A Brief History of Media and Audiences and Twitter and The Bulwark

Elon Musk didn’t attack Substack. He went after the subscription model for journalism.

1. Twitter and Media

I am sorry that we have to talk about Twitter and Elon Musk. Truly. But it’s of some importance to The Bulwark. So I want to include you.

By now you may have read that late last week, Musk decided to go to war with the platform Substack, where we publish this newsletter. If not, you can read Cathy Young’s summary here.

What I want to talk about isn’t the macro, but the micro: I want to talk about how Twitter relates to The Bulwark and why this incident is important for us.

I don’t like Twitter. I understand that the platform has some upsides and can produce occasional good outcomes. You can make real friends on it and use it to do good things. But—and this is my own view—in the full accounting, the balance goes the other way. Twitter takes more out of you than you take out of it.1

The inherent tension for writers is that whatever Twitter costs you personally, it’s quite valuable to your professional life.

In the old days—and here I mean even as recently as 2000 or 2004—audiences were built around media institutions. The New York Times had an audience. The New Yorker had an audience. The Weekly Standard had an audience.

If you were a writer, you got access to these audiences by contributing to the institutions. No one cared if you, John Smith, wrote a piece about Al Gore. But if your piece about Al Gore appeared in Washington Monthly, then suddenly you had an audience.

There were a handful of star writers for whom this wasn’t true: Maureen Dowd, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion. Readers would follow these stars wherever they appeared. But they were the exceptions to the rule. And the only way to ascend to such exalted status was by writing a lot of great pieces for established institutions and slowly assembling your audience from theirs.

The internet changed everything.

The change wasn’t immediate, but its inevitability was immediately obvious. The internet stripped institutions of their gatekeeping powers, thus making it possible for anyone to publish—and making it inevitable that many writers would create audiences independent of media institutions.

You know how it went from there: The internet destroyed the apprenticeship system that had dominated American journalism for generations. Under the old system, an aspiring writer took a low-level job at a media institution and worked her way up the ladder until she was trusted enough to write.

Under the new system, people started their careers writing outside of institutions—on personal blogs—and then were hired by institutions on the strength of their work.

Or, at least that was the idea.

In practice, these outsiders were primarily hired not on the merits of their work, but because of the size of their audience.

Because when the internet destroyed the gatekeeper function, what it really did was transform the nature of audiences. Once the internet existed it became inevitable that institutions would see their power to hold audiences wane while individual writers would have their power to build personal audiences explode.

As a matter of business, this meant that institutions would begin to hire based on the size of a writer’s audience. Which meant that writers’ overriding professional imperative was to build an audience, since that was the key to advancement.

Twitter killed the blog and lowered the barrier to entry for new writers from “Must have a laptop, the ability to navigate WordPress, and the capacity to write paragraphs” to “Do you have an iPhone and the ability to string 20 words together? With or without punctuation?”

If you were able to build a big enough audience on Twitter, then media institutions fell all over themselves trying to hire you—because they believed that you would then bring your audience to them.2

Established writers flocked to Twitter because, as Walter Bagehot observed, once financial leverage exists for anyone, everyone must use it just to stay at par. If you were a writer for the Washington Post, or Wired, or the Saginaw Express, you had to build your own audience not to advance, but to avoid being replaced.

For journalists, audience wasn’t just status—it was professional capital. In fact, it was the most valuable professional capital.

If you were a young writer and a genie gave you the choice at the start of your career to either have family friends in high places, the ability to write like Mencken, or 500,000 Twitter followers, I can tell you right now that the Twitter followers would be the one to pick.

Which is why journalists have been so loath to leave Twitter, even as they’ve watched the platform devolve.

Everything we just talked about was driven by the advertising model of media, which prized pageviews and unique users above all else. About a decade ago, that model started to fray around the edges,3 which caused a shift to the subscription model.

When media institutions began creating direct relationships through their readers, rather than trying to monetize their readers to third parties, this shift began to lessen the importance of social media platforms, especially Twitter—because in subscription economics, audience volume matters less than product value.

Today, if you’re a subscription publication, what Twitter gives you is growth opportunity. Twitter’s not the only channel for growth—there are lots of others, from TikTok to LinkedIn to YouTube to podcasts to search. But it’s an important one.

Which is why so many journalists freaked out this weekend—and not just journalists on Substack.

Because Twitter’s attack on Substack was an attack on the subscription model of journalism itself.

And since media has already seen the ad-based model fall apart, it’s not clear what the alternative will be if the subscription model dies, too.

Okay—we’re finally ready to talk about The Bulwark.

When we started The Bulwark, it wasn’t a business, it was a mission. We wanted to save democracy; business model TBD.

We launched Bulwark+ using Substack not quite on a lark, but certainly not as part of a grand plan. It was an experiment and it has succeeded beyond our fondest hopes because of you guys. You came together to support this thing of ours for lots of different reasons, but primarily because you wanted something like The Bulwark to exist in the world.4

Because of your support, I’m fairly certain that The Bulwark would be okay if Twitter re-decides to unperson Substack. It might slow our growth to a degree that we’d notice it. (Though having spent the weekend looking through analytics, I’m not certain of that.) But we’d be okay.

Other institutions that rely more heavily on Twitter for growth might not be. And since I’m a big champion of subscription media,5 that concerns me. A lot.

All of which is why having a major social media platform run by a capricious bad actor is suboptimal.

And why I think anyone else who’s concerned about the future of media ought to start hedging against Twitter. None of the direct hedges—Post, Mastodon, etc.—are viable yet. But tech history shows that these shifts can happen fairly quickly.

For starters, I’d suggest that you consider using the Substack app.

Substack rolled this out several months ago and I avoided mentioning it until I’d spent a lot of time kicking the tires. And I have to tell you: It’s fantastic. It’s now my preferred way for consuming all of the many (many) newsletters I read.6 Just a fantastic reading experience. You can get it the iPhone/iPad version here or the Android version here. (See my note in the footnotes about your email preferences.)

If you like getting stuff from YouTube, our channel over there is growing pretty well. Maybe subscribe? If you’re into that sort of thing? (Every Sunday we post video of our new Next Level show—this week Tim and I interviewed Frank Bruni. It was great.7)

There’s also a Bulwark subreddit: r/thebulwark.

Finally: Substack is rolling out its own Twitter clone, called Notes. I’m going to kick the tires on that for a bit. I’ll let you know how it is later this week.

Thanks for being with us and making The Bulwark possible.

2. My Gift to You

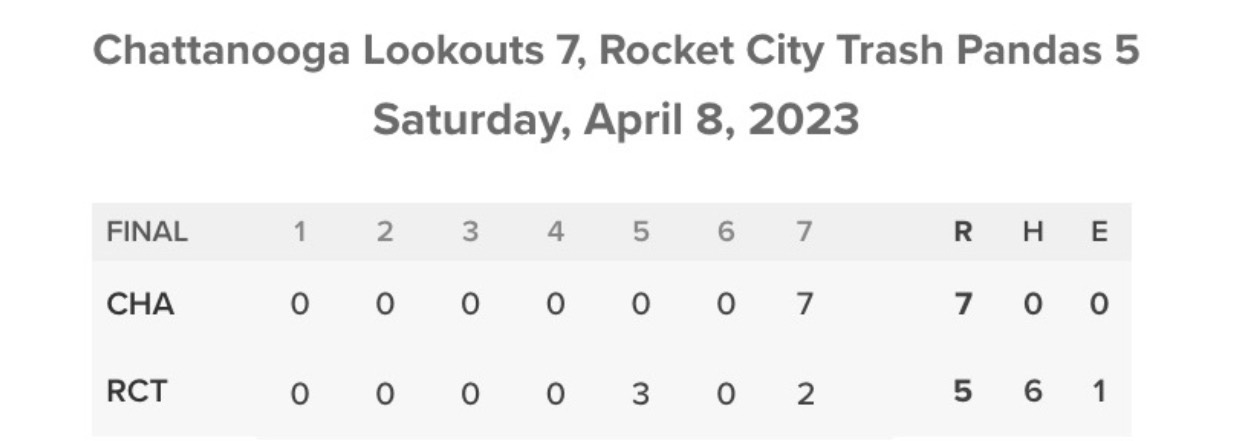

Take a look at this minor league box score from Saturday and tell me what’s wrong:

That’s right. A 7-run 7th inning on . . .

Zero hits!

This result was so crazy I had to chase down the game recap:

Yes, the Trash Pandas pitchers threw a collective no-hitter but also coughed up seven runs. Amazing and ridiculous. How did that happen?

It was actually a seven-inning game (as all minor-league doubleheader games are) and the Trash Pandas had a 3-0 lead heading to the seventh. The Lookouts then went ...

Walk

Walk

Pop out

Walk

Strikeout (it's still 3-0 with one out left in the game!)

Walk

Error, two runs score

Hit by pitch, loading the bases with a 3-3 tie.

Hit by pitch

Hit by pitch (yes, again)

Walk

Wild pitch, running the score to 7-3.

Hit by pitch

Strikeout

Five hitters drew a walk, four hitters were plunked and one reached via error. What a catastrophic inning for the Trash Pandas, who did manage to tack on two runs in the bottom of the seventh for the 7-5 final score.

Coleman Crow was the starter for the Trash Pandas and allowed only two walks in six scoreless, hitless innings, and the bullpen -- and defense -- totally fell apart after he left the game.

This game. It’s so good that the owners can’t ruin it, no matter how hard they try.

I’m going to smile all day thinking about that box score.

3. Instagram Face

I don’t do Instagram—at all. Which means that I have a gigantic blind spot in my understanding of American culture. (Here I should mention The Bulwark does have an Instagram account that you can follow—but full disclosure: I don’t.) Anyway, this piece was helpful to me:

At a restaurant in Miami last month, dining beside my husband, I examined the women around me for what people refer to as Instagram Face. The chiseled nose, the overfilled lips, the cheeks scooped of buccal fat, eyes and brows thread-lifted high as the frescoed ceiling. Many of the women had it, and thus resembled each other. But not all of them. Not, for example, me.

Critics call this trend just another sign of our long march toward a doomed, globalized sameness. A uniform suite of cosmetic procedures, popularized by social media, apps and filters, accelerated by both natural insecurity and injectables’ dropping costs. One by one, they hint, women will give in and undergo them. Until we all look identical, just like our restaurants do, and our hotels, and our airports, in our creep toward homogenization which we’ve somehow mistaken for a worthwhile life.

They’re wrong, because in their focus on uniformity, they’ve forgotten the premise of cosmetic work in the first place. Distinction. Good face, like good taste, has a direction: downward. The success of Instagram Face, its ubiquity, isn’t the start of cyborg aesthetics. It’s the end of it. Because what might save us from such apocalyptic beauty is something almost too ugly to say out loud: When in history have rich women ever wanted to look like regular ones?

Kylie Jenner is widely considered the face that launched a thousand fillers. The reality star did her lips in 2014, and seemingly everything else soon after. If you believe social media, the model Bella Hadid covered Carla Bruni’s features like a singer does another’s song. Emily Ratajkowski, the extended Kardashian cast: Each began to modify herself until as if in some joint experiment they arrived at an aesthetic congruence. Their platonic ideal was an ethnically ambiguous woman, neotenous from the neck up, hypersexual from the neck down. Her whole schtick is that she looks unlikely to know who Plato is. That way when Emily, who is both a model and an essayist, seems likely to have read him, she gets not only your desire but also the delicious gotcha of having been misjudged.

Captured on Instagram grids, TikToks, and Snapchat stories, analyzed in duplicated miniature the world over, the gradual alterations of these famous faces became undeniable. And so, at least partially, they gave up denying them. Kylie confessed to her lips. Bella, much later, to her nose job. Filters, like “fox eyes” or “perfect nose,” permitted young women to try on, like hats, these features, just as it became increasingly normalized to go out and get them. Cosmetic surgeons advertised their noninvasive, or “reversible” work on viral videos. The changes harbored a new life. Women learned that, if they were beautiful, they could make ludicrous money just existing online. The price of Botox dropped by 27% over two decades, as the price of seemingly everything else went higher.

Bad for your mind. Bad for your soul. Bad for your productivity. Bad for your understanding of the world around you. I could go on and on.

Which was the exact inverse of the old days, when the New York Times op-ed page could have charged writers for the privilege of appearing on their pages rather than paying writers for their work.

Again, this was inevitable. The ad space on the internet is expanding to infinity. Infinite ad inventory = downward pressure on ad prices.

I’m fortune-telling here, but it’s based on several thousand emails and conversations.

I write an entire newsletter every Saturday introducing people to great newsletters.

If you decide to use the mobile app, be sure to pay attention during the initial setup so that you don’t unintentionally turn off emailed newsletters. We’ve heard from some members that they did this by mistake. You can always check your email preferences at plus.thebulwark.com/accout.

You’ll like the Easter Egg in the bottom-left corner of my box.

"When we started The Bulwark, it wasn’t a business, it was a mission. We wanted to save democracy; business model TBD."

This is a philosophy of life. Whatever you do, do it because it's worth doing in itself. Then . . . "business model TBD."

By the way, that this ethic dominates The Bulwark has been obvious from the start.

Initially, the reason I joined The Bulwark was simple. I wholeheartedly agree with the motto of WAPO. "Democracy dies in the dark." You folks were, and still are, my light. I mean it.

I have conversations with each of you, in my head (I'm not psychotic, I just double check my thinking). If my JVL voice says I'm on target. I probably am. But if Ms. Longwell pops in and tells me I'm too cynical, I try to soften my stance. Charlie? His voice teaches me new curse words and phrases. Right now, 'fuckery' is on my play list.

I subscribe to you because I need you to help me understand all this fuckery that's going on in our psychotic country. Y'all are my water wings when I think drowning is imminent.