Welcome to the Heat Death of Neoconservatism

Democracy promotion is dead. Domination Theory is here.

We’re going to talk about Venezuela today, but we have to take a long way round. And you’re not going to like the journey.

One of our recurring themes is how views change over time. I’ve written a fair amount about this, especially how I’ve come to believe in the centrality of race in American politics. Another place where I’ve slightly changed my views is that I’ve become more of a believer in neoconservative foreign policy, the importance of American global leadership, and the ability of the United States to promote democracy.

And I’ve done this while a broad, bipartisan consensus has emerged which holds that the neocons were wrong about everything. 🤷♂️

At this point, neoconservatism is a dead letter. The Democratic party rebelled against it during the Bush years. The Republican party has rejected it under Trump. There is no constituency for neoconservatism anywhere outside of a couple of think tanks in D.C.

But while neoconservatism was in remission a decade ago, its immediate cause of death is the second Trump administration. Let’s dig in.

1. This Ain’t No John Trumbull

Neoconservatism was good, actually.

I’d like to show my work on this. So let’s start by defining “neoconservatism” as the foreign policy impulse which believed that America’s interests were furthered by the expansion of democracy abroad.1

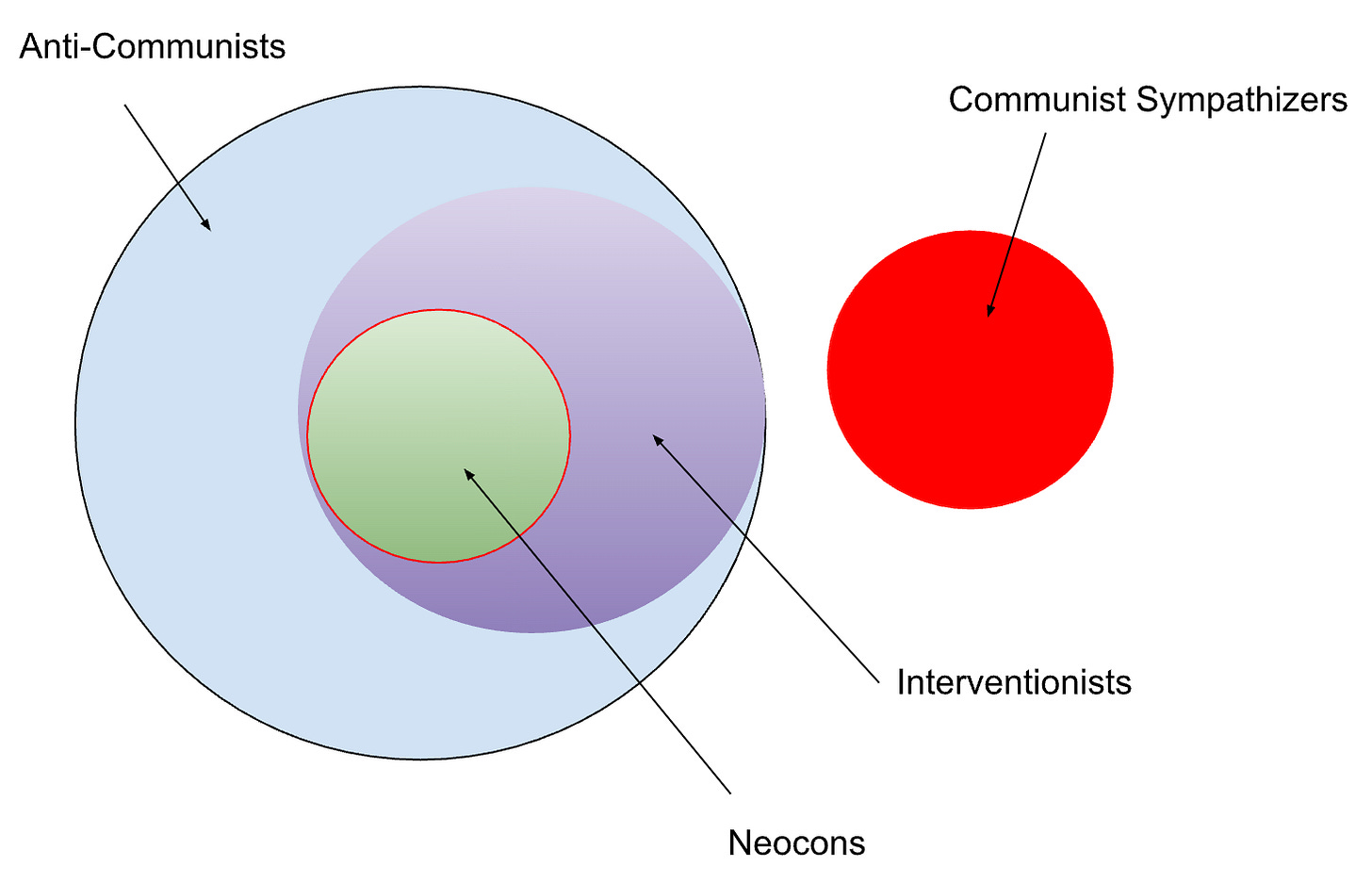

This worldview was a subset of the anti-communist consensus2 which won the Cold War. If you drew up a Venn diagram of the various American foreign policy views following WWII, it might look something like this:

This isn’t a perfect illustration. Somewhere in that blue area are anti-communist isolationists and somewhere in the purple are paleocon interventionists—the kind of people who used to puff out their chests and say “rubble don’t make trouble.”

Also: These groups emerged sequentially. The anti-communist consensus congealed pretty quickly after WWII, but Korea and Vietnam created (1) anti-communists who were wary of intervention and (2) neoconservatives who believed that intervention should be married to democracy promotion and not just about domino theory.

Neoconservatism was messy and often contradictory. It supported democratic movements in some places, but was friendly to anti-Soviet strongmen in others. And once the Soviet Union collapsed, neoconservatism became more expansive, concerned not just with anti-communism, but with repressive regimes of many flavors.

But even once you take all of this into account, I propose that, net-net, neoconservatism was a force for good.

Now let me explain how Donald Trump killed it dead.