The Oscars Head to YouTube—Just Like Everyone Else

Plus: The decline of the basic cable classic.

One of the most surprising things I’ve learned both in the course of working for The Bulwark and interviewing folks who work at ratings company Nielsen is how big YouTube is on television.

I don’t mean YouTubeTV, which is basically a cable substitute, allowing folks access to all the channels they enjoyed with Spectrum or Comcast or whatever. I mean, the number of people who watch just regular YouTube on their television. That number is shockingly high. At the very least, I was shocked when I found out that around 33 percent of Bulwark videos (as measured by hours viewed) are watched on YouTube via television. YouTube? The thing you watch on your laptop or maybe your phone? The website you pull up when you want to watch a new movie trailer or a viral news clip or something? That YouTube?

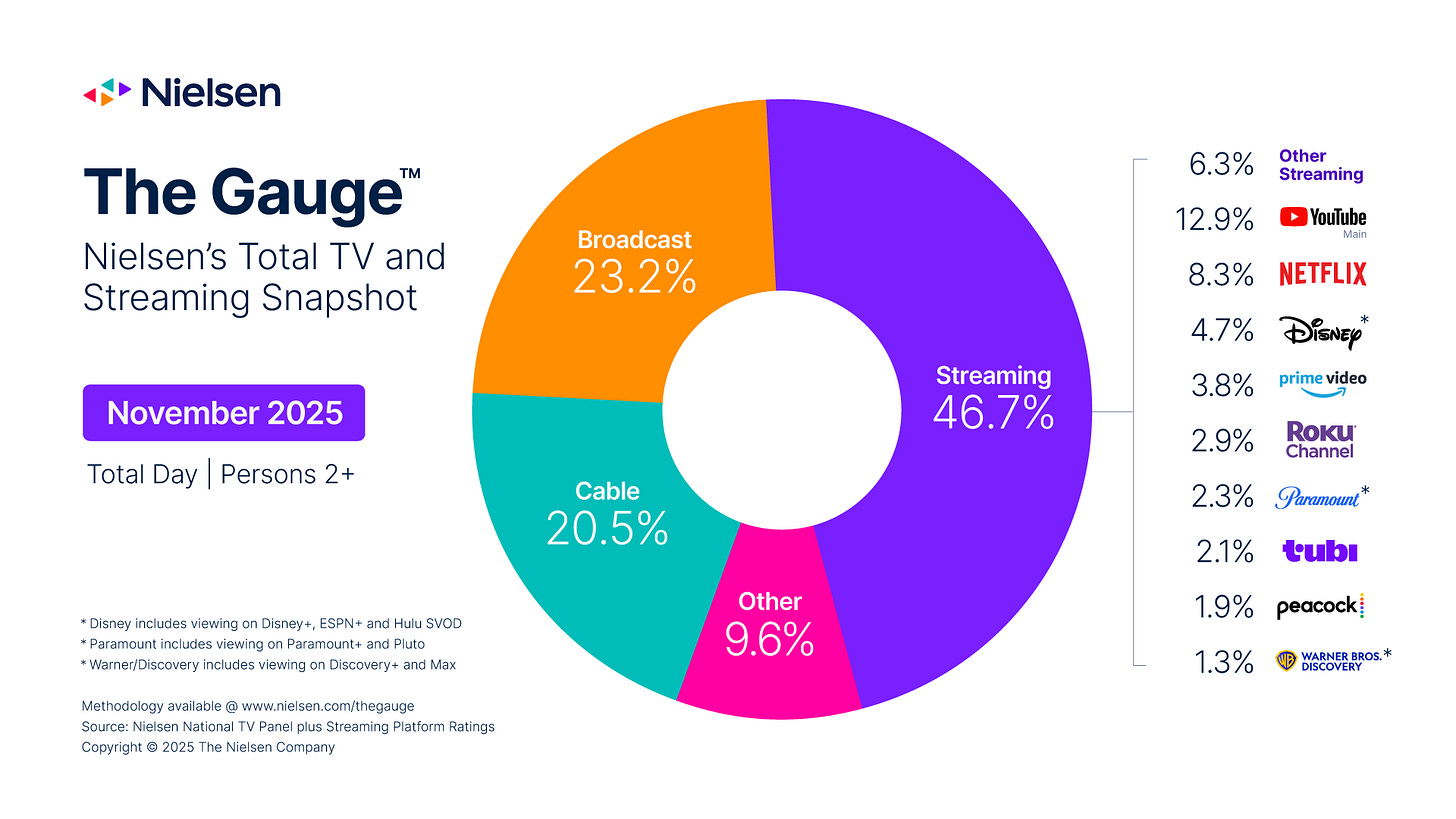

But YouTube’s increasing popularity on TV is confirmed by the folks at Nielsen every month via the Gauge, their tremendously useful measure of what’s being watched on TV. In November, 46.7 percent of all TV viewing was done via a streaming app (so, YouTube or Disney+ or Netflix, etc.). More than a quarter of that viewing came from YouTube. That means that nearly 13 percent of all time spent watching TV is spent watching YouTube—a figure more than 50 percent higher than Netflix’s and nearly three times Disney+’s (which also includes Hulu and ESPN+).

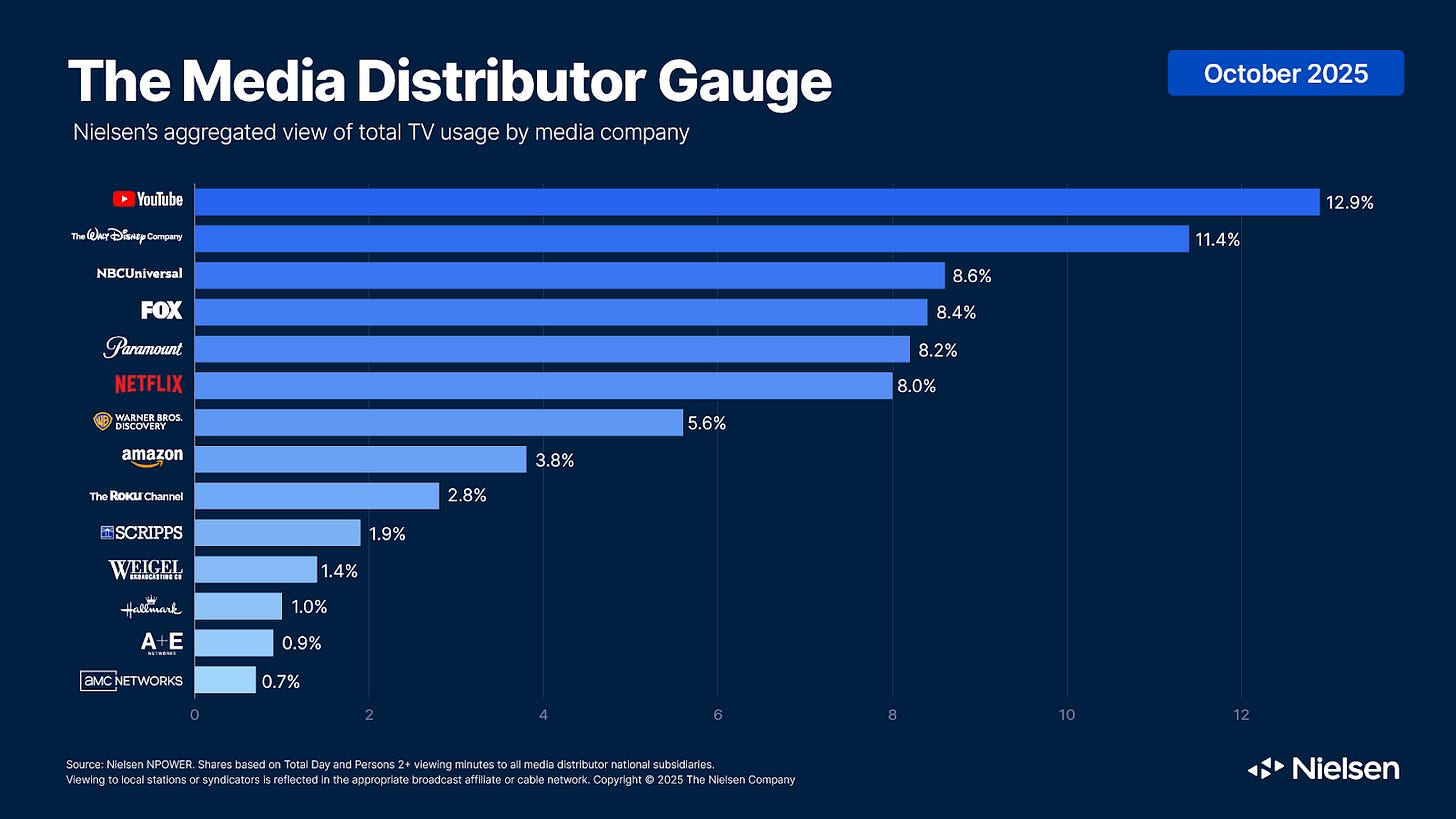

Indeed, YouTube performs better on TV than the entirety of, say, the Disney empire (which includes ABC, ESPN, etc.) or Paramount (which includes CBS, Paramount+, and a bunch of cable networks). And YouTube’s percentage does not include the hours viewed for these other services via YouTube Live. If you watch, say, TNT on YouTube Live, that gets aggregated into the Warner Bros. bucket here:

I want to lay all this out just as a way of saying that despite being a noted tech skeptic I’m not … too … upset about the Oscars jumping off of network TV and onto YouTube as of 2029. To be clear, I largely agree with David Poland that many of the supposed benefits of the show being on YouTube are, at best, vaporware. (Does anyone really want a longer Oscars?) And I’m skeptical that this will guarantee a bigger audience for the Oscars. On the one hand, we live in a streaming ecosystem in which people spend altogether too much of their brainpower making sure they have the 20 apps needed to stream the 24 shows and/or NFL games they watch in any given month. And there’s something to be said for ditching the broadcast-first format favored by ABC. But it’s still a big change, and people don’t always adapt well to big changes.

That said, YouTube, for better or worse, is, for many, just another TV channel. This is the world in which we live.

The Ankler’s Richard Rushfield hit on one of the real problems with moving the show to YouTube: It is just another symbol of the decreasing centrality of The Movies to society. Here’s Richard:

Award shows were once designed to dominate a night of television. Now they’re designed to survive inside a feed — one where relevance is negotiated minute-by-minute, not guaranteed by history or habit.

The bad news is that there are more than three channels on YouTube, and you’ve still got to give the kids something they want to see. Which — and I don’t have the data handy on this, but so I’ve been told — doesn’t tend to be three hours of below-the-line craftspeople and a handful of actors and directors thanking their agents and producers.

The issue with YouTube is the issue with modernity: the firehose of choices and the decline of the programmer.

When I was writing my obituary for Rob Reiner, I was trying to figure out precisely why that 1984-1992 run was so important, why movies like This Is Spinal Tap and Stand by Me and Misery became classics. And the answer was instantly obvious after two seconds of thought: They were definitional basic-cable classics. These were movies that played on a loop on TNT and TBS and HBO for much of the 1990s, the ten-year stretch that encompassed most of my conscious childhood.

They were good movies, yes, but they were classics because they held up on repeat viewing and you could jump in at many different points and watch the rest of the film through to the end. But they were also, simply, on. And when you had a restricted number of channels to choose from—despite a hundred options on cable, there were rarely more than ten channels that showed anything I wanted to watch—you just watched what was on when you wanted to kill some time. A programmer somewhere had decided that these were the movies everyone was going to watch and by God we were going to watch them.

So they became part of the common currency, phrases like “This one goes to 11” and “Never get involved in a land war in Asia” and “I’ll have what she’s having” became early memes, shorthand ideas, easy jokes that got an easy laugh.

Modernity has improved media consumption in key ways: we have more choice and more availability than ever before. For someone like me—someone who does not have time to just watch TV to watch TV, who needs access to a more expansive array of options than cable could ever present—that’s great. That said, I do think something is lost by the collapse of the basic-cable classic, the shared cinematic experience that disappears when anyone can start anything at any time.

The Oscars moving to YouTube (or some similar service, like Netflix) was probably inevitable, as awards shows devolve from monocultural milestones to just another niche interest. But I think it’s perfectly reasonable to at least acknowledge the symbolic decline here.

Speaking of Rob Reiner, you can listen to or watch the conversation I had about him on Monday night with Richard Rushfield, Dave Weigel, and The Bulwark’s Bill Kristol. And in today’s bonus-bonus Across the Movie Aisle (which we’ve now spun off from The Bulwark), Peter Suderman and Alyssa Rosenberg and I paid tribute to the director. Both should be free for all to watch/listen to; I hope they help bring you some measure of comfort.

Assigned Viewing: Apocalypto (Hulu, Prime Video, Peacock)

In my review of Avatar: Fire and Ash, I noted that stretches of the film (and the villainous fire clan opposed to Jake Sully and his family) call to mind Mel Gibson’s classic 2006 action-chase movie, Apocalypto. For a while, Apocalypto was nearly impossible to find on streaming or physical media, but now it’s available everywhere, so you should watch it! It’s a wild movie, pure adrenaline.

I'm going to be honest here. The quality of content on YouTube is orders of magnitude better than it is on cable television. The politics on cable TV is positively toxic. The history available is third grade analysis soaked in horrifically garbage production values and maudlin scores.

YouTube is a vastly superior platform for almost every single interest you can have. For a small fee or does not have commercials. You can easily find a two hour video on the Franco Prussian war.

Film criticism is better on YouTube. Legacy media has so massively shit the bed on quality that's it's doomed itself. It's unwatchable. There is exactly one reason to ever watch something on a network broadcast.

The New York Knicks. And even Knicks analysis is tremendously better on YouTube.

As someone who was born in 1949, I have witnessed the evolution of television from b/w to color, and from limited offerings that everyone watched at the same time to almost unlimited, asynchronous selections on multiple platforms. Movies were generally seen in a theatre vs. on TV. These days I watch very little on network TV. Like most everyone else, I subscribe to multiple streaming services, and watch what I want when I want! I always follow the Oscars, and am not bothered that they will be on YouTube. I just googled who owns YouTube and learned it was Google/Alphabet! I guess I'm mostly concerned about the monolithic corporations who control the programming!