Thirty Years Later, ‘Xena: Warrior Princess’ Still Rides On

The iconic Lucy Lawless–led fantasy show still has legions of loyal fans.

THIRTY YEARS AGO, on September 4, 1995, a new kind of hero rode onto American television screens. She appeared out of the mist, a warrior haunted by dark memories that came flashing back as she rode through a devastated village. Resolved to put her violent past behind her, she buried her weapons and armor—and then was promptly called back to action when she saw a band of thugs terrorizing a group of innocent captives. She fought these brigands, wearing only her shift, using her fists and boots and then her recovered weapons, grinning with glee as she brought down her opponents. By the end of the episode, she had faced an angry crowd in her own village where people viewed her as a dangerous criminal, then earned the same people’s gratitude by fighting and defeating a warlord to save them, and acquired a friend and traveling companion—an idealistic village girl seeking a better life.

She was Xena, Warrior Princess—the titular character of a show that would run for six years and 134 episodes, become a cult hit, and galvanize an international fandom. The voiceover for the credits ended with, “Her courage will change the world.” That was certainly true for Xena in her fictional universe loosely based on ancient Greece and Rome with detours into the Middle East, North Africa, China, the British Isles, and more. In the real world, plenty of people felt that Xena: Warrior Princess had changed their lives. It also had a transformative impact on popular culture.

Xena, played by New Zealand actress Lucy Lawless, had made her first appearance in a three-episode arc on another show, Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, that ran several months before the Xena premiere. She was a “warrior princess”—apparently, the female equivalent of “warlord”—who set out, and failed, to kill Hercules, then clashed with her own army after saving a baby during a raid on a village, and joined Hercules as his ally and lover before going off on her own quest to redeem herself. While this early Hercules version of the character was unevenly written—Xena was more of a temptress with serious fighting skills in the first episode, a dark but basically honorable warrior in the second—the studio was sufficiently impressed to greenlight a spinoff. Before long, the spinoff had overshadowed the parent show, much to the frustration of Hercules star Kevin Sorbo.

Hercules was a fun, campy adventure show that appealed to both kids and adults, very much a product of the glory days of syndicated television—as was Xena. But because of the heroine’s villainous past (in which, she acquired the moniker “Destroyer of Nations”), and her burden of guilt and inner conflicts, Xena was darker and more complex from the beginning—and got more so as the show went on. Where Hercules never killed even the worst of evildoers, Xena and her friend and sidekick Gabrielle sometimes had to grapple with the knowledge that their actions had cost innocent lives. In a striking example of Xena’s fifty shades of moral gray, one of her main recurring foes, the female warrior Callisto (Hudson Leick), was a ruthless killer whose vendetta against Xena gave her a very real claim to sympathy: Back in the day, Callisto’s parents and sister had died in a devastating fire that began when Xena and her army raided their village.

Xena also stood out as a female-centered action/adventure show with a unique heroine. She had no male support system and no magical or supernatural powers. (Some early ideas about giving her a divine origin were rejected in part to avoid any suggestion that it was the reason for her formidable prowess as a warrior.) She had the classic traits of the male hero—fierce and fearless, stoic, self-sufficient, straightforward, brashly confident in her strength and skill—but was also gloriously and unapologetically female. “There’s nothing like it on television,” Lawless said in an early promo—and she was right.

Xena could get dirty and sweaty in a fight; she could also change from her armor into a simple dress (and look stunning), then slash the sides of the skirt so that it wouldn’t get in the way and deliver a memorable ass-kicking to the baddies du jour. In the second season premiere, “Orphan of War,” she spoke poignantly of her enduring bond to the child she had given away at birth to give him a chance at a peaceful life: “A lot of people think that giving birth ends when the baby takes its first free breath. It’s not true. My son has grown inside of me every day, stronger and stronger.” Later on, in a storyline that arose from Lawless’s real-life pregnancy during the fifth season, Xena had another baby—onscreen—and became the world’s first action hero who had to take a break from breastfeeding to fend off attackers, with a ready quip: “Every time you sit down to eat. . .”

Besides Xena herself, Xena: Warrior Princess boasted a remarkable gallery of female characters—heroes, villains, or both. Gabrielle (Renée O’Connor) pursued her own hero’s journey, growing from a naïve young girl who dreamed of being a warrior and a poet to a fighter who was Xena’s near-equal (but at a tragic price). There was the Chinese sage and Xena’s onetime mentor Lao Ma (Jacqueline Kim), revealed as the real author of the Taoist texts attributed to Lao Tzu (who may be mythical as well, so why not?). There was Najara (Kathryn Morris), a warrior and religious leader whose fight for good turned out to have a darker side of cultlike zealotry. There were Amazon warriors and queens whose tribes were not idealized female utopias but societies with their own power struggles, conflicts, and flawed leaders. But female-driven as it was, the show also featured a rich range of male characters, notably Ares (Kevin Smith), who evolved from a charismatic adversary seeking to lure Xena back to the dark side into a complex “frenemy” and love interest with his own potential for redemption; Joxer (Ted Raimi), a bumbling wannabe warrior whose comic-relief ineptitude masked what Xena once called “the heart of a lion”; and, in the flashbacks, Xena’s onetime lover and fellow warlord Borias (Marton Csokas), who first showed her the path out of darkness by questioning their pursuit of power and riches and risking everything for their child’s future.

Was it a feminist show? Yes, in the best sense of having women at its center and showing them to be as fully human as men: heroic and flawed, strong and weak, capable of good and bad. But it never made good and bad an issue of gender, and it never had a heavy-handed message of female empowerment. Xena and Gabrielle did not fight the patriarchy so much as they ignored it—which, granted, was made much easier by the way the show wrote it out of existence, a creative decision very much in the “postfeminist” spirit of the 1990s. As guest star Jennifer Sky, who played the young Amazon Amarice in the fourth and fifth seasons, succinctly put it in a 2013 tribute: “Gender was not relevant in the Xenaverse. There, a girl or a boy could be a warlord or a farmer, a bard or a sad sack needing protection.” In this fantasy version of the ancient world, the Warrior Princess could step up and take command of an army, or take charge of the defense of a city under siege, without anyone questioning a woman’s ability to lead. This is not so much historically inaccurate as simply unconcerned with historical reality: Accuracy was never going to be a primary goal for a show whose heroine could meet King David, Sophocles, and Cleopatra (and have Julius Caesar, played by Star Trek’s Karl Urban, as her former lover and current archenemy).

“I was shocked when Ms. magazine came out saying [Xena] was a feminist icon,” Lawless told me in a recent interview over Zoom, “because feminism to me was something that belonged to a bygone era.” Partly, she says, she now sees that attitude as stemming from ignorance—a failure to realize to what extent she was a beneficiary of earlier generations of feminists in New Zealand, the first nation to grant all women the right to vote, way back in 1893. But the idea that gender is no obstacle is something Lawless still sees as formative to her life. “My parents expected as much out of me as out of my brothers, that you could do anything you wanted,” she told me—and maybe that’s one reason she was such a perfect lead for a show built around the same idea.

IF THE SHOW HAD A MESSAGE of empowerment, it was, above all, about redemption: As Lawless sums it up, “Yes, you’re imperfect, but you deserve to have love . . . you have value.” That, she thinks, is one of the reasons the show developed such a passionate fandom that drew many people who grew up struggling with personal issues or dealing with shame—including many people who “felt marginalized.” Lesbian fans who thought they saw a budding romance between Xena and Gabrielle, two women who traveled together and were intensely devoted to each other, were undoubtedly the best-known fandom demographic; but Lawless points out that there were many others, including African-American women.

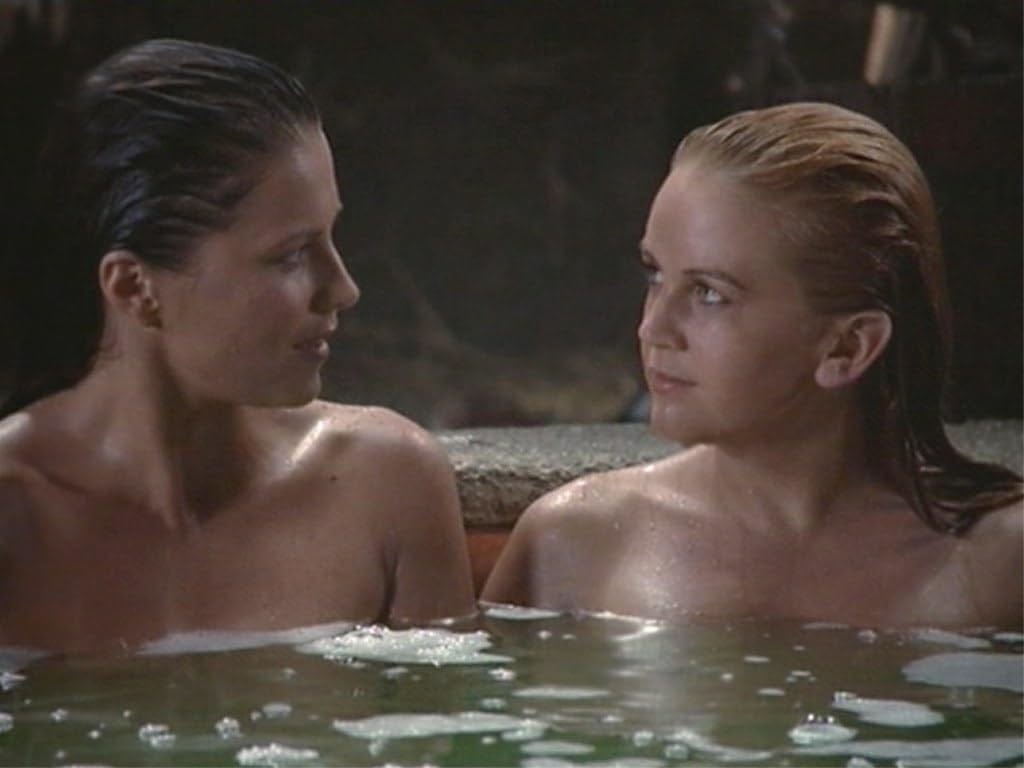

In those early days of the internet, Xena had a busy online life in chat rooms, forums, and fan sites that hosted everything from fanfiction to quasi-scholarly essays (“The Myth of the Redeemer in Xena: Warrior Princess,” for example), as well as bustling conventions. The fandom was a place where many people found excitement, friendship, and creativity. But it could also be contentious, especially as the show began to play to, and with, the lesbian subtext, sometimes turning it into an “are they or aren’t they” game. Yet the show also unabashedly leaned into the smoldering sexual tension and complicated feelings between Xena and Ares, an ongoing dynamic that excited many in the fandom, and on a few occasions brought in a transient male romantic interest (such as Marc Antony—you know, the one from “and Cleopatra”). Inevitable online fighting ensued. Fans could get quite “proprietary,” says Lawless: “I learned early on not to be poking around in chat forums.”

In an interview in 2003, two years after the Xena finale, Lawless recalled that fandom ugliness toward the end of the show took a heavy toll on her, particularly since much of it was directed at her husband Robert Tapert—who was also Xena’s executive producer. “I felt like there were a few people out there . . . that were so malevolent and so malicious they clouded everything else,” she told the New Zealand magazine Metro. Things probably got even nastier after the series finale in which Xena sacrificed her life on an adventure in Japan to atone for yet another past wrong and Gabrielle sailed back to Greece alone; for once, the anger on the forums may have united all the fandom factions.

But that was almost twenty-five years ago. The Xena fans who are still active today, Lawless told me, are “wonderful people,” some of whom have been there from the beginning and some of whom are new. Meanwhile, says Lawless, “the trolls have dropped away, and they’ve gone on to, I don’t know, watch reality television or something.”

The “were they or weren’t they” question still comes up, along with claims that it has been definitively resolved. In retrospect, the answer from Lawless is that the answer shouldn’t be important: “If they reboot Xena, if they were to make her gay and she and Gabrielle kissed every week—so what? It’s still not [the essence of] the show, just as it doesn’t matter if the fireman who is putting out your house is gay. It’s still about some kind of inner journey—your sexuality doesn’t matter.”

And indeed, for legions of fans, Xena is still, first and foremost, a warrior on a quest. “What I love most is how Xena blends strength, humor, and heart. She’s fierce, flawed, and a fantastically human warrior woman—and I see myself in that warrior spirit,” Tracie Sillers, a finance manager and still-active fan in Sydney, Australia, wrote to me in an email. The warrior spirit and the fight for the “greater good” can manifest themselves in many ways in the real world of today. For Sillers, it is reflected in the challenges of being the mother of a child with disabilities.

Sillers’s personal story reflects those of many fans who are keeping the flame alive. She first got hooked on the show as a young adult in the 1990s—it was, she says, the only show she and her brother agreed on. When she started watching the reruns more than a decade later, “the warrior flame roared back to life.” This time, Sillers not only joined the online fandom, where she found “some amazing lifelong friends,” but started going to conventions and even cosplaying as Xena.

Some old-time fans who still love the show are now bringing their kids into the “Xenite” fold—and, apparently, kids today can still love Xena even without state-of the-art special effects. (In our interview, Lawless felt compelled to laughingly apologize for a scene in one early episode, featuring an extremely fake giant bird and massive green eggs that . . . oh, never mind.) The practical effects and stunts have their own charm: “I really like Xena because of all its interesting themes, and also the authenticity of it and how there’s not much CGI, which means the fire breathing is real and the house burning is real,” a friend’s 11-year-old daughter, who has been watching the series with her mother and older brother, wrote to me when she found out I was writing about the Xena anniversary. “And yeah, it’s my favorite TV show.”

Clearly, Xena lives on.

XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS was an action-heavy show, with often brilliantly choreographed fight sequences influenced by Hong Kong action movies; Lawless and O’Connor performed many of their own stunts.1 But it was also much more than that. Xena had some memorable dialogue that combined drama with biting wit, as when Callisto, making her series debut, told Xena, “As a villain, you were awesome. As a hero, you are a sentimental fool.” Storylines drew from mythology, history, literature, and film—everything from the Greek Orestes mythos to the Caesar/Pompey rivalry in the late Roman republic to It’s a Wonderful Life and The Producers.2 It went to such creative places as a musical episode set in a magical world with sets and costumes based on Tarot cards. And it managed to explore deep and complex themes—such as the ever-relevant question of how to retain one’s humanity in a war in which, in Xena’s words, “there are no good choices, only lesser degrees of evil”3—without taking itself too seriously. The intense drama nearly always came with quirky humor—and, often, a healthy dollop of cheese.4

There were also gorgeous visuals that more than made up for those hokey special effects: the lush New Zealand landscapes doubling as ancient Greece, Britain, or China,5 the stunning costumes by subsequent Oscar winner Ngila Dickson. There was the rich music by Joe LoDuca, which won an Emmy in 2000 and earned six other nominations. But above all, the show’s power was owed to the actors and the emotion they could bring to the screen. Lawless was not only charismatic, sexy, and—despite a dislike for fight scenes—credible as a physically powerful woman; she also had a remarkable ability to inhabit the character’s skin. And not just one character: Aside from comical storylines featuring three Xena lookalikes and an episode set in the 1940s in which Lawless played a nerdy, prim Xena descendant, a remarkable Season 2 episode had a Xena/Callisto body switch, impressively acted by both Lawless and Leick.

Never, perhaps, has Xena been done a greater injustice than when an early New York Times article on its runaway success described the heroine as having “only two basic expressions: a contemptuous sneer for the men foolish enough to challenge her, and a hard, resolute stare.” One can only wonder how much of the show the writer had seen. Yes, the sneers and stares were there, but so were the smiles, the tender looks, the moments of poignant vulnerability. One could look to Xena’s scenes with her son who has no idea that she is his mother, or to “One Against an Army”—a fan favorite in which Xena tries to stop the Persian army’s invasion of Greece while trapped in a cabin with a desperately ill Gabrielle—for episodes in which we see both the fury and the gentleness. Hers was “a face that every emotion was just pouring out of,” former Xena Fan Club president Sharon Delaney told me in a Zoom interview. It’s an apt description. (Delaney says she first started watching the show only because of her job with Creation Entertainment, which got the Xena licensing rights soon after the show started, but got hooked after the first two episodes she watched brought her to tears.)

Lawless also had a rare chemistry with O’Connor, who was a natural at playing Gabrielle’s fresh-faced, childlike innocence, and bubbly enthusiasm early on, but also effectively conveyed her later evolution. Among the supporting cast, one may particularly single out Leick—a funny, terrifying, and sometimes sympathetic Callisto—as a fine performer who left acting post-Xena, and Smith, a remarkably versatile actor who gave the God of War both humor and a surprising humanity (and who tragically died in an accident on a film set in China some six months after the show ended).

Even the most devoted Xena fans will inevitably, and sometimes harshly, criticize some aspects of the show. While the first three seasons are considered the “classic” period (Season 3 in particular is often seen as its golden age), the last three were far more divisive. There were storylines that took the show in new directions and were loved by some viewers and hated by others: an India arc with mystical gurus and reincarnation motifs that ended with Gabrielle turning pacifist; a prophetic vision of crucifixion that haunted the fourth season; a Season 5 arc in which the decline of paganism and the rise of monotheism played out as a literal twilight of the Greek gods, with Xena and her new child at the center; the Xena/Ares storyline that culminated in the God of War sacrificing his godhood for love; the decline, and finally near-extinction, of the Amazons. Add to these thematic issues more graphic gore and more sexual content (by Season 6, some saw the show as veering into sexploitation), and it should be clear just how many things the various segments of the fandom had to complain about. And yet, even for the discontented, there always remained characters, settings, and plotlines to love.

NEARLY A QUARTER CENTURY after the finale, the Xena fandom has had some disappointments. While there was talk of a Xena movie in the early 2000s, which many fans hoped would bring Xena back from the dead (not an unusual occurrence in the Xenaverse), it never materialized. The fandom itself has inevitably dwindled since the show’s heyday, when there were sometimes two or three Xena conventions in a year and there was a steady stream of merchandise from photos, trading cards, and t-shirts to an annual official Xena calendar. Even so, the conventions are still happening—one was held in Burbank, California last February, the next will be in New Jersey in October 2026—and much of the show’s cast still faithfully participates, with Lawless and O’Connor always headlining.

Meanwhile, Lawless has had a successful post-Xena career, finding roles on Battlestar Galactica, Spartacus, and Parks and Recreation. She is now starring in, and executive-producing, the Australian/New Zealand comedy/drama/murder mystery series My Life Is Murder, which follows the adventures of a fearless, outspoken ex-detective and police consultant with a side hobby of sourdough baking. Some have found the character a lighter version of Xena in her funnier moments; Lawless has not made that comparison, but she describes the show as “a lot of fun,” escapism in a dark world. (She thought it was getting very dark in 2018 when the show was first conceived. Ouch.) She has also turned to directing, with the documentary Never Look Away—to be released in the United States in November—about the late New Zealand photojournalist and CNN war reporter/camerawoman Margaret Moth.

Lawless has remained strongly committed to various human rights causes, including support for migrants, since the days when she turned her gay-icon status as the star of Xena into support for gay rights long before it was a mainstream cause. She has also championed the environment, even getting arrested at an oil-ship protest in 2012; her progressive views have led to at least one online clash with former costar Kevin Sorbo; the Hercules actor is now a hardcore Trump supporter.

And Lawless is also, believe it or not, a fan of Bulwark podcasts: Imagine my surprise when, as we exchanged emails to set up an interview, Lawless wrote, “Love the Bulwark. Watch it every day on YouTube.” (She also added some praise for individual podcasters.)

At times, Lawless’s human rights activism has overlapped with her film work: She mentioned that she had agreed to do a documentary on the war in Ukraine, unfortunately put on hold because of safety concerns. And sometimes the activism, the film work, and the Xena legacy all come together: When I mentioned to Lawless that one of Ukraine’s most celebrated female soldiers, machine gunner Oksana Rubaniak—prominently featured in Bernard-Henri Lévy’s recent documentary Our War—uses the call sign “Xena,” she wasn’t at all surprised, telling me that the show “was really big in that part of the world.” (Judging by comments on Ukrainian-language Xena fan videos on YouTube, it still is.)

And so the Warrior Princess still inspires heroes, at a moment when it feels like they are more needed than ever. The line from the Xena opening credits, “A land in turmoil cried out for a hero,” sounds almost uncannily timely. And, of course, not all heroes wear swords and armor: As the show’s creator Rob Tapert put it in a promo shortly before its premiere, “Xena is the hero that we hope is within all of us.”

Yes, Lawless really did do fire-breathing, though she eventually gave it up as too dangerous; in one episode, she also had to have a bucketful of live rats thrown on her. Just another day at the office!

A particularly inventive Season 3 comedy/drama, “Been There, Done That,” mashes up Groundhog Day with Romeo and Juliet: traveling through a small town with Gabrielle and Joxer, Xena finds herself trapped in an endlessly repeating day and finally realizes that it will stop when she finds a way to save two star-crossed lovers from feuding families.

“The Price” (Season 2), which gave Gabrielle an “angel of mercy” role based on a U.S. Civil War episode in which a Confederate sergeant crossed a battlefield under fire to bring water to wounded Union men crying out for help.

Starting with early Season 1, each episode had a tongue-in-cheek “disclaimer” after the closing credits (e.g., “Xena’s uncanny ability to recover from devastating wounds was not harmed during the production of this motion picture”).

Peter Jackson was at the same time using New Zealand’s varied landscapes for principal photography for his Lord of the Rings adaptation.

Thank you for this article 🥰

It's a wonderfully refreshing escape from the trials and tribulations of today.

PS I still have my Xena T shirt, still going strong and unfaded after after all these years!

Kevin who?