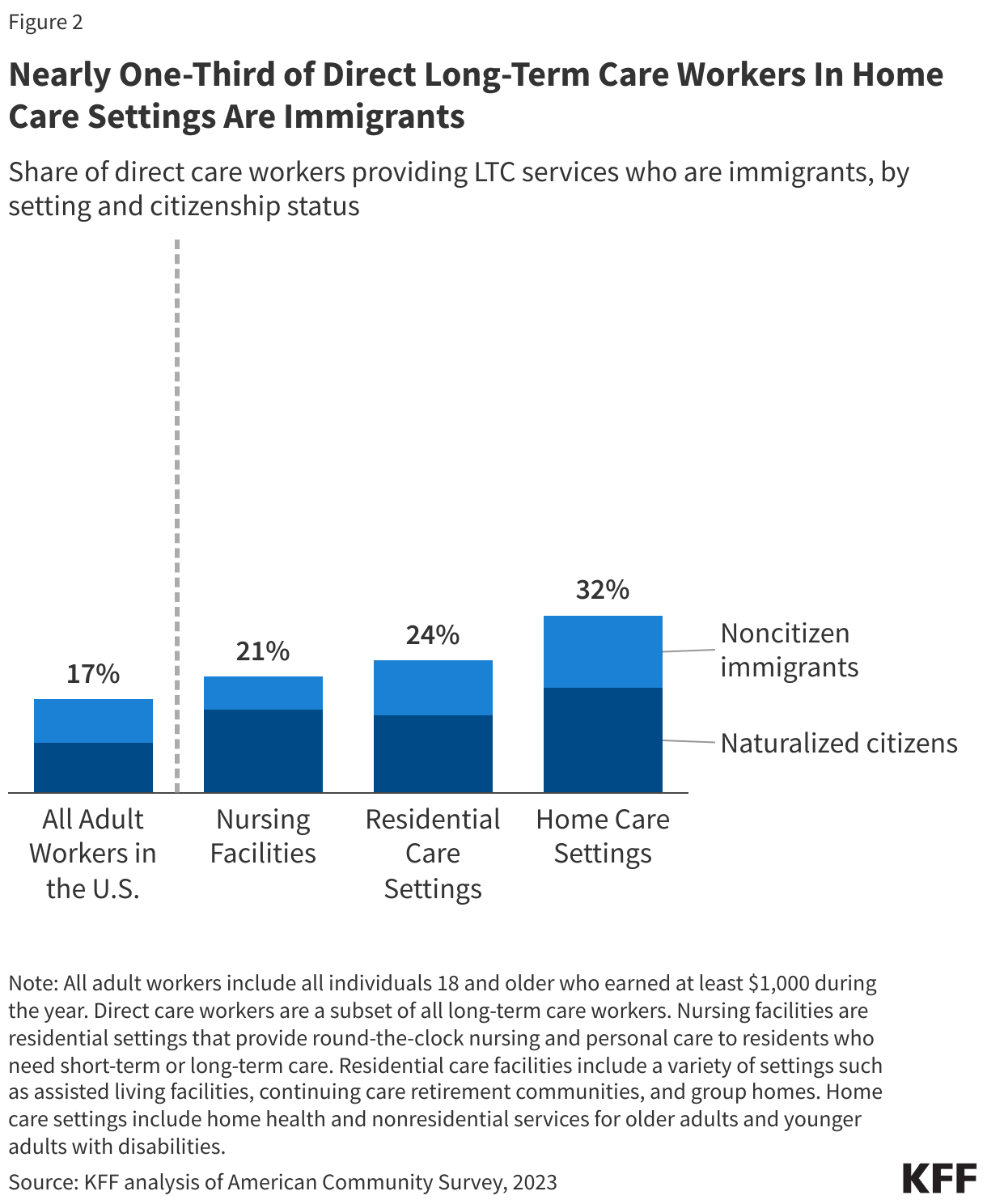

IT IS DIFFICULT TO IMAGINE what care for seniors and people with disabilities would even look like without a large immigrant component. While foreign-born citizens and noncitizens account for just 17 percent of the adult workforce, they make up 28 percent of the total direct care workforce, according to analyses by the policy research organizations KFF and PHI.2

This is not a case of immigrants taking jobs from Americans, most economists say. It’s a case of immigrants taking jobs Americans don’t want, because there are easier ways to make a living. “There are these other jobs—even fast food sometimes—where you can have more predictability and stable hours, and make similar money,” Robert Espinoza, a distinguished fellow at the National Academy of Social Insurance, told me.

That’s a good argument for raising pay and improving conditions for care workers, as labor unions and other advocates for workers have long argued. But doing so would require the kind of legislation and financial commitment not likely to come from a president and a Congress who spent the last year hacking away at Medicaid, the nation’s largest financier of long-term care. And even if a substantial new investment in caregiving were in the offing, it’d be unlikely to meet the needs that exist already, let alone in the future given America’s steadily aging population.

This kind of in-depth reporting and analysis—so important to the future of our democracy—is made possible by the support of our Bulwark+ members. If you’re not already a member, consider joining today at 20 percent off the regular price.

“There are literally millions of people who rely on immigrants for their basic care needs every single day,” Ai-jen Poo, president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, told me. “With the growth and demand for care work, particularly in the home and community where most people want to age . . . I don’t see how we meet anywhere near the demand without a really strong presence of immigrant care workers.”

She’s not the only one who thinks so. A 2025 analysis from the (left-leaning, pro-labor) Economic Policy Institute found that if Trump succeeds in his goal of deporting 4 million people in four years, the number of direct care workers would shrink by 400,000.3 And while those sorts of projections are hardly an exact science, they are consistent with warnings from leaders of Florida’s care industry, where one group of immigrants—Haitians—constitutes a crucial part of the workforce now at risk because of Trump’s threat to revoke TPS.

“I wouldn’t say that a lot of [facilities] are going to close their doors, but from the providers that we’re seeing and hearing, it’s definitely going to raise prices and it’s definitely going to increase the waiting lists, which is a bigger issue,” Luis Zaldivar, project director at the American Business Immigration Coalition, told me. “Nursing homes have very long waiting lists to get in—and with this, they are just going to get longer.”

Zaldivar cited as an example some recent statements from the director of a Palm Beach County nursing home. In interviews with the New York Times and Miami Herald, the director said many of her Jewish residents were distraught at the prospect of losing their Haitian caregivers—and asked if they could hide them, as some gentiles had done for Jews during the Holocaust. “There are many others who would like to speak up, but are afraid of retaliation,” Zaldivar said.

Two weeks ago, Zaldivar stood at a press conference alongside Thomas Wenski, who as Miami’s archbishop has a formal supervisory role for Catholic Health Services—a major supplier of home care services for South Florida. Wenski told me during an interview last week he’s seen firsthand the indispensable role Haitian workers play—not just by filling employment slots, but by providing the kind of care the most vulnerable people need.

“If you have your grandmother or your mother in one of these nursing homes, and the care that is being given to them is by a Haitian worker, you come to appreciate their contribution,” Wenski said. “They come from a very traditional society in which grandparents and elders are very much respected. The extended family is very much alive in Haiti, and the values of that are reflected in their work.”

I heard the same thing from others—including Tessa Petit, who came to the United States from Haiti in 2001 and now leads the Florida Immigrant Coalition. She told me about a Haitian proverb, Bourik fè pitit pou do l poze, that translates roughly as “the donkey has little ones to rest her back” and that conveys the expectation children will care for their elders.

“Everywhere around the country, people will tell you that Haitian workers are very empathetic, they’re supportive,” Petit said. “No job is too belittling when it comes to taking care of sick people, and taking care of their elders. Why? Because it comes from a culture where our older folks stay home and care for them. It’s normal to care for your loved ones.”4

THE FEDERAL JUDGE WHO BLOCKED Noem’s order last week determined that the secretary acted, “at least in part,” out of “racial animus,” and failed to conduct the kind of careful analysis necessary to make an informed decision about whether Haiti’s conditions had improved enough to make return safe. But while the judge had sound reasons to reach all of these conclusions, there’s no guarantee her ruling will hold up on appeal..

That is why advocates keep talking about the decision not as a victory but as a reprieve, and are focusing on rallying political support. That includes pressuring lawmakers to support a discharge petition in the House, filed by Massachusetts Democrat Ayanna Pressley, that would force House leadership to bring to the floor legislation extending TPS for Haitians.

As of Saturday evening, the signers included 127 Democrats and a lone Republican, Maria Elvira Salazar, whose Miami-area district (like Pressley’s) has a significant number of Haitian voters. But organizers told me they were hopeful of rallying the rest of the Democratic caucus—or at least most of it—and then flipping a handful of Republicans in vulnerable districts that also have large numbers of Haitian immigrants. (One likely candidate is Mike Lawler, the New York Republican who has already indicated his support for maintaining TPS.)

A bill passing the House would still need to get through the Senate, and then get Trump’s signature. That’s hard to fathom. The only shot might be attaching a TPS extension to must-pass legislation—and then convincing Trump (or people around him) that his crusade against Haitian refugees isn’t worth the political costs of alienating voters in states like Florida, New York, and Ohio where the local impact of ending TPS could be enough to swing votes in contested congressional races.

That kind of hard-nosed calculation is necessary because Trump has made so abundantly clear his desire to expel immigrants who hail from countries like Haiti. But he and his party still depend on the political support of people who may not have thought through what a crusade of mass deportation would really mean in practice—or how it might affect themselves or their loved ones if they someday need care.

“We do the job that nobody wants to do, with low pay, and we are proud of doing that,” Margarette Nerette, a vice president in the Florida chapter of 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, told me. “We become their mother, their grandmother, their sister, their brother. We feed them, we clean them, we put them in the chair, we put them in bed. That’s awesome. When they are happy, we know it. When they’re not happy, we know it too. Because we are there for them.”

Maryse asked that we use only her first name for this article.

The “direct care workforce” includes employees of nursing homes and assisted living facilities, as well as workers who care for people in their homes.

Not all of the vanishing workers EPI projects would be immigrants leaving the country or dropping out of the formal workforce. About 120,000 would be U.S. workers—in part, because of the way labor shortages in the care industry would ripple through the economy.

Haitians aren’t the only immigrant group with a reputation for a strong caring ethos. Filipinos have also had that reputation, enough that there’s a well-known pipeline for nursing from the Philippines.

Ai-jen Poo, who has also written a book called The Age of Dignity, told me that “Different cultures around the world treat aging and caregiving differently, and some cultures really uphold and uplift older populations. . . . That is a cultural norm that we do not have in our country. But coming from that cultural norm into ours, I think it really delivers people right into a sense of calling.”

Having kind, committed, yes loving caregivers for our elders is a godsend. The caregivers in my mother’s assisted living facility were essential to my brother and me as we cared for our mother in her last years. My brother and/or I were with my mom everyday at all hours of the day. The nurse’s aides were there when we couldn’t be. Thank God for their consistent care and compassion. It is stupid and shortsighted to deport people because of their skin color. Such actions deprive our society of people making valuable contributions. People like the orange menace, Stephen Miller, and Kristi Noem are working to turn the US into a shithole country.

Haitian immigrants are amazing, hard working, decent people. I grew up in south Florida and I’ve known many. We will all be worse off if they’re forced out.