Scheduling: No Triad on Thursday or Friday. The Next Level is out now, here. The Secret show will come out Friday.

1. Showing Up

When you’re a kid, social obligations don’t make sense.

Your parents say you have to go to some distant second-cousin’s funeral and all you can think is how boring it’ll be and how your life has never really intersected with these people in meaningful ways.

Then you get older and realize that it’s not about you. You understand how much it means just to show up for others.

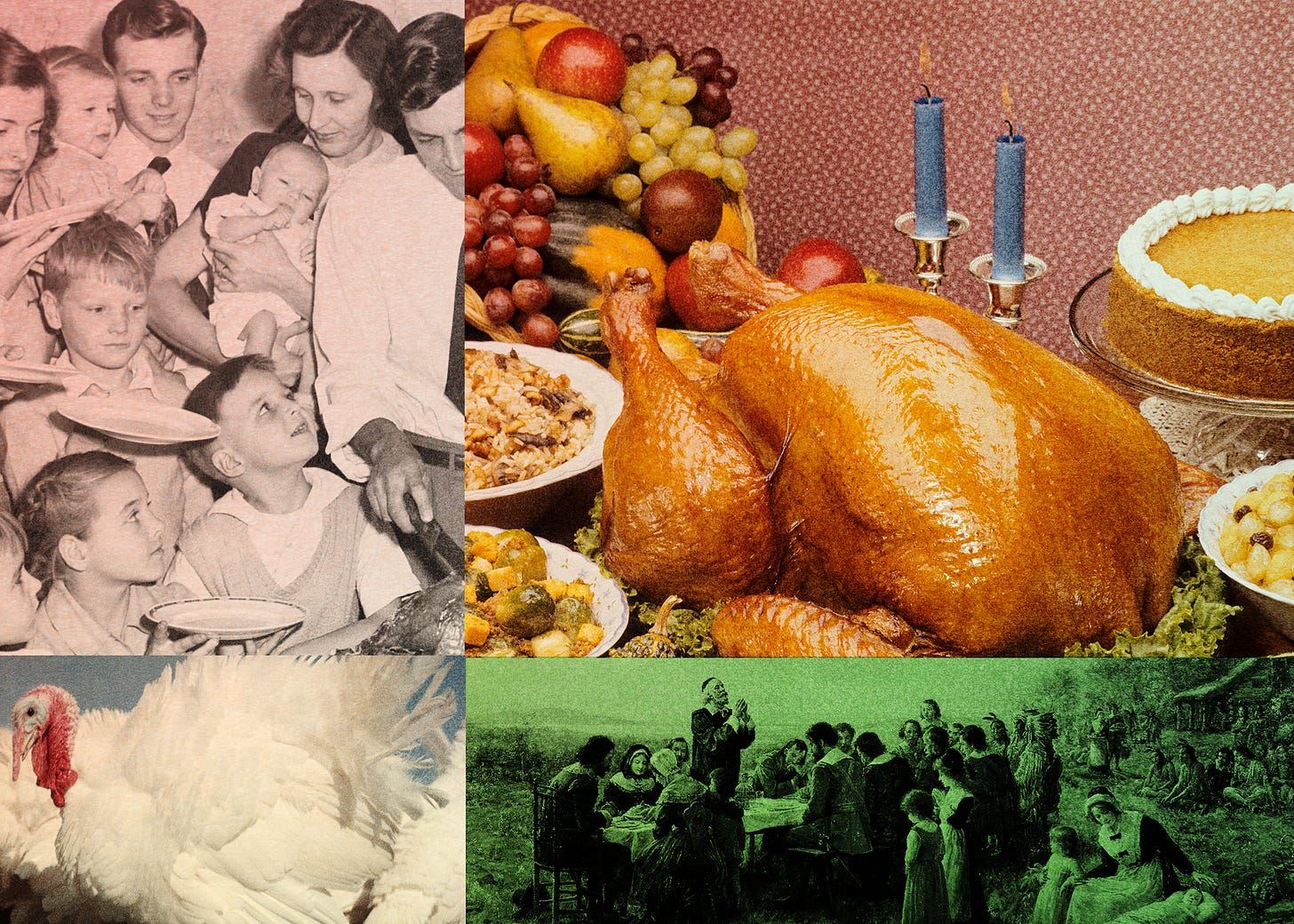

That’s what Thanksgiving has always been to me. It’s a holiday about showing up. A holiday built around the corporal acts of mercy. A holiday about being present.

You guys show up for me here pretty much every day. I can’t possibly express how much it means to me knowing that you read this newsletter. To know that if I ask your thoughts about something, hundreds of you will share them. To know that if I put out the call for someone who needs support, thousands of you will stop what you’re doing and give to them.

Writing this newsletter is a grant of enormous privilege. It has been the biggest honor of my career. I am thankful to all of you for trusting me with your time and thoughtfulness.

Other things I’m thankful for include the friendships I’ve made with so many of you. And that you guys have made it possible for us to give free memberships to anyone who wants to be part of the community but can’t swing it.

I’ve always felt a little strange having a gate here, because if you only include people who can pay, then you don’t have a community. You have a club. And I do not like clubs. But one of the things I’m proudest of—and most grateful for—is the way you’ve all pitched in so that everyone who wants to be part of this thing of ours, can be.1 No matter what. Thank you for this; it means everything to me.

2. Thankful

I’m going to talk slightly elliptically here, because I always try to balance being completely real with you against being overly personal. So please don’t take this as me being coy.

Charles Krauthammer once talked about how there is a fundamental divide in the world between sickness and health. There is the land of health, in which people have normal concerns and there is the land of sickness, in which everything is filtered through the lens of the fight to get back to health. In the land of sickness, worldly concerns become secondary while quotidian events take on extraordinary meaning.

In the land of sickness it is hard to care about, say, politics. But the question of what to cook for Thanksgiving dinner becomes enormous, because you understand that time is finite.

My family has been going through some stuff for the last month. The kind of medical and health stuff that every family goes through eventually. There’s nothing special or dramatic; it’s part of life.

Until a few days ago, the situation was fairly grim. Last Friday we got some unexpected good news and now have some very real hope. This unexpected hope, dropped into our lives just a few days before Thanksgiving, has felt like a real-deal, New Testament miracle.

I relay all this not to freak anyone out, but just by way of sharing the biggest thing I am thankful for today.

I don’t plan on talking about this again and I’d appreciate you not discussing it in the comments. But it’s what has been on my mind and my heart more than anything else and whatever my faults as a correspondent, I will always be open with you.

Happy Thanksgiving, fam. May your day be filled with love and hope.

Why Trump’s “Enemies” Keep Winning

Trump’s revenge crusade is collapsing in real time. Botched prosecutions, clown-car legal teams, foreign bot armies propping up MAGA influencers, and a GOP in full-blown identity crisis. JVL, Sarah Longwell and Tim Miller talk about Trump’s latest humiliations, the Marjorie Taylor Greene detonation, the Mamdani Oval Office shocker, and the wild bot-farm revelations shaking the right. Oh and Trump looks like he can’t walk.

3. Autobots

Harper’s has a long essay about humanoid robots. It is very much worth your time.

You can learn a surprising amount by kicking things. It’s an epistemological method you often see deployed by small children, who target furniture, pets, and their peers in the hope of answering important questions about the world. Questions like “How solid is this thing?” and “Can I knock it over?” and “If I kick it, will it kick me back?”

Kicking robots is something of a pastime among roboticists. Although the activity generates anxiety for lay observers prone to worrying about the prospect of future retribution, it also happens to be an efficient method of testing a machine’s balance. In recent years, as robots have become increasingly sophisticated, their makers have gone from kicking them to shoving them, tripping them, and even hitting them with folding chairs. It may seem gratuitous, but as with Dr. Johnson’s infamous response to Bishop Berkeley’s doctrine of immaterialism, there’s something grounding about applying the boot. It helps separate what’s real from what’s not.

All of this is going through my head in April, when I find myself face-to-face with a robot named Apollo. Apollo is a humanoid: a robot with two arms and two legs, standing five feet eight inches tall, with exposed wires, whirring motors, and a smooth plastic head resembling a mannequin’s. Like so many humanoids, Apollo exemplifies the uncanny, hyperreal nature of modern robotics, simultaneously an image from science fiction and a real, tangible machine. . . .

Apollo’s creator, the U.S. startup Apptronik, is a frontrunner in this emerging industry. The company says it’s building the first general-purpose commercial robot, a machine that will one day be able to take on any type of physical labor currently performed by humans, whether cleaning houses or assembling cars. Not knowing what to believe from what I’ve seen on social media, I’ve traveled from London to Austin, Texas, to see Apollo for myself. Against prophecies of doom and salvation, “stability testing” seems like a crude way to gauge the technology’s development, but it’s a good place to start.

As I square up to Apollo in a plexiglass arena, my first instinct is, naturally, to raise a foot. But the kick test is too dangerous for visiting journalists, I’m told. Instead, someone hands me a wooden pole with a piece of foam taped around one end and mimes poking the machine in its chest. Ah, I think, the scientific method. In front of me, as various motors rev up to speed, the robot shuffles in place, looking like an arthritic boxer readying for a fight. On the other side of the plexiglass, a group of engineers chat casually with one another and glance over at a bank of monitors. One of them gives me a thumbs-up. Have at it.

My first shove is hesitant. I’ve been told that the prototype in front of me is worth around $250,000, and while breaking it would make for a good story, it would also be the end of my visit to Apptronik. In response to my prod, the bot merely teeters. It’s heavier than I’d expected, around 160 pounds. It feels, well, like a person. “Oh, you can do it harder than that,” says an engineer, and I jab forward again. Nothing. Apollo is still trotting on the spot. Fine, I think, I’ll give it a real push. Drawing back, I grip my makeshift spear and strike the robot hard in the chest. It staggers backward, stamping its feet, flinging its arms toward me in an appealingly human gesture. I’m struck by a flash of involuntary alarm, whether out of sympathy for a fellow being or fear of an expensive accident I can’t say. For a moment, the robot looks like it might fall, then regains its balance and returns to its position in front of me. I look at its blank face with wonder and disquiet. It seems pretty real to me.

As always: If you want to be a member of Bulwark+ but can’t afford it, for whatever reason, just hit reply to this and email me. We’ll work something out.

JVL,

You may be a brilliant fellow. But mostly, you're a good man. It's the natural goodness of you and your fellow Bulwarkers that draws us (me) to you - all of you.

Love you, JVL, and our fam. So happy for your miracle.