Everyone’s Favorite Slopulist Scapegoat

Trump and populist Dems have linked arms to “fix” the housing crisis.

FOR MAGA REPUBLICANS, the root cause of every problem is immigrants. Populist Democrats, by contrast, prefer to scapegoat billionaires and Big Business.

But lately, President Donald Trump has started to bogart Democrats’ favorite villains, too, by casting them as the baddies conspiring to increase housing costs. There’s now bipartisan (and yet wrong) agreement that Wall Street’s “institutional investors” are to blame for high home prices, and Congress appears on the verge of making the problem worse.

Here’s the background: Trump has struggled to address Americans’ affordability concerns. Calling the whole thing a “hoax” didn’t work. His administration frequently blames immigrants for high prices, especially when it comes to homes. (“Want affordable housing?” DHS tweeted. “Help report illegal aliens in your area.”) Yet somehow, even as the administration claims to have deported hundreds of thousands of immigrants, prices still aren’t going down. In fact there’s reason to believe that house prices could rise faster than they otherwise would, because Trump is effectively shrinking the homebuilding labor force.1

So the president has pivoted.

Last month, Trump announced that his new solution for the housing affordability crisis would be banning “institutional investors” from owning homes. He is now demanding that Republicans in Congress add an amendment to their housing bill to enforce the ban, reportedly with language that would allow the treasury secretary to define or exempt institutional investors as he sees fit. “Neighborhoods and communities once controlled by middle-class American families are now run by faraway corporate interests,” Trump wrote in his executive order. “People live in homes, not corporations.”

If this sounds like the kind of thing you might hear progressive Democrats say, that’s because it is.

For years, progressives have argued that the real reason that prices are high is that Wall Street firms are gobbling up all the homes. It’s a compelling narrative with terrific optics: Politicians naturally want to be seen as standing up for the little guy against big, bad, greedy corporations.

Unfortunately, the story happens to be wrong.

First let’s define our terms. “Institutional investors” typically refers to landlords who own at least a thousand housing units. And it is true that in the aftermath of the 2008 housing bust, when foreclosures skyrocketed and there was a surplus of housing, some big Wall Street institutions (such as Blackstone) did swoop in to the market and buy lots of homes on the cheap. This was, and remains, controversial. They didn’t buy these homes to bulldoze them, of course; they bought them to rent them out. Which they did, and some continue to do.

But today, institutional investors hold a teeny share of single-family housing: roughly 3 percent of single-family rentals, and around 0.5 percent of all single-family housing stock (i.e., rentals and owner-occupied housing together). To be clear, there are a lot more homes that are owned by “investors” of some kind—people other than the primary occupant. Most of these investors, though, are mom-and-pop landlords who own fewer than ten properties, not the big “institutional” investors that politicians want to boot from the market.2

Even in markets with a higher concentration of institutional investor–owned homes, the share is still pretty slim. For example, the most concentrated markets are Atlanta and Jacksonville, and in each place big corporate investors hold about 3 percent of single-family housing stock, according to the real estate data platform BatchData.

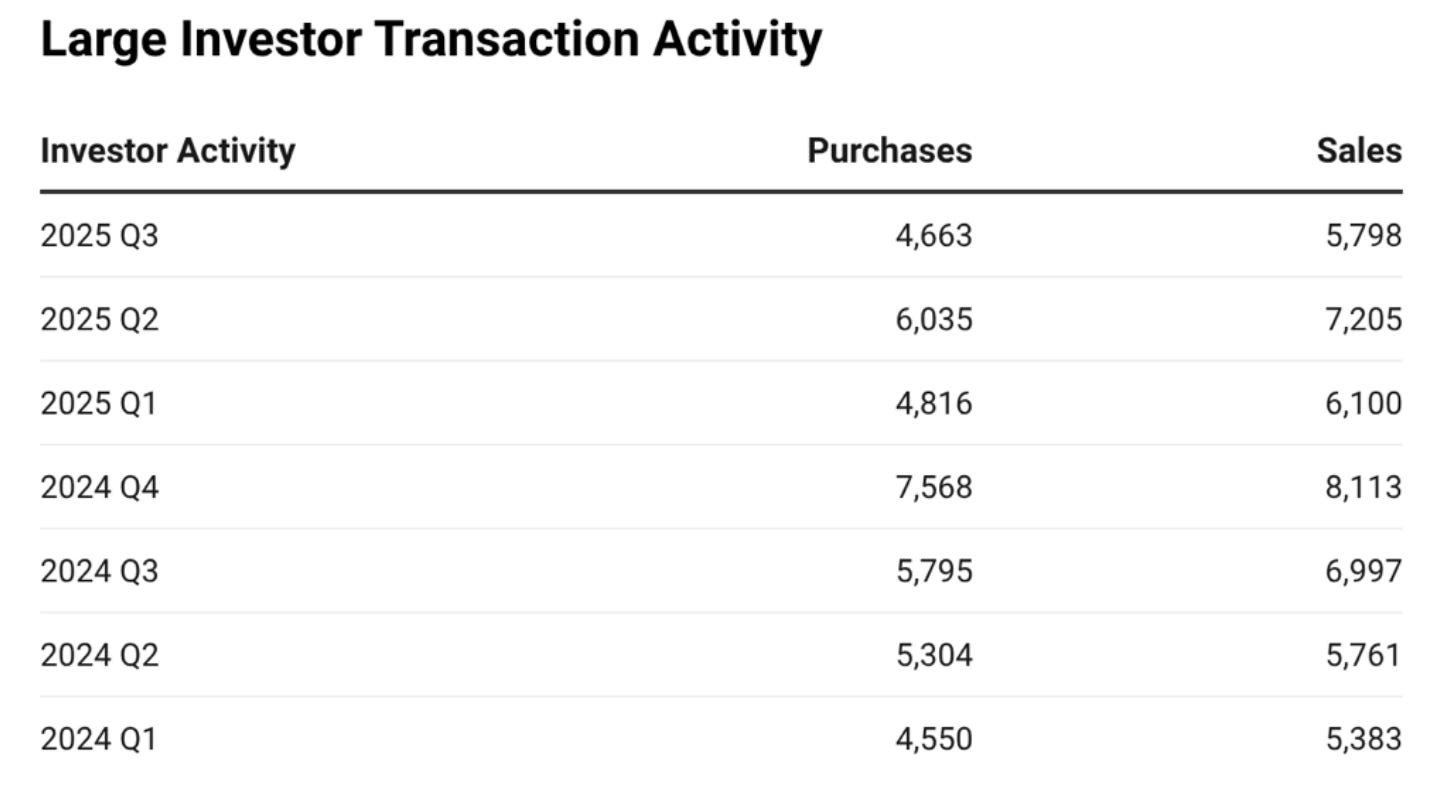

What’s more, institutional investors have largely been reducing their holdings. For the past seven consecutive quarters, large institutional investors have been net sellers of single-family homes. For example, in the third quarter of 2025, they sold 5,798 homes while purchasing only 4,663.

They’re not getting out of the housing market entirely; rather, they’re shifting their capital to build new housing instead of buying up existing housing stock. “Institutional players continue their strategic pivot, deploying capital into build-to-rent projects, adding inventory rather than competing with traditional homebuyers for existing inventory,” according to BatchData.

The upshot is this: If Congress bans institutional investors from owning homes, at best it will probably have no effect on housing costs for normal people. At worst, it could raise costs, at least in rental markets where these mega-investors might have otherwise added more housing stock.3

Actual fixes to housing affordability are complicated. They involve zoning, construction costs, permitting and regulatory reform, and other eye-glazing issues.4 They also sometimes ruffle the feathers of important political constituencies.

For example, there are the NIMBY homeowners5 whose retirement savings are tied up in their home equity, and who therefore don’t want to see the housing supply grow and housing prices fall. Hence Trump’s recent, puzzling assertion that he’s going to make housing more affordable but also somehow more expensive. (“People that own their homes, we’re going to keep them wealthy. We’re going to keep those prices up. We’re not going to destroy the value of their homes so that somebody that didn’t work very hard can buy a home.”)

Clearer thinking.

Better ideas.

And a growing pro-democracy community.

Become a Bulwark+ member today.

Blaming Big Bad Corporate Interests is easier than advocating policies that might alienate NIMBY boomers or trying to streamline permitting bureaucracies. So you get a lot of demagoguing, with little effort to understand, explain, or solve the very real problem of burdensome rents and would-be homebuyers being locked out of the market. Unfortunately, it’s hard to write the right prescription if you get the initial diagnosis wrong.

You know how you can tell these politicians may not have thought this through? They can’t even keep straight the names of the companies they want to ban. Vice President JD Vance gets this wrong all the time, leading an unrelated firm that doesn’t own any single-family homes to release pleading statements each time it gets mistakenly namechecked. Is the big bad villain supposed to be Blackstone? BlackRock? Blackwater? Something black, for sure.

Ramparts

— Another slopulist housing policy that has gained support in the past year (and that economists almost uniformly hate) is rent control, which has been finding adherents in New York City, Los Angeles, and Boston, among other places. I’ll probably write a future newsletter on this topic.

— Trump is threatening to block the opening of a new bridge between the United States and Canada. This would be very bad for the U.S. auto industry, which sends goods back and forth across the existing, privately owned bridge daily. Note that the guy who owns the existing bridge has also personally been lobbying Trump to prevent competition: He met last week with Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick the same day Trump started his bridge-posting campaign. Democratic lawmakers seem to have noticed. Watch this space.

— National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett says that Fed economists should be punished for a paper finding that Americans bear most of the cost of Trump’s tariffs. “The people associated with this paper should presumably be disciplined,” Hassett said, “because what they’ve done is they’ve put out a conclusion which has created a lot of news that’s highly partisan based on analysis that wouldn’t be accepted in a first-semester econ class.” I wonder what he would say about an economist who predicted COVID deaths would fall to zero in May 2020 using an Excel function.

— JPMorgan Chase is reportedly in talks to become the banker for Trump’s “Board of Peace,” the institution meant to rebuild Gaza/rival the United Nations/provide a personal slush fund for the president. Just coincidentally, Trump sued JPMorgan last month for $5 billion for “debanking” him.

— Last year Trump pardoned the founder of Binance, Changpeng Zhao, who had been convicted of money laundering. Now Binance holds 87 percent of Trump’s stablecoin. Another crazy coinkydink.

— This story has everything: Grift. Immigration. Ron DeSantis. Toilets. A corporate phone number that (intentionally) spells out the word “POOP.” “$92 million for porta-potties? Big spending at ‘Alligator Alcatraz’.”

There’s reasonable debate about whether Trump’s mass deportations are likely to push overall inflation up or down on net, since immigrants are both producers and consumers in the U.S. economy. That is, they make stuff other people buy, and they also buy stuff that other people make. But for certain industries that are disproportionately reliant on foreign-born workers, deporting the workforce is likely to cause higher prices and/or shortages. Think: food, childcare, and yes, housing.

This is one source of confusion in coverage of this topic: People hear a high figure for the share of “investors” who buy homes and think that “investors” means “big companies.” Mostly, it’s smaller landlords. Another frequent mistake is conflating single-family rentals with all single-family homes.

There may be a carveout for build-to-rent housing in whatever bill ultimately makes it through the House, which would limit the bill’s damage to the housing market. But then again: What problem are we trying to solve here?

The best explainer of these issues is Jerusalem Demsas.

This will probably come as no surprise, but it turns out that one of the best-known promoters of the “institutional investors drove up home prices” claim happens to be someone who has blocked housing development in his neighborhood.

You’ve crossed an important line: using the verb “bogart”. I love you.

What about apartments? What market forces are keeping them unaffordable, and preventing new construction? Another article, please.