The Assault on Los Angeles Brought Jorge Ramos Back

After a half-year away from journalism, the former longtime Univision reporter and anchor is one of many Hispanic journalists rushing to tell the story.

THE LOS ANGELES ICE PROTESTS have revealed a little-understood dimension of mass deportation and the social reality of many Hispanic communities.

In certain areas, immigrants have become so embedded in the culture that it is only natural for them to fight for the garment workers and day laborers who are their families, friends, and neighbors. They are reflexively drawn to the crisis, and they feel a sense of empathy and compassion for those on the receiving end of the belligerence of an overly aggressive federal government.

Those instincts are apparent among Hispanic journalists, too, many of whom have flocked to Los Angeles to capture the heartbreaking images that are emerging from the ongoing protests and violent confrontations.

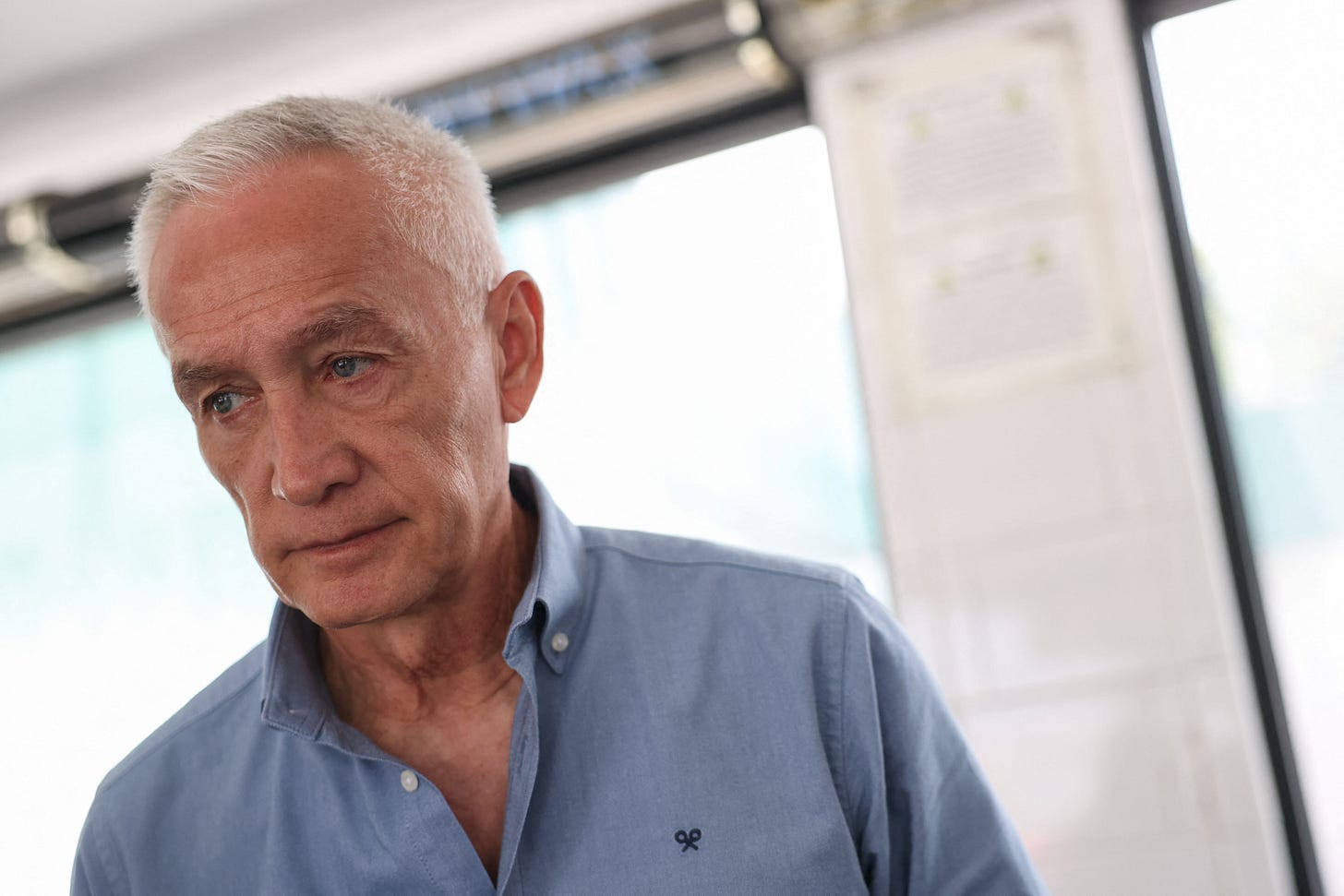

The story has had such a magnetic draw that it even lured one of the most famous Hispanic journalists back into action.1 This past week, Jorge Ramos, the legendary newsman who had been keeping a low profile since leaving Univision at the end of last year, has been on the ground in L.A.

“This is the exact moment to return,” he explained in a post on Instagram. Ramos went on to call the situation in the country “grave” and said that while violence needed to be avoided, he felt compelled to tell the story of why so many immigrants feel hunted and betrayed.

And he’s telling it. In a relatively short time on the ground, Ramos spoke to labor activist Dolores Huerta. He asked women about their fears of being out protesting amid the threat of violence, only for them to reply that they weren’t afraid—they were pissed. He interviewed Maria Alvarado, the mother of Roberto Sandoval, a U.S. citizen who was caught up in a worksite raid by ICE on Sunday and detained. Her son was driving his work truck in through the facility gate when he was surrounded by five ICE vehicles. Asked if her son had told them he was an American, Alvarado said the agents didn’t let him speak.

Ramos’s work has been primarily disseminated through social media, but he has upcoming plans to return to more traditional media in a more permanent way, he told me.

I spoke to Ramos Wednesday. He told me he came to L.A. for the first time in January 1983. The city has been through a lot since then, but even so, he says he has never seen levels of fear like this. At the time we talked, he had just visited a park where children were celebrating the end of the school year; some parents kept their kids home, afraid of what could happen. Immigrants and Latinos are increasingly wary of going to hospitals, going to work, and dropping their kids off at school, he relayed.

“But I also found an incredibly brave city,” he added. “A Latino city, speaking for others, that is being incredibly brave and courageous.”

This newsletter covers challenging, emotionally charged subjects—such as the realities of life for immigrants in a country increasingly hostile to them—but Huddled Masses has never been about sensationalism or doomerism. It’s about keeping you informed, with a clearer sense for the stakes and complexities of the subject.

We’re all about seeing around corners at The Bulwark. If you’re not already a member, please consider signing up. You’ll be supporting our work—and we bet you’ll find it improves your situational awareness in this fraught moment.

Much of the nation’s understanding of what is happening in L.A. has been refracted through the prism of traditional and social media reports, where scenes of violence, confrontation, and politics predominate in users’ feeds.

Hispanic journalists’ coverage of the crisis has gone against these tendencies. If you follow channels like Univision and the accounts of journalists such as Ramos, or even the LA Times Food accounts on social media, you are more likely to see Latino restaurant workers using milk to rinse tear gas out of the eyes of sheriff’s deputies in Compton, street vendors ducking behind their food stands during dangerous moments, and others pouring milk from their agua frescas into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters.

Ramos may be the most famous name providing this content. But as I took stock of the work being done, I quickly realized that many of the Latino journalists on the ground—braving the danger of rubber bullets and noxious clouds of chemicals—were women.

Claudia Carrera with Univision in Los Angeles filed a report from Santa Ana amid loud explosions from nearby fireworks; she also posted a video of her and her photographer’s SUV having its window blown out by a rubber bullet from the Santa Ana police department. During that report, she interviewed a young man of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent wearing a Los Angeles Dodgers cap and a suit and tie. (He had come to the protest straight from work.) He told her that as the son of a parent who arrived in the United States without papers, he was personally affected by the immigration crackdown. He wanted Americans to hear alternative voices.

Nidia Cavazos from CBS News was all over downtown Los Angeles, posting a video of journalists shielding themselves as police fired rubber bullets and other projectiles at protesters who had been blocking a gate. She captured the national guard arriving in L.A. and Rep. Jimmy Gomez being denied access to a detention center where he had intended to uphold his prerogative of conducting congressional oversight.

Tamara Mino with Univision 14 in the Bay Area covered protests against ICE on the street, but she also reported on her Instagram story that immigration courts were being closed and hearings in San Francisco and Concord canceled due to the protests.

León Krauze, an independent journalist and Washington Post op-ed writer who spent years at Univision, was reporting on the ground for Mexico’s El Universal in addition to providing analysis for the Post. On social media, he has urged fellow journalists to properly contextualize the story of the protests as being fueled by ICE operations and federal military escalation. Krauze said his advice for colleagues both in the United States and in Mexico, where coverage has been “intense and misguided in many ways,” is to always provide proper context.

“We’ve fallen into a narrative trap that benefits Trump’s rhetoric when we play the images of [burning] Waymo cars on a loop, when we insist there are riots in the city, instead of scattered and obviously reprehensible acts of looting and vandalism,” he told me. “When we ignore the true nature of the protests and who is protesting—that second- and third-generation Latinos are driving most of the peaceful protests downtown, many women, and young women who were incredibly courageous—I think you start to question how effective and trustworthy we are being.”

And then there was Paola Ramos, Jorge’s daughter and an MSNBC and Telemundo fixture. Though she was not in L.A., she wrote a widely shared Time essay that framed the conversation about the effects of the unrest in the city. She asked whether a country that overwhelmingly voted for mass deportations could ever feel a moral calling to defend immigrants again.

“This moment of empathy is not only the antidote to dehumanization, but also has the potential to upend the very story that got Trump elected to begin with,” she wrote. “After his victory and endless fearmongering, Trump counted on America to welcome his anti-immigrant agenda, underestimating Americans’ own capacity to feel compassion for immigrants. Perhaps, Americans also underestimated themselves. Until now.”

I HAVE NOT YET TRAVELED to Los Angeles. But as a Latino journalist, I’ve felt this moment hitting me in ways that remind me of intensely difficult moments from the recent past: the El Paso Walmart hate crime, the Uvalde school shooting, and, yes, the larger crusade against immigrants. Those stories are deeply personally affecting, and they remain so even as you compartmentalize the feelings in order to go out and do your job as a reporter.

But what Hispanic media has accomplished in its coverage of the protests in L.A. is not just providing a perspective that challenges the toxic information bubble of state propaganda excreted by Stephen Miller. Hispanic coverage of the protests has also provided the public with a larger, deeper understanding of what is happening—and what is to come. As Gov. Gavin Newsom warned, other cities will follow L.A. into unrest and uncertainty as Trump ramps up his deportation program. Already, there is news that Texas is mobilizing the national guard preemptively to get ahead of protests in San Antonio. That city has already been the site of essential Hispanic media reporting, including from Univision’s Lidia Terrazas, whose videos of families forced to deal with their mothers being taken from immigration courts have received millions of views on TikTok and Instagram.

Terrazas had noticed court detentions were happening in Phoenix and Miami, and on May 29, she went to San Antonio to investigate. While there, she witnessed Carmen Herrera, a mother of five daughters (all U.S. citizens), being detained by ICE agents. Herrera came to the United States at the age of 6 and has remained here for twenty-eight years. She had initially been relieved when she received her court summons because she has multiple pending cases to adjust her status, including one based on her marriage to a U.S. citizen, and a U-visa application for being the victim of a crime. Her detention left her family distraught, with one of her young daughters pleading for her return at a press conference.

Terrazas built a relationship with the family and was invited to their home, where that same daughter, Galilea, who recently lost her front baby teeth, spoke about the need for a mother to be in a household with so many girls. Her grandmother wept as she said Galilea told her she now sleeps with her mother’s clothing next to her, hugging it.

Terrazas herself once worked in the cherry fields of Yakima, Washington, when she had first arrived in the United States from Mexico. The journalist once feared her family could lose their legal status and sees importance in telling the story of Herrera, who cleaned homes during the week and painted houses on the weekend in order to support her family in America.

“We hear a lot of numbers when it comes to immigration arrests, or we hear how loud the changes are to immigration policy are, but a lot of times we don’t put a face to the story or the impact that change is making when so many families are going through the same situation—it is crazy,” she told me. “For me, it’s more than just [that] they’re arresting people at the courts, but what is the impact on the family of this woman being arrested?”

Correction (June 13, 2025, 11:00 a.m. EDT): As originally published this sentence referred to Ramos being in “semi-retirement” and the subheadline above referred to him being in “quasi-retirement”; they have both been reworded to reflect that Ramos had signaled when departing from Univision that he was not ending his career.

Thank you Adrian, as always, for all the important information that are providing to us. I hope that these Hispanic journalists are able to break through to the American people in a way that the legacy media has been unable to do. My ancestors came to this country last century for a better life and I have always loved this country for the opportunities that it has given me. It is beyond disturbing to me to see what ICE agents are doing, especially when they separate parents from their children. How do they face their own children when they go home at night?

Not afraid but pissed. My green-card holding wife turned that corner this morning and I was really proud. When we were arranging an annual trip to visit family in Indiana, she decided not to go because she didn't think she could face an airport. This morning she decided to bring the kids to the local Indivisible protest in Watsonville, CA. The silver lining awaiting us, I hope, is that the country might reach broad consensus after all this that we need/love/appreciate our immigrated neighbors and that the large number of undocumented is an administrative failure not a personal one. I might be getting ahead of events a little.