A Different Kind of Trump

Caring for a son with severe disabilities has given Fred Trump III a clear-eyed view of the politics of health care.

IT’S NO SURPRISE THAT DONALD TRUMP’S so-called health care “plan” is a skeletal ten-paragraph document (nineteen if you include the fact sheet). Or that it is nowhere near “great,” though that word is part of its official title, capitalized and italicized.

Fred Trump III, Trump’s nephew, was among the least surprised. “It’s a joke, of course,” he told me last week on Zoom. “You need serious people” to get things done on health care, he added, and there aren’t many around.

To be fair, lawmakers in both parties are on track to maintain current levels of science spending and in particular to reject the president’s proposed 40 percent cut in biomedical research. But in general, between ideology, budget constraints, and the time it takes to turn a bill into a law, progress is hard to come by—as Fred III and his wife, Lisa, are all too aware.

Their third child, William, born in June 1999 with a rare genetic seizure disorder caused by a mutation in the KCNQ2 gene, is nonverbal and uses a wheelchair that he can’t move by himself. Now 26, he lives near his parents in a state-run group home that provides the round-the-clock care he has needed all his life.

Lisa and Fred have had to be serious about health care and advocacy—for their own child and beyond. They have focused on research, prevention, and treatment, caregiver training and pay, housing options for people with disabilities, and more use of data to shape research and services, as well as helping other parents handle challenges they never anticipated. Their own experiences through the years, with both relatives and politicians, suggest it’s best to keep expectations tempered.

One Disappointment After Another

Soon after William was born, Fred and Lisa got involved with a stem-cell research organization. They thought at the time that this could be “the potential miracle cure,” Fred told me. But then, for “theological reasons,” as Fred put it, President George W. Bush sharply limited the research. “That of course was very damaging,” he said.

Bush’s move, in his view, was similar to what’s happening now. He and Lisa described hearing firsthand about the impact of the Trump administration’s medical research cutbacks—project terminations and brain drains to countries like Canada, Ireland, and China—from scientists and others at a KCNQ2 Cure Alliance conference in September.

“Putting my businessman hat on, I don’t know what they’re thinking,” Fred said of the decisions to pull back on research. People with disabilities “are going to be in our lives for as long as they’re going to be in our lives. If they get sick or ill or you don’t take advantage of what’s out there to help them . . . they’re going to need everything that goes with having a severely disabled person in your life. As opposed to spending the money now” to try to head off problems early in their lives.

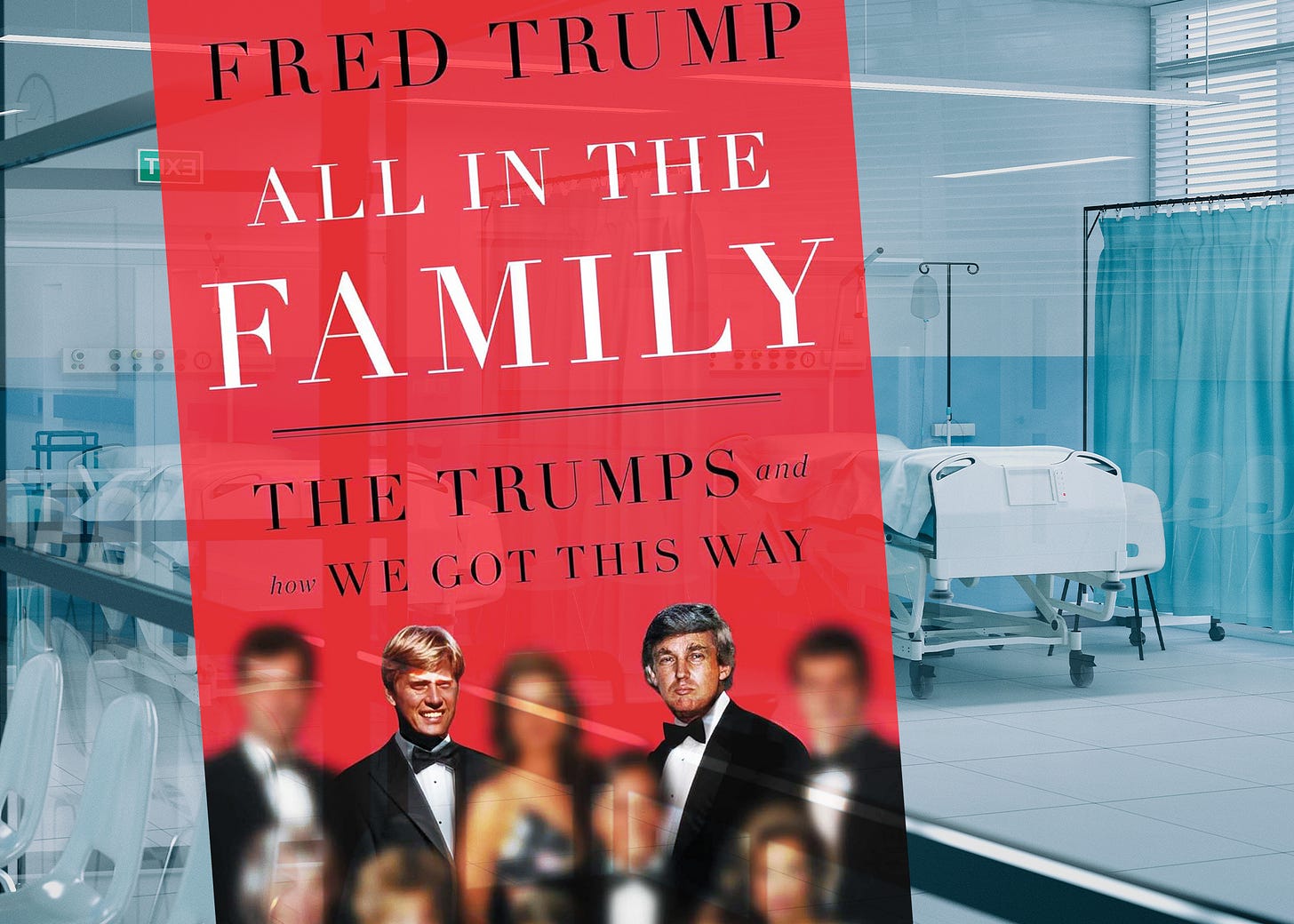

In his July 2024 memoir, All in the Family: The Trumps and How We Got That Way, Fred III wrote that he and his fellow disability advocates did find common ground in his uncle’s first term with several top officials and the president himself with an idea for a program “that would cut through the bureaucracy and control costs and also yield better and more efficient medical outcomes.” Did anything concrete come out of those meetings? “Sausage-making in government is a very long process,” he said. “So to answer your question, no, nothing we were involved in came to fruition.”

In 2016, Fred had privately voted for Hillary Clinton. He appreciated that she “stood up for the fifty-six million ‘invisible voters’ with disabilities.” Unfortunately, he wrote in his book, “those statements were too quiet as Donald outworked, outhustled, and out-steamrolled her.”

Fred Trump voted in 2020 for Joe Biden, who also shared some of his priorities—among them investing in home-based care for seniors and disabled people. The House passed that provision in Biden’s original Build Back Better Act, but it was left out of the renamed “Inflation Reduction Act” that Biden eventually signed—a casualty of nearly two years of sausage-making.

The Road Not Taken

Nine days after Biden abruptly dropped out of the 2024 race, with the July 30 publication of his book and a raft of interviews to promote it, Fred Trump went public as a Democrat and “a different kind of Trump.” By then, Vice President Kamala Harris was the Democratic nominee-in-waiting, and she soon pledged in her platform to expand Medicare coverage of home care for seniors and disabled people.

Fred, in a September 4 appearance on CNN, offered to campaign for Harris “if I’m asked.” He also noted that he had personal ties to two swing states: Michigan (his mother was born in Kalamazoo) and Pennsylvania (he, his father, and his older son, Cristopher, attended Lehigh University in Bethlehem, and he has family in the state).

It is not unheard of for relatives to denounce politicians in their family. The Gosars made ads in more than one campaign against their brother Paul—a MAGA House member from Arizona—even though they knew he would almost certainly win re-election in his conservative district. The Kennedys have tried for years to block the rise of anti-vaccine conspiracist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to save their family legacy and protect the country from his ideas. They spoke out forcefully against his 2024 presidential campaign, his endorsement of Trump, and his appointment as health and human services secretary, and in September called for him to resign the post. Nothing has worked.

What about a national race involving several closely fought swing states? Fred Trump talked his way into the Democratic convention, but he was not invited to speak. Nor did he end up campaigning for Harris—even after he wrote to her, he told me, and Lisa wrote to Gwen Walz (first lady of Minnesota and mother of a son with a nonverbal learning disorder), saying “here we are, we’ll give it our all.” The letters, he said, were met with silence.

“It was deemed not the right move for me to speak or to really get involved in the campaign at all,” Fred said. “As a political junkie, I thought that was a very bad move.”

Could Fred and Lisa have helped Harris win? Maybe. Fred would have been a new Trump publicly taking on the Trumps. His younger sister Mary, a clinical psychologist and author of 2020’s much-discussed Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man, had forged the tell-all path at a time when Fred III disapproved. She told NPR she’d vote for Biden in 2020, and four years later joined his spin-room team for the fateful June debate with her uncle.

Now Fred was ready to help Harris, from his perspective as a real estate executive, a father who had faced a terrifying test with his third child, who had become an advocate for William and people with disabilities, and who would have worked to mobilize them and their supporters.

My own instinct, at least in hindsight, would be to try anything, to throw everything at the wall, make a bet on novelty and counterintuition in an attention economy. That said, Harris was a risk-averse candidate plunged into an abbreviated campaign on a compressed time frame—not a recipe for throwing in with the latest Trump family rebel.

‘Bless the caregivers that take care of my son’

As Fred wrote in his book, the Trump name had been “a double-edged sword” as far back as 1995 and as recently as 2021. He got kicked out of his high-level job at Cushman & Wakefield that year after the January 6th Capitol riot, when the real estate services firm severed all ties with the Trump Organization. “Cushman was now a Trump-free zone, including no more me. I could change a lot of things, but I couldn’t stop being a Trump,” Fred said in his book.

The name was not only toxic in the work world—even his fundraising efforts for groups helping people with disabilities “had gotten tough because of Donald,” he wrote. Especially after Donald imitated a reporter with a disability in 2015. It was not an aberration. Trump’s idea of a Thanksgiving social post ten years later was to call Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz “seriously retarded.”

In between came Fred’s memoir, and two quotes from it that made headlines (though a Trump campaign spokesman called them “completely fabricated and total fake news”).

One came after a constructive White House meeting Fred had arranged for disability advocates. He wrote that his uncle seemed supportive, but then said: “Those people. . . . The shape they’re in, all the expenses, maybe those kinds of people should just die.” The second came a few years later, on a call with Fred about William’s medical expenses after Trump had left office: “I don’t know. . . . He doesn’t recognize you. Maybe you should just let him die and move down to Florida.”

Fred wrote that he was appalled but tried to keep his cool. “No, Donald,” I said. “He does recognize me.” In a section about William’s life as a young adult, he said his son loves swimming and music, watches sports with his brother, and communicates with his “heart-melting blue eyes.”

The same day his uncle used that R-word, Fred posted his own holiday greeting: “Happy Thanksgiving to all, and bless the caregivers that take care of my son William and the millions of disabled (determined) in our country. They deserve better pay, and our gratitude.”

Indeed, a different kind of Trump.