Wary Dems Weigh Working With Trump Team

They know there’s always a risk they’ll be burned.

A HOST OF PROMINENT POLITICAL LEADERS descended on Onondaga County, New York, last week to mark the official groundbreaking of a $100 billion semiconductor manufacturing facility by Micron Technology.

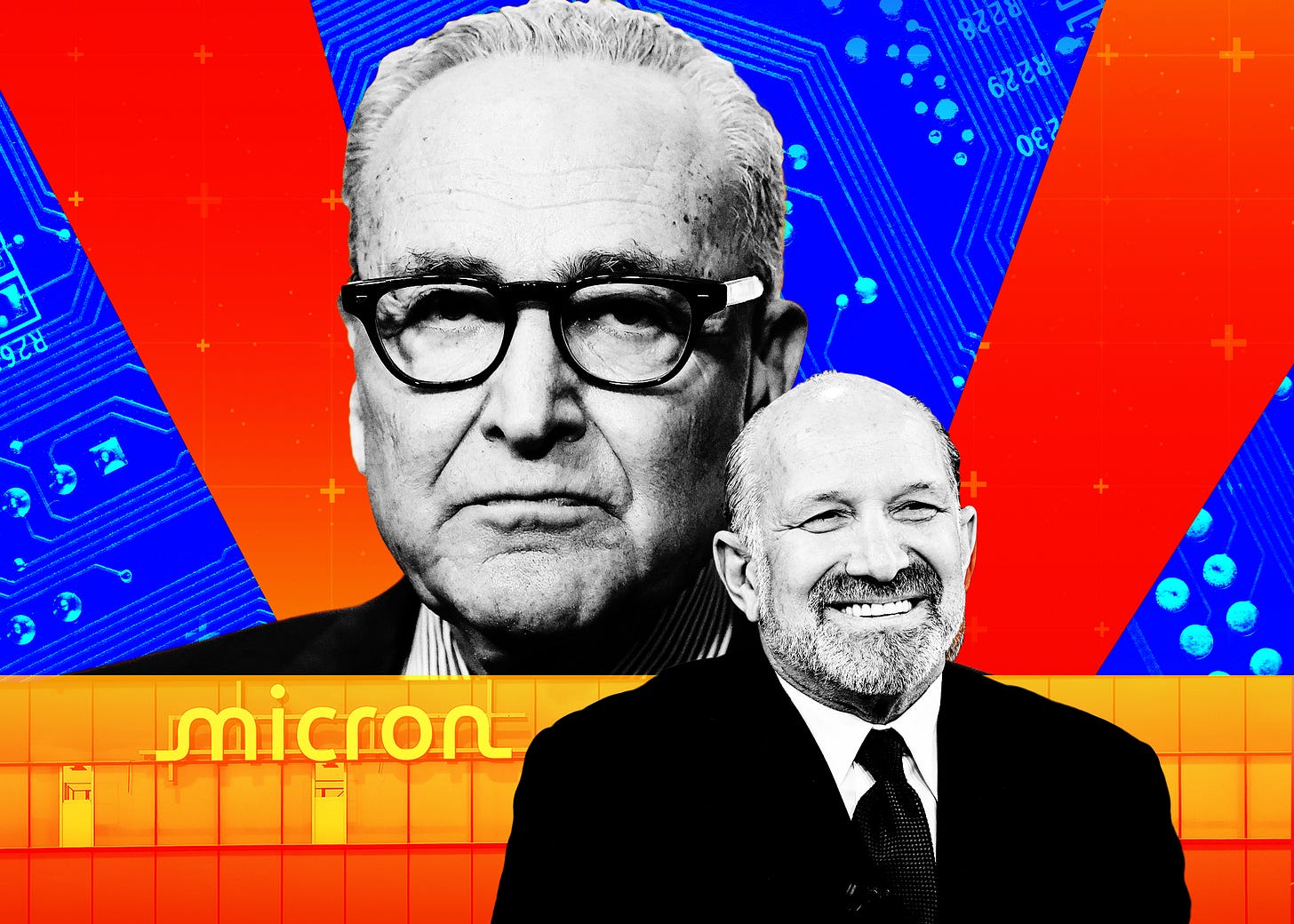

Among those in attendance were Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (New York’s senior senator) and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick.

It was by all accounts a celebratory affair—befitting the launch of a venture expected to bring around 50,000 jobs to the central New York region. But it was a political event, too. Micron’s expansion was initially made possible by the CHIPS Act, which President Joe Biden signed into law, and which Donald Trump opposed. And so, as the gathered politicians and Micron CEO Sanjay Mehrotra took questions from the press, Luke Radel, a college reporter from nearby Syracuse, posed a question to Lutnick: Why should Trump get credit for these jobs?

Lutnick geared up to answer. But before a word left his lips, Schumer—a Buffalo Bills beanie tented over his head—jumped in: “We’re not looking for one side or the other,” he said. “We’re working together to make this thing happen in the right way.”

Such a plea for comity may have been reciprocated in normal times. But these aren’t normal times. Later that day, the Commerce Department posted a glossed-up promotional video about the Micron groundbreaking. Schumer was not even in it. Instead, it featured Lutnick mugging triumphantly in a variety of settings: shoveling dirt, striding alongside Mehrotra, photographed with his arms crossed and a vainglorious grin, boasting from a lectern that Biden had secured a measly $75 billion investment from Micron while Trump had negotiated one for $200 billion.

Lutnick’s crowing was a vivid reminder that there is no such thing as sharing when it comes to spotlights and Trump. But it also reignited a question for Democrats: Just how closely, if at all, should they collaborate with this administration, especially in an election year?

It’s a question faced by every party in the minority. Handing a president a bipartisan win is not something casually done when ballots are about to be cast. But it’s a particularly tricky proposition now—not just because it seems downright anathema to work with Trump while he tramples norms, rights, and the rule of law in a host of different areas, but also because Trump has suddenly begun embracing the policy hobbyhorses of some on the left.

In recent weeks, Trump has advocated capping credit card interest rates at 10 percent, announced the purchase of $200 billion in mortgage bonds in an attempt to lower the cost of home loans, and said he would back legislation that would prevent private equity firms from buying up single-family homes. A number of progressive Democrats would love to see these proposals signed into law. And in conversations throughout the past week, party officials confessed to feeling a bit torn. In their hearts, many fancy themselves as wonky do-gooders fundamentally uncomfortable with putting politics ahead of apparent legislative progress.

But none of them are thrilled about the idea of working with the administration. Nor do they want to give the president any cover in a year when so much will hinge on his ability to lower costs.

“We won’t close the door on something. The question is whether it is meaningful,” is how one congressional aide put it to us. “The political risk is not nonexistent but I don’t think it is the biggest factor.”

Few Democrats are feeling that tension quite like Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren. In a speech last week, Warren went after Trump for “doing not one damn thing” to lower housing costs. After Trump got word of her speech, he called Warren to talk about housing legislation and the cap on credit card rates. In an interview with CNBC afterwards, Warren said: “My job is to do anything I can to lower costs for American families, and the Democratic party is ready to go. We stand behind that. . . . Talk is cheap, but if he’s really ready to put up and get something done, then let’s do it.”

Warren’s office did not say whether she and Trump—or her aides and White House aides—have followed up on those initial conversations. But the sentiment that the senator expressed was echoed by other Democratic officials we talked to. They argued that voters still expected the party to work with the Trump administration and engage with the White House on affordability issues. They’re not sanguine about the prospects or blind to the risks. Few, if any, expect Trump will spend any political capital to pass such legislation. Virtually all believe he was looking for credit, not achievement.

“Anyone who has an opportunity to have a conversation with anyone in influence to make people’s lives more affordable, to address the real issues that people are dealing with—they should take advantage of that,” said Joel Payne, chief communications officer of MoveOn. “But you should not allow your willingness to engage to be used as a political cudgel. Engage in good faith, but also be mindful that there’s nothing about Donald Trump’s agenda that suggests that there is genuine concern to make people’s lives better.”

Even if Trump were sincere—even if, somehow, affordability-focused legislation were to be enacted—it wouldn’t necessarily boost him before the midterms. Bills take time to implement, and credit doesn’t just go to the person who signs the final text.

“If it does happen, it would be objectively good for the country, and frankly, Democrats would get a lot of the credit,” said Douglas Farrar, a former senior adviser at the Federal Trade Commission under the Biden administration. “It’s their bills, it’s their ideas. And if Trump tries and fails, it only further cleaves the president from the Republican party.”

ON THAT LAST FRONT, Farrar is undoubtedly right. Fissures are showing on the right. A number of Republicans have said they disagree with Trump on the credit card caps, and both Senate Majority Leader John Thune and House Speaker Mike Johnson told reporters last week that they were skeptical of the idea. At the same time, GOP Sen. Roger Marshall of Kansas announced plans to introduce legislation that would cap credit card interest rates at 10 percent.

A savvy Democratic party could, in theory, use Trump’s dalliance with lefty policies to try and drive wedges between him and his base. More moderate Dems could even take a chance by trying to burnish their bipartisan credentials. But, in the end, history tells us that the likely outcome is inaction at best and humiliation at worst. Trump’s not interested in policy wins. He’s interested in headlines—and in ritualistically humiliating his foes.

Schumer should certainly understand that by now. One day before the senator stood beside Lutnick, he met with Trump at the White House to discuss funding for the Gateway Tunnel, the crucial Hudson River project in the country’s most important economic hub. The White House had called the meeting, giving the impression that the president was reconsidering his decision to pull the funds during the last government shutdown. Five days later, members of Congress released a major funding bill that would help avert a coming government shutdown at the end of this month.

Gateway Tunnel funding was not in it. According to Burgess Everett of Semafor, the Trump administration intervened at the last minute to ensure it wasn’t included.

My open tabs:

— A Vermont Town Was a Foodie Mecca for Canadians. Until Trump’s Threats.

Schumer is like the woman who goes on a date with the serial killer who has been paroled: "But he won't kill me! He's done with all that."

A risk they'll be burned? More like a certainty.