Greenland’s Persistent Predator

Trump keeps threatening, no matter how many times his victims ask him to stop.

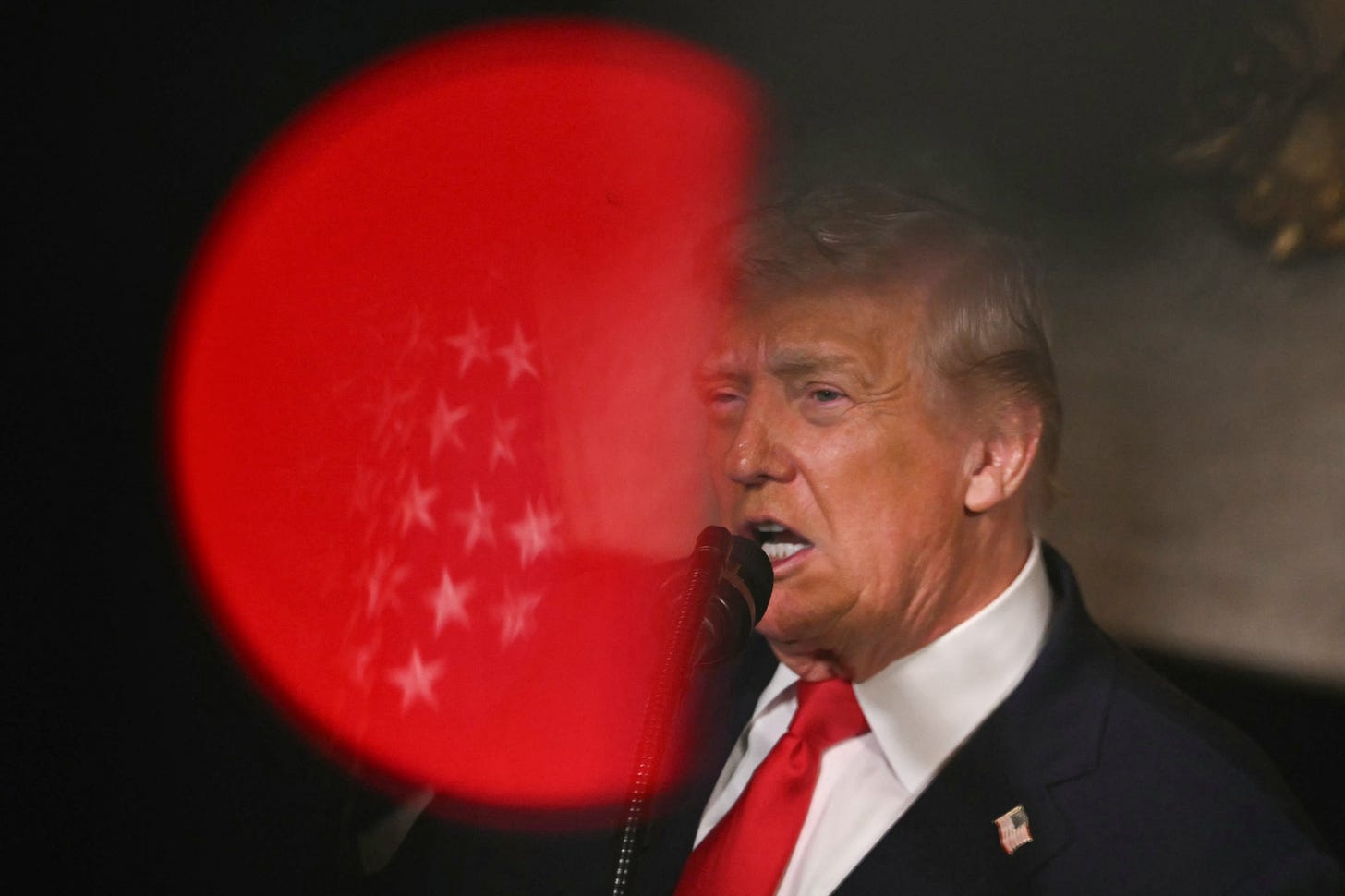

IN THE YEAR SINCE DONALD TRUMP returned to power, the United States has become—as one of Trump’s supporters, Rep. Andy Ogles of Tennessee, admiringly put it on Wednesday—“the dominant predator” in the Western Hemisphere. Trump has extorted Canada and Ukraine, threatened Panama and Colombia, invaded Venezuela, and deployed the American military to loot Venezuela’s oil.

Now Trump is circling back to a familiar target: Greenland. He doesn’t care that the island territory and its parent country, Denmark, have done nothing to deserve aggression. Nor does he care that they’re part of NATO. And he’s utterly indifferent—just as he’s always been with his abuse of women—to their requests to be left alone. He keeps threatening and harassing Greenland and Denmark, no matter how many times they ask him to stop.

The cycle of rejection and harassment goes back to 2019, when Trump first floated the idea of buying Greenland in “a large real estate deal.” Denmark’s new prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, brushed it off as “absurd.” “Greenland is not Danish. Greenland belongs to Greenland,” she told the press. She noted that Greenland’s prime minister had “made it clear that Greenland is not for sale.”

Trump responded by punishing Denmark. He canceled a state visit to the country and huffed, “You don’t talk to the United States that way, at least under me.” (It’s in interactions with women, both personally and politically, that Trump’s boorishness comes to the fore.)

In the years after that tiff, Trump focused on other targets, such as the U.S. Capitol. But a year ago, just before starting his second term, he began to apply pressure. On January 7, 2025, he warned Denmark that if it blocked him from acquiring Greenland, “I would tariff Denmark at a very high level.” Two days later, he renewed that threat.

Again, Denmark and Greenland said no. On January 10, Greenland’s prime minister explained, “Greenland is for the Greenlandic people. We do not want to be Danish, we do not want to be American.” On January 15, Frederiksen told Trump that she was happy to advance American interests in Greenland but that the island belonged to its people and wasn’t for sale. On January 28, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, without naming Trump, reminded him, “The inviolability of borders is a fundamental principle of international law.”

Trump and JD Vance blew off these objections. On February 2, Vance scoffed that Trump “doesn’t care about what the Europeans scream at us.” Trump, in his State of the Union address on March 4, went after Greenland again, vowing, “One way or the other, we’re going to get it.” On March 29, Trump said there was a “good possibility that we could do it [take Greenland] without military force,” but he added, “I don’t take anything off the table.” On May 2, he stipulated again that force was an option.

For the rest of the year, Trump was busy with Iran, Gaza, Ukraine, and other war zones. But on Saturday, after he struck Venezuela, Katie Miller—his former deputy press secretary and the wife of his deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller—posted a tweet suggesting that America should claim Greenland next. This prompted a statement from Greenland’s prime minister: “No more pressure. No more hints. No more fantasies about annexation.” That was followed by another statement from Frederiksen, imploring the United States to “stop the threats” against Greenland and Denmark. “The USA has no right to annex” Greenland, she insisted.

Trump ignored the rebuffs. Six hours after the statement from Greenland and four hours after the plea from Frederiksen, he demanded the island again: “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security. And Denmark is not going to be able to do it.”

That was Sunday. On Monday, Frederiksen tried again. In an interview with Danish TV, she decried Trump’s “unacceptable pressure”—still without using his name—and warned that “if the United States were to choose to attack another NATO country,” NATO and the global order “would collapse.”

The tension was escalating, but the Trump administration refused to back off. Seven hours after Frederiksen’s interview, CNN’s Jake Tapper read her remarks to Stephen Miller on the air. He asked Miller, “Can you rule out that the U.S. is ever going to try to take Greenland by force?” Miller didn’t budge. He repeated Trump’s position: “The United States should have Greenland as part of the United States.” And he assured Tapper there would be no war—not because Trump would hold back, but because nobody would try to stop him. Greenland’s population was paltry, said Miller. “Nobody’s going to fight the United States militarily over the future of Greenland.”

On Tuesday, the leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland, and the United Kingdom joined Frederiksen in another attempt to deter Trump. “The Kingdom of Denmark—including Greenland—is part of NATO,” they reminded Trump. They asked the United States to respect “sovereignty, territorial integrity and the inviolability of borders. These are universal principles, and we will not stop defending them.”

Their words made no difference. Two hours after that statement, Trump’s envoy to Greenland, Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry, dismissed it. On CNBC, Landry called for pursuing Greenland “without Europe” getting in the way. And later that day, the White House put out a defiant retort to the Europeans. “President Trump has made it well known that acquiring Greenland is a national security priority of the United States,” said the statement from White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt. “The President and his team are discussing a range of options,” it continued, and “utilizing the U.S. Military is always an option at the Commander in Chief’s disposal.”

Denmark and Greenland, alarmed by this bellicosity, requested a meeting with Secretary of State Marco Rubio. But on Wednesday, when he was asked about Greenland, Rubio reaffirmed that “every president always retains the option” of military force. Rubio claimed he wasn’t referring specifically to Greenland, but then he cited Venezuela as an example of what could happen to countries that didn’t heed Trump’s threats. Leavitt made the same point when she was asked about Greenland at Wednesday’s White House briefing. “All options are always on the table,” including force, she repeated, naming Venezuela and Iran as countries that had failed to meet Trump’s demands.

When you look at the history of this persistent harassment—the episode in 2019, the threats last year, and the resumption of hostile behavior since the attack on Venezuela—the pattern is clear. Greenland, Denmark, and Europe keep saying no, but Trump and his lieutenants refuse to listen. Now that the Trump regime has hit Iran and Venezuela, it’s hinting that Denmark, like Cuba and Colombia, had better wise up—or else. The predation will go on until somebody stops the predator.

Take his trump llc properties in Europe. Bullies pick on who they think are too weak to resist.

The language in the piece keeps reminding me of the Epstein files. “Dominant predator,” “persistent harassment.” It all fits a pattern. And now that his mind is going, it will be worse.

The same cannot be said for those around him who are propping up this aging, raging authoritarian. They know better. Destroying NATO would be unforgivable, and people like Vance and Rubio, who ARE in their right minds, will have some very hard questions to answer once the actuarial tables kick in and this horrible timeline is finally over.