The Algorithmic Prison

There’s a moment in Oliver Stone’s JFK very early on, after the initial news of the shooting breaks, where Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) has retired to a bar to watch news roll in over the TV. After Kennedy’s death is confirmed by Walter Cronkite, who sheds his famous tear, a voice rings out in the bar, accompanied by boisterous claps. “He’s dirty. Goodbye, you sorry bastard,” a man yells. The barfly reveling in Kennedy’s death, importantly, is alone. Most of the people are quiet, in shock, saddened by the news. “Shut the fuck up!” another patron yells in response.

I think about this moment1 a lot, particularly about how social media has made that lone guy in the bar louder than he would otherwise be. Taken in isolation, the guy who celebrates the death of a fellow citizen, even a divisive citizen, is generally the outlier; most people have enough tact to at least stay quiet in the immediate aftermath of a murder. But the internet, and especially social media, will take that guy, that one out of every hundred, and connect him with the rest of the 1 percent he represents. Then, thanks to the algorithmic propensity to feed people content they’ll hate—because hate drives angry responses and responses mean more content and more content means more advertising and more advertising means more cash—that guy becomes THE guy, he becomes representative, he shows people how to get likes and retweets and attention.

And so it was this week, after the murder of Charlie Kirk. On both Twitter and Bluesky, my “following” feed—that is, the posts from people I have made community with—were, by and large, despondent. At the very least, they were rarely gleeful. When I switched over to the algorithmic feeds, the “for you” and “discover” feeds, the story was very different: delighted merriment and callous disregard were the order of the day.

This is all the more horrifying because of the footage of Kirk being shot that we had almost immediately afterward. I will neither link to it nor describe it; suffice to say, it was yet another instance of a snuff film going viral on social media hot on the heels of the snuff film of the Ukrainian woman stabbed to death on a Charlotte bus. I’ve written about this before, after the cold-blooded killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, but I am genuinely horrified by social media’s amplification of these clips, of the incentives offered in particular by X and Elon Musk’s monetization schemes to propagate such films, and of the wickedly gleeful responses they encourage in others who find community in the suffering of their perceived enemies.

At the end of last year, I went JVL-dark in our Bulwark 2025 prognostications video and predicted a wave of social violence unlike any we’ve seen since the late 1960s or early 1970s. There are a few reasons I had in mind for why that might come back into vogue. One is the desire of accelerationists on both sides to speed us toward societal disaster. But looming even larger is the potential of virality, the knowledge that any such murder will become an instant social media sensation, the copycat urge manifesting itself over and over again as we see that the man in the bar cheering JFK’s assassination isn’t all alone, can’t be properly ostracized by any rational community. Bad times are coming.

Hell. They’re here already.

The Long Walk review

There are two competing responses to The Long Walk rattling around in my head as I sit down to write about it.

Speaking as a critic, Francis Lawrence’s film is something of a miracle: For a movie that is, largely, sequences of young men walking on a street and talking to each other, it is entirely riveting. Harrowing, even, because of what happens when they stop walking: They get shot. Last man walkin’ wins unimaginable wealth and the fulfillment of one wish by the tattered remains of the American government.

Lawrence, directing a script written by JT Mollner adapted from a novella by Richard Bachman, has done something that shouldn’t work at all, yet mostly does: He has combined the tough-time hangout male camaraderie of a movie like The Shawshank Redemption with an utterly grisly horror movie that rarely flinches from seeing young men get their faces and bodies ripped apart by automatic weaponry. This is punctuated by the film’s opening moments, when the first of the “contestants” to fall does so after only a few short miles, succumbing to cramps that bring his speed under the required three miles per hour. Three warnings and BAM, a bullet rips off half his face, prompting the appearance of the film’s title card, the brutality and the banality emphasizing the sadistic nature of the enterprise these kids have signed up for.

Fifty young men, one from each state, have joined for this annual Hunger Games–style low-speed ultramarathon designed to lift the spirits of a weary nation. As Raymond Garraty (Cooper Hoffman) notes, the Long Walk isn’t compulsory, precisely, but no one they know fails to submit for the lottery. The prize is too great, the hope all they have in this civil war-torn landscape. Garraty quickly bonds with Peter McVries (David Jonsson) and a handful of the other walkers; they find an antagonist in the sociopathic Barkovitch (Charlie Plummer). That most of the boys we’re watching will die is a fait accompli, the only question is how and when and at whose hand.

Again, none of this should really work, and the moments it works the least are the hammier scenes dominated by the Major (Mark Hamill), who barks encouragement at them in khaki fatigues from behind commandant shades, a parody of a Central American caudillo transplanted to the Midwest. In a movie filled with supple, heartbreaking performances—primarily from Hoffman and Jonsson, though Tut Nyuot, Ben Wang, and Joshua Odjick also do gutwrenching work here—Hamill’s bluntness is jarring. It is, undoubtedly, an intentional choice by Lawrence and Hamill; I just don’t think it quite works.

Lawrence keeps The Long Walk moving at the same relentless pace of its characters and we feel every cramp, every retch, every bullet. That their agony is created for the amusement of onlookers at home is, ultimately, the final indignity each of these boys face.

Which brings me to my second response, sitting in that theater on Thursday night. Because we like to think we’re not the same as the Major’s bloodthirsty audience; we like to think we’re watching these boys get their faces blown off not out of titillation but because it is our somber duty to view the violence, to witness their sacrifice, to wallow in the nihilistic senselessness of it all. We watch this to condemn it, not to celebrate it. We put ourselves above the Major’s cheering masses, the rubes who gather to listen to “America the Beautiful” as fireworks go off and a new champion is crowned atop the mass grave of his fellow walkers.

But … I don’t know, guys. I don’t know. I see how we respond to the violence we’re fed via social media. I see the glee, barely restrained or otherwise, that comes with witnessing the violent end of a man who said things we hate. I see the wishful hopes for vengeance on his behalf, the petty cancelation campaigns launched in retaliation, the fervent desire for more ruined lives. I see the natural desire for the crushing of enemies and the lamentations of their women. I see the barbarian in all of us; I see it all around us.

And then I look around at the people who paid $20 to watch kids come together in brotherhood only to get shot in the face on a Thursday night and yes, it’s just a movie, and yes, the shooting is bad, we all agree the shooting is bad, we all agree that what we’re watching is cruel and evil, but we are not cruel or evil, and the cathartic conclusion to the film is not cruel or evil. It’s some other guy that’s cruel and evil. Over there. He’s the real problem. If we can just get rid of that guy, we’ll be fine.

I see all this. I see everything. And it fills me with despair.

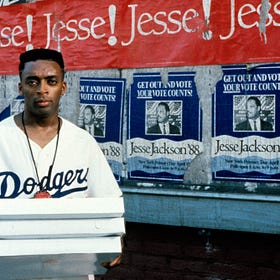

On Across the Movie Aisle, we discussed Highest 2 Lowest, Spike Lee and Denzel Washington’s latest collaboration. It’s good! It’s a cranky old man movie and I’m a cranky old man. I loved it!

The Delightfully Cranky 'Highest 2 Lowest'

On this week’s episode, Sonny, Alyssa, and Peter asked why Activision would turn down a chance to have Steven Spielberg direct a Call of Duty movie. Then they reviewed Highest 2 Lowest, the latest collaboration between Spike Lee and Denzel Washington. Spoiler: We all loved the score, which is apparently a controversial …

And we had a Spike Lee draft in the bonus episode! Some fun picks here.

Spike Lee Draft!

On Monday, Peter, Alyssa and I taped a Spike Lee draft. It’s a fun episode, I hope you enjoy, and hopefully it makes your day a little brighter.

Assigned viewing: Clear and Present Danger (Kanopy, Pluto)

For the Bulwark Movie Club (which is taking a week off, after a bunch of stuff got shuffled around this week), we’ll be discussing Phillip Noyce’s second Jack Ryan film, Clear and Present Danger. I’m just going to put this out there: It’s probably my favorite Jack Ryan movie. Not necessarily the best—Hunt for Red October is a better, more cohesive film—but it’s definitely the one I find myself most regularly wanting to revisit.

I actually think about this movie a lot, to be honest—it is as precise an examination of the conspiratorial mindset that has come to dominate American political thinking as has ever been made—but that’s a post for another day.

I think we can call it - social media was a mistake. Well, algorithmic social media is a mistake. Mass media always dehumanized people, which is fine when it is fictional characters. Then it morphed into making sport of public figures, Paul Reubens come to mind. Then we took “real people” and made them into “celebrity stars.” Now social media turns everybody into targets of ridicule. A person’s worst day goes “viral.” We lose sight of people’s humanity and then lose ours in the process.

It’s all like a Stephen King novella.

We’ve all been fortunate enough to grow up in the most prosperous country the world has ever seen during the most peaceful 75 years of human history. Ethnic cleansing, massacres, famine - those things still happened, but without the same frequency. They certainly didn’t happen here. Couldn’t happen here.

No more. Movies like the Long Walk confront that. Or at least that seems to be their intention. I don’t need that. I’d feel the same way as credits rolled.