Portraits of the Minneapolis Resistance

Tens of thousands of Minnesotans hit the streets for a general strike on Friday. Here are a few of those fighting back against the ICE occupation.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

EVEN BEFORE THE KILLING OF Alex Jeffrey Pretti, 37, by Border Patrol officers on Saturday, Minneapolis’s social fabric was being torn apart. Over the course of several days in the city, I met activists, protesters, ‘ICE watch’ volunteers, and community leaders deeply angry and disillusioned about what was happening to their way of life. There was Carolina Ortiz, an immigrant advocate whom I tagged along with as she and others moved swiftly to respond to ICE sightings and organize help for those in danger. There were the thousands of people who hit the streets in -20 degree weather—yes negative—to protest the actions of ICE in their hometown. There were the local lawmakers forced to grapple with what happens when your own federal government is now targeting you, and the everyday citizens standing up for their neighbors and community in ways they never thought would be asked of them. Today’s newsletter is dedicated to telling their stories in an effort to underscore the myriad ways in which the Trump administration has harmed a great American city.

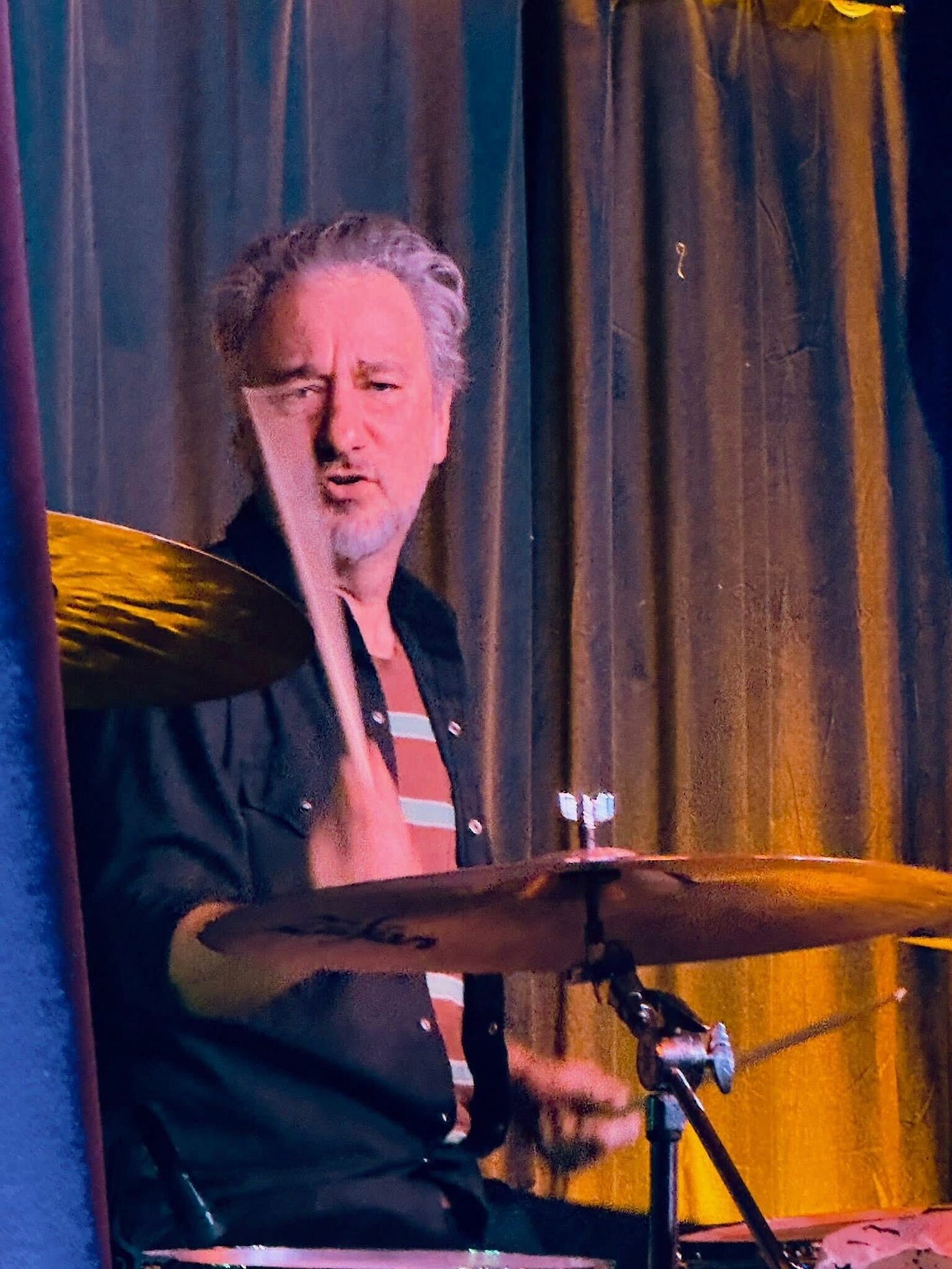

Noah Levy, 53, drummer

The day before Renee Nicole Good was shot and killed by an ICE agent, Noah Levy was also watching ICE agents as an observer. He told me that he and his wife were following the agents around town, and in turn ICE went to his house and used his wife’s first name. The message was clear: they’re watching him.

Because of ICE’s aggressive tactics and unrelenting harassment of the citizens of Minneapolis, Levy took part in “ICE out of Minnesota: Day of Truth and Freedom,” a protest on Friday that involved a blackout on all work, school, and shopping. He connected with 35 other drummers to put on a raucous publicity stunt on the Stone Arch Bridge in downtown Minneapolis. His goal was to draw eyes to the work important advocacy groups like COPAL are doing to help the community.

“All of us musicians in town are looking at each other like, what can we do? We can throw together shows but people are stuck in their homes, they need rides. We’ve heard horror stories of people who need medical care because ICE is coming to hospitals so they’re not getting help. Well, we can do something visually arresting, but we also want to scream out into the void on the coldest day in 10 years.”

So why the hell did he put his bodily safety (the high was around -9 degrees on Friday) on the line after ICE killed a white observer just like him?

“I’m still involved because I care about my neighbors,” he told me. “I was just talking to my friend who is moving back here because of the sense of community. This is why they’re cracking down on our cities, because of what we stand for. St Paul, Minneapolis—if we didn’t have that, we wouldn’t exist. We’re all looking each other in the eyes. It’s personal, it’s deeply personal.”

Segundo Balboa, 44, co-owner of Galapagos Bar & Grill

Segundo Balboa is a U.S. citizen who came from Ecuador twenty-five years ago. Being half-Ecuadorian myself, I know that Ecuadorians can be overly formal with strangers or authority figures. But when we discussed Renee Nicole Good, he used her first name. It wasn’t out of disrespect; in fact, I found the tender way he called her “Renee” to come from a deep sense of affection for her and of sadness over her tragic killing.

Balboa began by explaining to me that he saw federal agents enter the Twin Cities in significant numbers in early December, which is when the trouble for the Latino community began.

“The Christmas season was not a celebratory Christmas season,” he said. “There were no days of holiday for Latinos.” He said he has lost 90 percent of his business, the chill from ICE agents keeping his customer base far away. But still he keeps his restaurant open, if for no one else than his two children and younger baby.

Good’s killing has changed the way he views his safety as a U.S. citizen.

“You think twice about leaving work,” he confessed. “They’re taking away freedom of speech to protest nonviolently. Now if we protest and oppose the policies of Trump, we’re terrorists.”

Irma Márquez Trapero, 35, head of LatinoLEAD

Irma Márquez Trapero was awake at 4 a.m. having received a tip that a meatpacking plant where her mom works could be an ICE target. After a few frantic outgoing calls, she found out her mother was already planning to stay home. Such is the urgency of people doing the work to protect immigrants, including their own families.

Trapero runs LatinoLEAD, a cross-sector hub of 3,000 people that uses chat apps like Signal and WhatsApp to connect people across government, the non-profit sector, and advocacy groups. But having grown up in rural Minnesota, Márquez Trapero felt she had a unique view of the full scope of ICE’s invasion into Minnesota. She used a Latino roundtable led by the office of Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz this week to warn of a coming danger in the state and the need to create support plans and share available resources outside of just the Twin Cities.

“The majority of Latinos live in greater Minnesota and in rural areas,” she told me, “and I’m sounding the alarm because greater Minnesota is going to be targeted, an area where the community is most vulnerable and has less resources available.”

Daniel Hernandez, 41, owner of Colonial Market and Restaurant

Daniel Hernandez has been in Minnesota a quarter century and is a DACA recipient. By his observation, ICE’s actions in the Twin Cities over the past two months look more like a military occupation than a law-enforcement action.

“The way they’re moving, every single aspect is literally a military campaign inside the country,” he told me.

He saw the danger early and began preparing before things got bad late last year. As the owner of a supermarket chain, he thought of his employees and their families. He has been spearheading efforts to help ensure vulnerable migrants fill out and file Delegation of Parental Authority (DOPA) forms; if an immigrant is taken by ICE, the DOPA authorizes specific family members or friends to take care of and make decisions for their child in their absence. In just the past year, he has helped the parents of 2,575 kids find some solace and peace of mind with the DOPA paperwork.

Hernandez is a force of nature. When I arrived at his supermarket, he was there with just one other employee. Hernandez was on the phone with a New York Times reporter. He told them what he told me: that he offers free grocery delivery—which isn’t free for him, of course. But he also told me something earlier that he didn’t tell the Times then: He also gives food away for free if people come to him in need.

“People who do not have money, we have ways to give them free food, but I don’t advertise it, I still need to sell. But I usually bring them $150 worth of food,” he told me.

The remarkable generosity is even more staggering when you realize how much Trump’s presidency and the current ICE occupation is costing Hernandez.

“I used to sell $1 million per month,” he says of the period before Trump took office. “Right now we’re selling $175,000 per month. I’m going to stay open as long as I can. The owner of the building decided to waive my rent for three months. Without the income I should be getting, I haven’t paid myself.”

Hernandez couldn’t protect everyone from the effects of ICE occupation, as he’s had to let employees go. His supermarket once had seventy employees; now it has just eighteen.

Still, he moves forward. He’s currently trying to raise $1 million to create the “biggest fundraiser in Minnesota history for Latinos.” He already has a $100,000 pledge to jumpstart his effort. Hernandez said he wants it to be run by churches and non-profits, but for the money to be able to be spent at smaller Latino-owned grocery stores instead of big box stores like Walmart or Target.

As I prepare to leave, I meet Dean, a white 69-year-old retired physician, who stood out as one of the only non-Latino people there. He was returning from delivering groceries to Latino families and was about to pick up more for another delivery. He had met Hernandez at church, and when he and his wife heard his call for people to deliver groceries, he asked himself, “Why not?”

“It’s just sad,” Dean told me, noting that when he arrives at Latino homes, they cautiously peek through the blinds, wary of who might be at the door.

Before I’m done, I turn to Hernandez, who has DACA status and could have his life made very difficult by these overzealous and under-qualified ICE agents rampaging his community, and I ask him if he’s worried he might be next.

He invokes the twentieth-century Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata.

“‘I’d rather die on my feet than live on my knees,’” he says, quoting Zapata. “If they want to get me they can get me here, outside, or at home like they have to so many others.”

To hear more, check out Adrian’s discussion of this story with Bulwark Managing Editor Sam Stein:

Do you have a link for the Hernandez fundraiser or other relevant fundraisers?

Adrian, Thanks for bringing us these profiles in courage. This willingness to help your fellow man is the heart of humanity. The character of these individuals is astounding. This is what dignity looks like. Everyday I am more and more ashamed of this country of ours, that we even have one citizen in this country that is OK with this ICE lawless invasion is sickening. The fact that we have the people in charge of our country executing this horror is unconscionable. Hopefully, we can find many more people with such courage as you reported to oppose and halt this evil plan.