Why China's Censorship of Western Art Matters

Plus: 'Tesla' reviewed and 'The Prestige' revisited.

Remember the Tank Man

We were reminded yet again this week of Chinese power over the global entertainment industry’s levers of business when Activision Blizzard was forced to recut a trailer for the new iteration of Call of Duty because the game’s trailer showed a brief snippet of footage of the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

American audiences are so accustomed to the Tank Man—that unknown figure who stood alone, in front of a tank, impeding its progress after the massacre—serving as a symbol of freedom that it likely does not even occur to think that there are people in China who don’t know about him. Literally: have never seen his image.

This is one of the tidbits gleaned from Chris Fenton’s new book Feeding the Dragon: Inside the Trillion Dollar Dilemma Facing Hollywood, the NBA, and American Business. “There isn’t a Chinese citizen who has lived their whole life in China, born around or after June 4, 1989, who has seen the famous photo of the Chinese man staring down a PLA tank in the heart of Beijing,” Fenton writes. “One doesn’t have to live in China to test this theory either. Any freshman at a college in the States can walk up to one of their mainland Chinese classmates, show them the picture, and ask, ‘Have you seen this before?’ As shocking as it seems, I promise the answer will be, ‘No.’”

The clash of technology and history—the effort to control what a video game company can broadcast over the Internet—is especially poignant in this instance, given that the Chinese government’s intense censorship of the Internet has been, at least in part, designed to memory-hole the massacre, as David Gilbert noted last year in Vice.

“The Chinese military killed as many as 10,000 people during Beijing’s vicious crackdown on pro-democracy protesters 30 years ago. But today, those victims and the horrific events of June 4, 1989, in Tiananmen Square have been virtually wiped from China’s collective memory,” Gilbert wrote. “Beijing has achieved this mass erasure through an unprecedented crackdown on all forms of public speech in the streets and online, relying on advanced technology to automate much of their efforts while detaining people like [filmmaker Deng Chuanbin] for making the smallest reference.”

Despite the Great Firewall of China, Gamers have been among the strongest advocates for reform in the Middle Kingdom, using international platforms to push for messages of freedom and democracy. But this erasure of Tank Man isn’t the first time Activision Blizzard has bowed to pressure from the Chi-Coms. Last year, in the midst of the Hong Kong protests, a prominent gamer who uses the handle “Blitzchung” yelled “Liberate Hong Kong” in Mandarin on a Taiwanese broadcast while wearing a gas mask and goggles—a shout-out to those who were being assaulted by the Chinese cops in Hong Kong.

“It was a costly bit of protest,” the Los Angeles Times’s Suhauna Hussain reported. “Blitzchung, whose real name is Ng Wai Chung, was supposed to collect $10,000 in award money for his participation in the Hearthstone Grandmasters competition. Instead, Blizzard Entertainment, the unit of Santa Monica-based gaming giant Activision Blizzard that runs the global competition, kicked him out of the tournament, revoked his prize winnings and banned him from Hearthstone esports for a year, all for expressing support for the pro-democracy protests currently roiling Hong Kong.”

This effort at censorship was so egregious that it sparked a rare moment of bipartisan unity: Republicans Marco Rubio and Mike Gallagher joined Democrats Ron Wyden, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Tom Malinowski in a letter condemning the video game company’s cowardice.

But there are undeniable benefits to playing ball with China. And it’s not just access to markets. As Fenton notes, when it’s clear the Chinese government wants to play ball with someone—and that someone is willing to play ball in return—there are all sorts of ancillary benefits, such as more rigorous protection of intellectual property.

“The black-market Marvel store in Beijing’s U-Town mall mysteriously vanished,” he writes of Chinese marketplaces following the deal to make Iron Man 3 a Chinese coproduction, “and my favorite black-market DVD store in the Sanlitun alley, behind Beijing’s Opposite House Hotel, had stopped selling Marvel titles too.”

I’ve been banging away at this drum for weeks now, in print and on podcasts, but it’s a key to understanding the modern entertainment industry: China’s influence is supreme and only likely to grow as domestic and European box office figures are slow to return to normal. And we ignore their aggressive intrusions into our arts at our peril.

Review: Tesla (VOD)

The cult of Nikola Tesla is one that has fascinated me, kind of, for some time—ever since I was a kid and my house would receive these little mini-catalogs with all sorts of weird, sub-Brookstone stuff. Maybe these are long-lost remnants of my childhood—it’s hard to imagine them existing in the internet age—but they’re the kind of catalogs that chaps by the name of Santos L. Halper would order a dog out of, just jam-packed with weird crap designed to inspire splurging by those with low impulse control and an unduly high credit limit.

Jammed somewhere in these catalogs among the vibrating foot pools and the digeridoos, there was always a section on . . . Tesla. Cheap, flashy Tesla coils would give way to biographies of the great unsung hero of the electrical revolution and books promising the secrets to free, unlimited power. You know, the sort of thing you find alongside 1,000-count bottles of caffeine pills and miniature slot machines.

Tesla holds an oddly sainted place among both artistic and tech types: a loner and a genius who went up against Thomas Edison and found himself unappreciated, relegated to the dustbin of history, unable to navigate the world of PR and wealth that is required of a businessman. He earned a brief appearance in Tomorrowland and a longer one in The Prestige, both notable for their conflation of science and magic. (More on The Prestige in assigned viewing.) Last year saw the release of The Current War, which posited that Tesla’s preferred alternating current was unfairly sabotaged by Edison in his quest to have direct current adopted as the standard. Tesla, of course, won out: It’s alternating current that powers your home, after all.

Or did he? Tesla died alone and impoverished, his name far less well known that Edison’s; as we learn in Tesla, if you Google them both you get roughly twice as many hits for Edison as you do for Tesla. Tesla is full of little asides like this, little intrusions of our present into the distant mist of the past, a continuous suggestion by writer/director Michael Almereyda that we truly live in the world that Tesla created.

It is certainly an unusual biopic, this Tesla, one that combines the trappings of the genre—period clothing and period set dressing and period people speaking period patois—with a playful refusal to abide by the rules of the genre. Or any genre, really.

We follow Tesla, immigrant extraordinaire, as he gets out from under Edison’s shadow, meeting the woman who would normally in this sort of movie be his wife but whom he shows no interest in. We see his triumphs, his gumption, his naïveté; we know he will be screwed, but we never really see how or why or by whom. We see his genius and its turn to madness, but the turn is abrupt rather than slow, leaving us to feel as though we’ve missed a big chunk of the movie. We watch a tale epic in scope, traversing from New York to the world’s fair in Chicago to the mountains of Colorado, but we’re cheated of any grandeur by Almereyda’s (or, more likely, the budget’s) decision to substitute green screens for sweeping vistas or churning train stations.

It’s the aforementioned asides—the cutaways to Google search results narrated by Anne Morgan (Eve Hewson) in period costuming and a brief moment where Edison (Kyle MacLachlan) turns away from a conversation we’re informed never took place in order to pull out an iPhone and start scrolling—that stand out, and your patience for this sort of meta-cleverness will, ultimately, be what allows you to get through this without rolling your eyes and switching to something else. Ironically, it’s film—a relative of the kinetoscope invented by Edison—that tells us Tesla’s story, and it’s the tools and tricks of film that break the fourth wall and are used to imply that we live in Tesla’s, not Edison’s, world.

History is written by the victors, to be sure. But it’s rewritten—occasionally quite poorly, and in a way that offers us little genuine insight into the subject being rehabilitated—by the filmmakers.

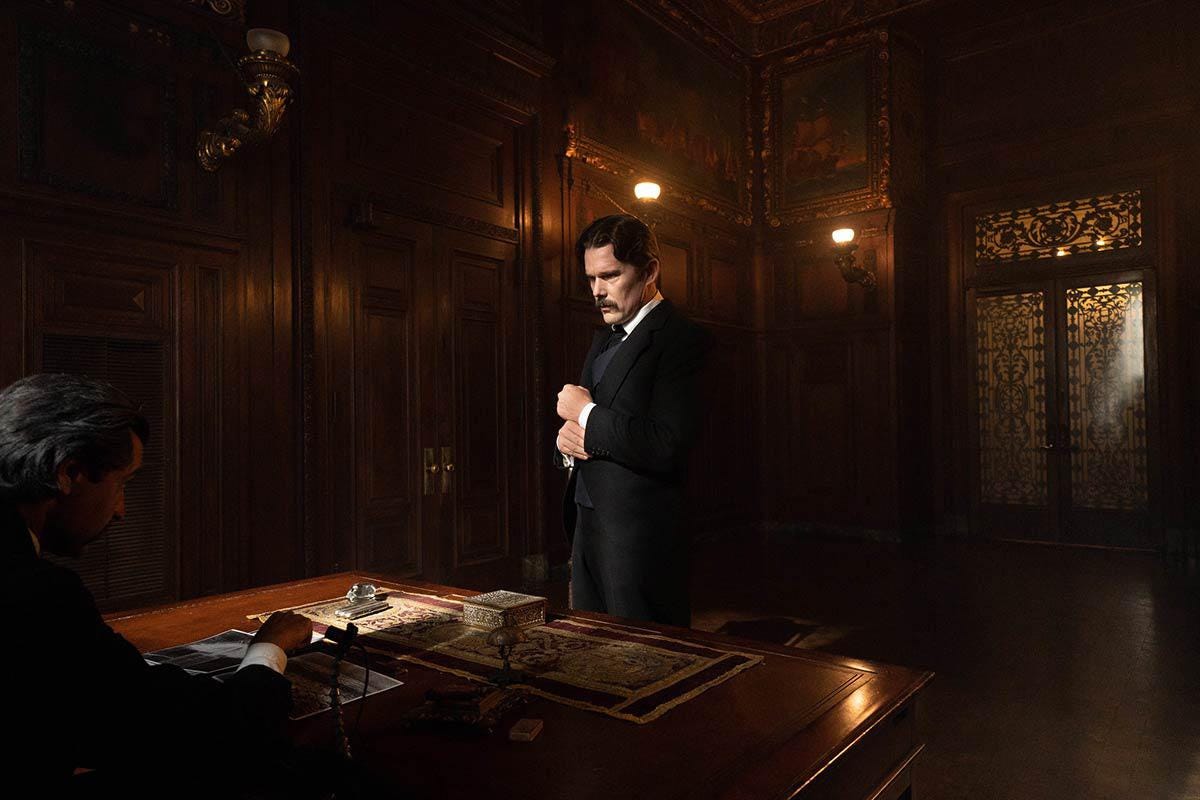

The only reason I can’t dismiss Tesla out of hand is the power of the performances. Ethan Hawke as Tesla brings to bear that look of confused intensity he has made his most powerful tool in recent years, and it’d take a heart of stone not to appreciate how hard he commits to the ridiculous nonsense Almereyda asks of him in the film’s closing moments. MacLachlan, meanwhile, looks as though he’s having a grand time playing the Wizard of Menlo Park, and Jim Gaffigan is a goofy delight as an affable, lemonade-swilling George Westinghouse.

Assigned Viewing: The Prestige (VOD, Blu-ray)

Speaking of Nikola Tesla! David Bowie’s turn as the scientist/magician is one of the highlights of The Prestige, Christopher Nolan’s movie about dueling magicians whose shenanigans escalate to murder.

The Prestige is a movie about movies, insofar as it is a movie about the three-act structure: the pledge, the turn, and the prestige, as Cutter (Michael Caine) explains. But what makes it sublime is the horrifying truth to the trick at the heart of the movie, the secret that winds up condemning one man to death and another to repeated death. It’s a reminder that the rules we live by provide a certain amount of structure, and when you break those rules—when you go outside the bounds of what is morally acceptable and scientifically allowed—the end result is, actually, quite terrifying, even grotesque.

Magic is only fun because it isn’t real. If what we were watching were real, we’d all go running from the theater, screaming in terror, denouncing those who have transgressed against morality.

As I said: The Prestige is a movie about movies.

I'm always right, as those who follow me on Twitter already know, but I'm also happy to hear from people who are wrong. If you have questions, comments, or complaints, drop me a line by responding to this email. And if you're tired of hearing from me, just click on that "update preferences" button at the bottom of this missive. —SB