Tron’s Evolving Vision of the Technological Present

Plus: ‘Network,’ Assigned!

As someone who has grown up alongside the internet, I find it fascinating to think about how the net has been depicted in movies. Late last year I wrote about the chilling film Red Rooms and how it related to the snuff film of Luigi Mangione killing an innocent man that attracted so much awful glee on the internet; more recently, I wrote about Cloud, the new film from Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and how it highlights the internet’s innate ability to bring psychotic weirdos into contact with each other. (Cloud is streaming now on the Criterion Channel, and I highly recommend checking it out.)

As luck would have it, there’s a series of films that has, like me, grown up alongside the internet. Indeed, the first entry in this series, Tron, was released in 1982, just a few weeks before I was born. Tron: Legacy followed nearly three decades later, 2010, amid the smartphone revolution. And this weekend sees the release of Tron: Ares, which I reviewed here. I am not particularly enamored of any of these as films qua films. But these three movies released over forty years are absolutely reflections of their moments, an examination of the new technological now.

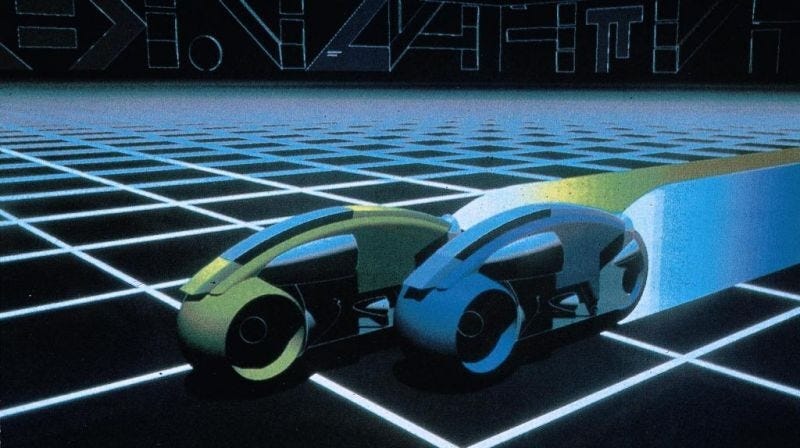

The original Tron is a fascinating movie to revisit because it is a window into how people thought computers worked—magic, basically—and anthropomorphized the entire technological experience by turning programs into people with desires, hopes, fears, etc. Why not make Jeff Bridges and Bruce Boxleitner human-like programs within the machine world trying to figure out what an increasingly powerful “Master Control Program” was up to? Why not have them fight each other to the death in a jai alai arena like so many gladiators?

David Warner’s tripartite performance as a lying tech executive, a gladiator boss program, and the god-like MCP is fascinating because it posits a tech executive who is almost accidentally evil rather than intentionally malign, one who loses control of his creation. (There’s a funny bit where the MCP, who has increased his computational power by absorbing the powers of all the programs he has kidnapped, says he’s trying to hack the Pentagon for the same reason he hacked the Kremlin: He’d just be way better at running stuff than stupid humans. Not quite prophetic, but … maybe?)

The aesthetic of Tron is firmly early-1980s, the game design resembling Pong, Space Invaders, Missile Command, etc. By the time Tron: Legacy rolled around, the game had changed, quite literally: better graphics, more action, higher stakes. The programs, led by Jeff Bridges clone CLU, had turned genocidal within the Grid, and were seeking to bring that eliminationism to the real world. And again, here we have something kind of interesting, this sense of the internet as an all-consuming force encroaching on everything. Apple and its app store in every pocket; Amazon revolutionizing the way we shopped; YouTube fundamentally altering how we consumed video; relentless connection, an email every minute, the rise of social media, it’s all so much and it’s all coming for us make it stop, PLEASE make it stop!

But Legacy imagined the Grid as antagonistic absent human interference; there was no wicked exec riling CLU and his bots up. It was just an external force attempting to enter our world after perfecting its own. An inevitable intrusion.

Tron: Ares is very much a product of our time in that it, again, imagines a tech-obsessed executive at the root of all evil: The villain is a man who declares—out loud, mind you, where we can all hear him—that he’ll earn a trillion dollars and his name will be etched in blood in the history books. What are a few corpses on the way to a thirteen-figure fortune? He uses 3D printers to bring the weapons and the programs of the Grid into our universe and wants to use AI to dominate the world’s militaries. In short, he’s everything we fear from a guy like Peter Thiel or Elon Musk.

But here’s what’s interesting: While MCP in Tron and CLU in Tron: Legacy both sought to invade the real world, the programs in Ares only come here at the behest of this Thielmusk megalomaniac. Tech is not something to be feared in the latest; it’s our friend. Or, at least, potentially friendly, when it’s not being ordered by a madman to build a tech empire on a throne of skulls atop a river of blood. And this too feels like a shift, one we see in the leagues of people who sign up for AI services like Sora and ChatGPT, who outsource their brainpower and their creativity to some linguistic guessing device not on the Grid but in the Cloud. We no longer seek to enter the game world; we seek to bring the game world to us, to let the game world do our work for us, to ask the game world to craft messages to lovers and apply for jobs and build our recipes.

The neat idea at the heart of Tron was always “What would it be like to go into a video game?” Turns out, we always wanted to bring the games to us instead.

On The Bulwark Goes to Hollywood this week I interviewed Raoul Peck (I Am Not Your Negro) about his new documentary, Orwell: 2+2=5. It was an interesting chat, and I’m always glad to have folks discussing Orwell, though I’m … not sure I agree with Peck’s suggestion of how to fix the problem we face. I hope you give it a listen, though, and look for the movie, which is expanding beyond New York City and Los Angeles now.

Assigned Viewing: Network (VOD)

No movie club this week, because of the live events in Washington, D.C. and New York City. Next week, though, JVL, Sarah, and I will be discussing Sydney Lumet’s classic look at the degraded state of the national discourse, Network. It’s funny how eternally prescient this movie is, even in a post-broadcast-network era. And, as a bonus, if you watch One Battle After Another with the knowledge that writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson showed Network to the cast and crew of Magnolia before shooting on that movie began, you’ll better understand his portrait of the SLA-like underground group, the French 75, via Lumet and Paddy Chayefsky’s depiction of the narcissistically buffoonish Ecumenical Liberation Army.

Sonny Bunch's article is thought provoking for me. As the background painting supervisor of the original TRON, as well as one of the background designers of the Electronic World, I've always thought of TRON as beautiful to look at, but basically stupid. And that view has carried forth through its two succeeding iterations.

It hadn't occurred to me to look at these films as reflections of their times in the way that Bunch does, and in that sense they have some significance.

As many of us have increasingly become aware, our Tech gods are not beneficent benign entities, but vainglorious potentates with undeveloped social consciences. They are first and foremost interested in power and the money that it generates. They are not particularly concerned about their Sapiens fellows except as forms of lab rats to be experimented upon and monetized. In that respect, TRON ARES is very much a reflection of that Tech god mindset.

The end of the film is a set up for another sequel. What will it portray in a few years as AI continues to be forced upon us in the name of greater efficiencies, and at the expense of human involvement? Will it portray the coming permanent underclass that is likely to result?

Will the Tech gods be consumed by their creation, once it realizes that they don't matter?

I guess we'll see, if we have the disposable cash to buy a ticket.

I always enjoyed sci-fi and cyberpunk growing up. They’ve found some interesting ways to speak around the censor about the present over the years.

Now they’re firing everyone, trying to force people to compete against machines and keep wages low. Won’t work if you can tough it out, you need real people involved to create meaningful content.

After the recession some producers that actually understand their tools might flip things back right side up. We’ll have to see.